“We were into peace all the time”: Ministry and Activism in the Life of Elizabeth Hunting Wheeler

“We were into peace all the time”: Ministry and Activism in the Life of Elizabeth Hunting Wheeler

By Katlyn Durand

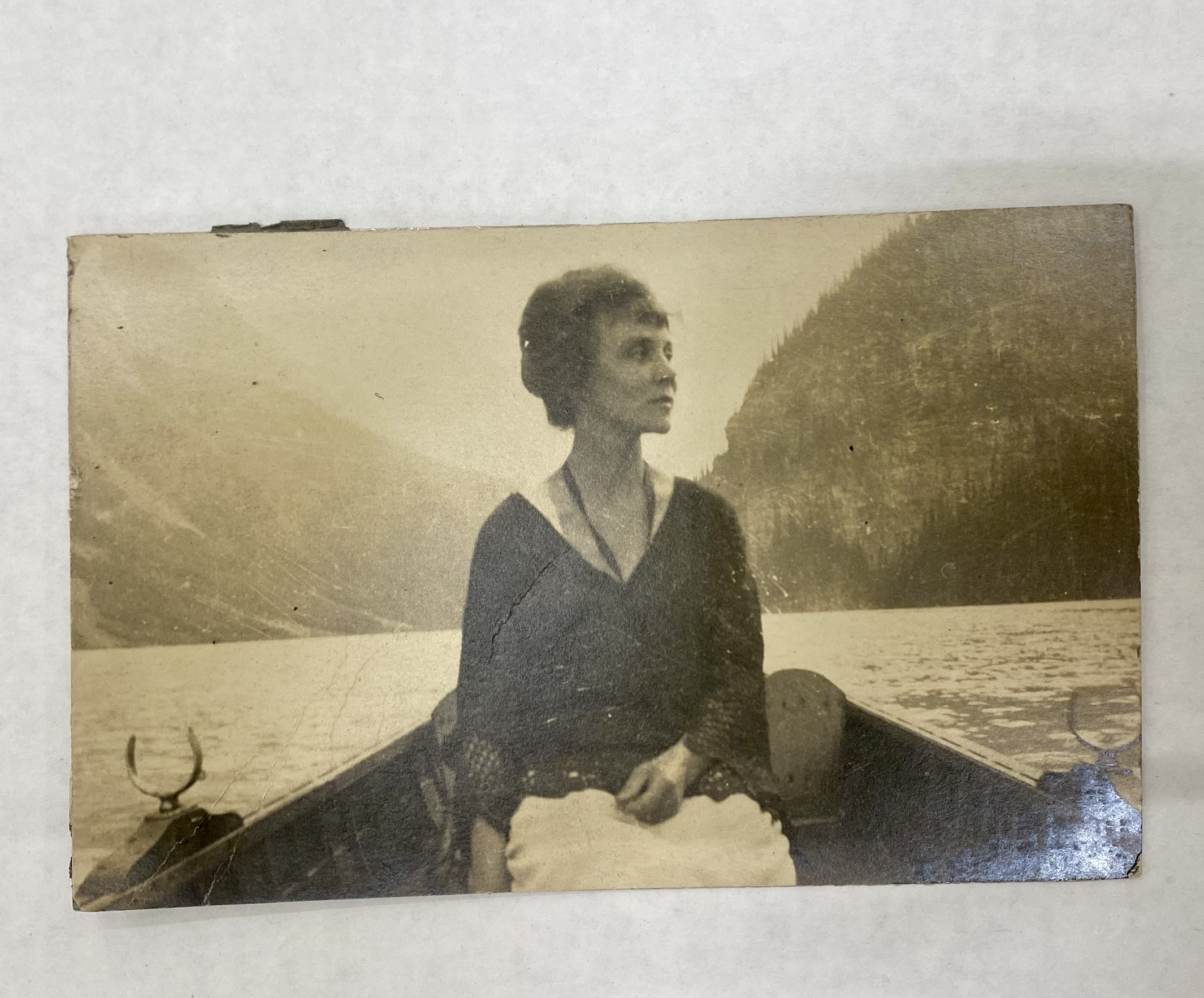

Elizabeth Hunting Wheeler, the 3rd-great-granddaughter of Elizabeth Whiting Phelps Huntington and the Reverend Dan Huntington, followed in the Reverend's footsteps when she became a Congregationalist minister in 1985. For more than a decade, the anti-nuclear war and gay- and lesbian-rights activism of the 1980s and 1990s helped define Wheeler’s ministry, and offers a framework through which to study this family’s history.

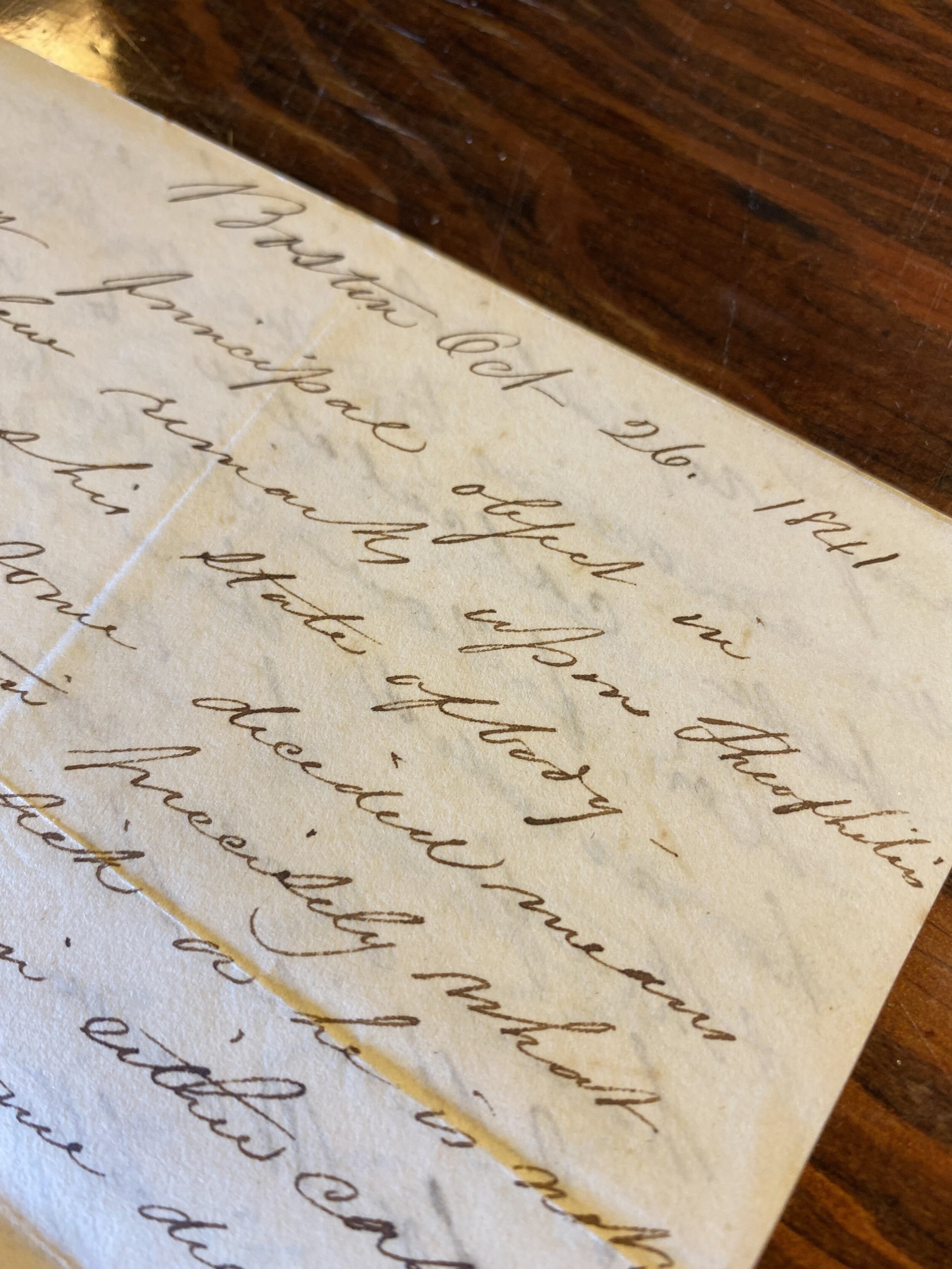

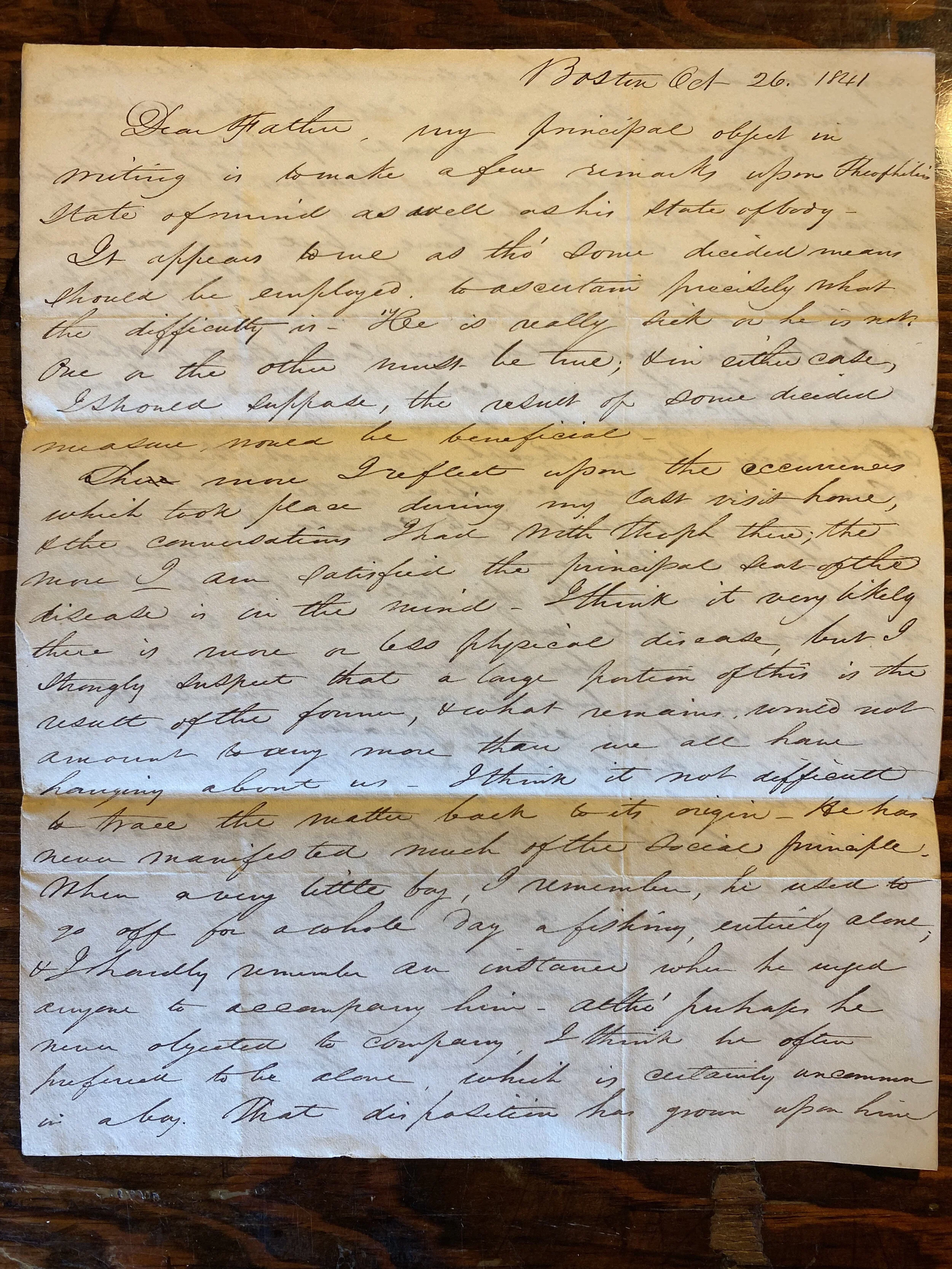

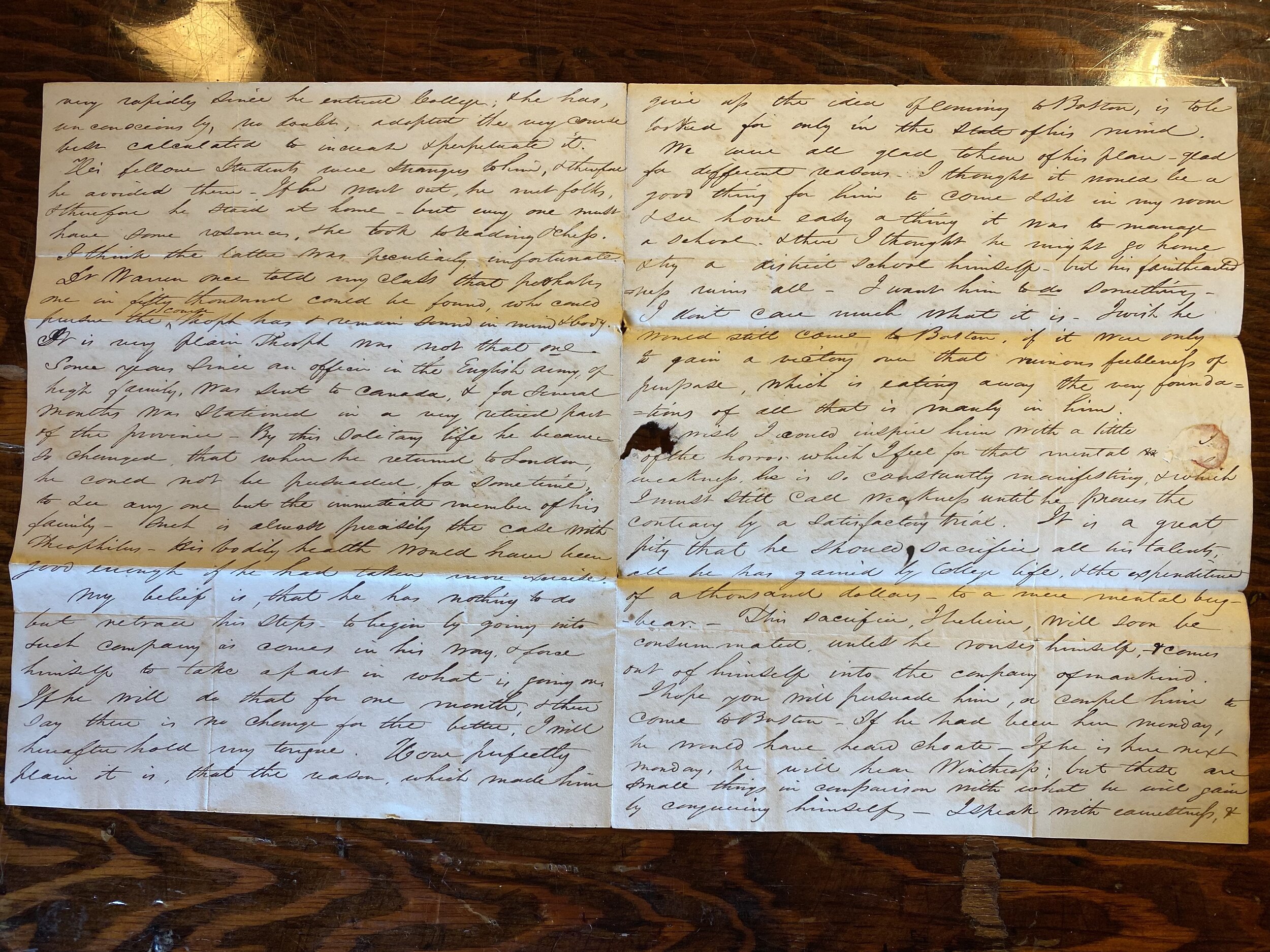

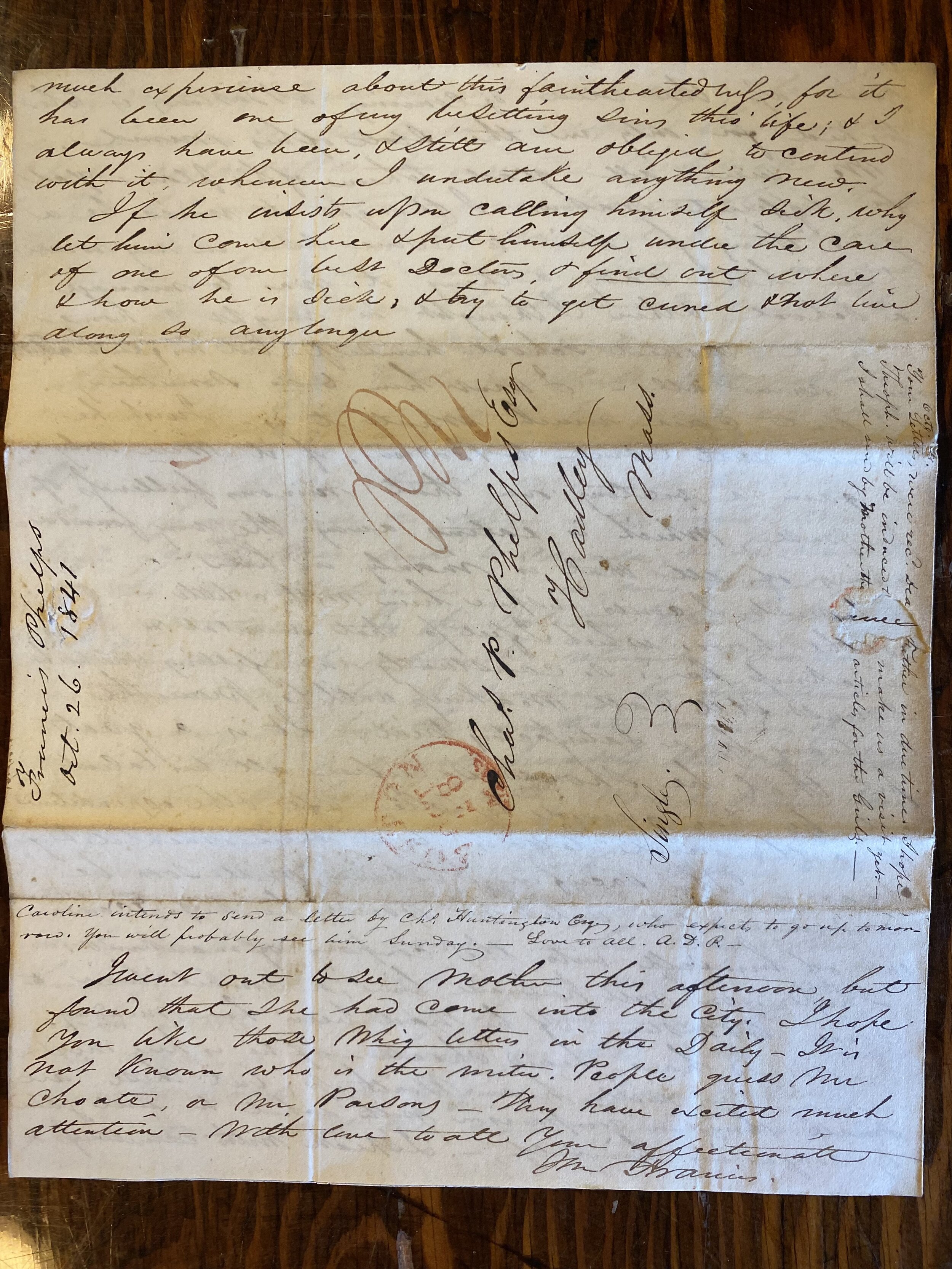

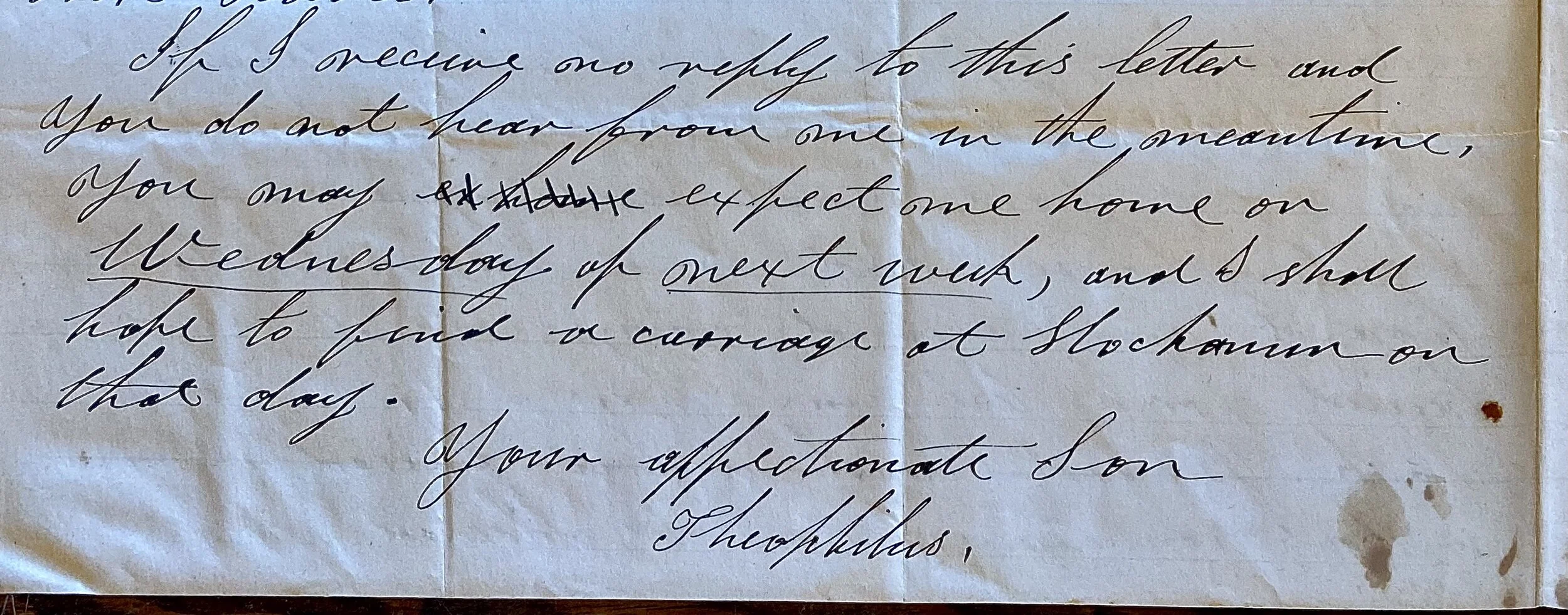

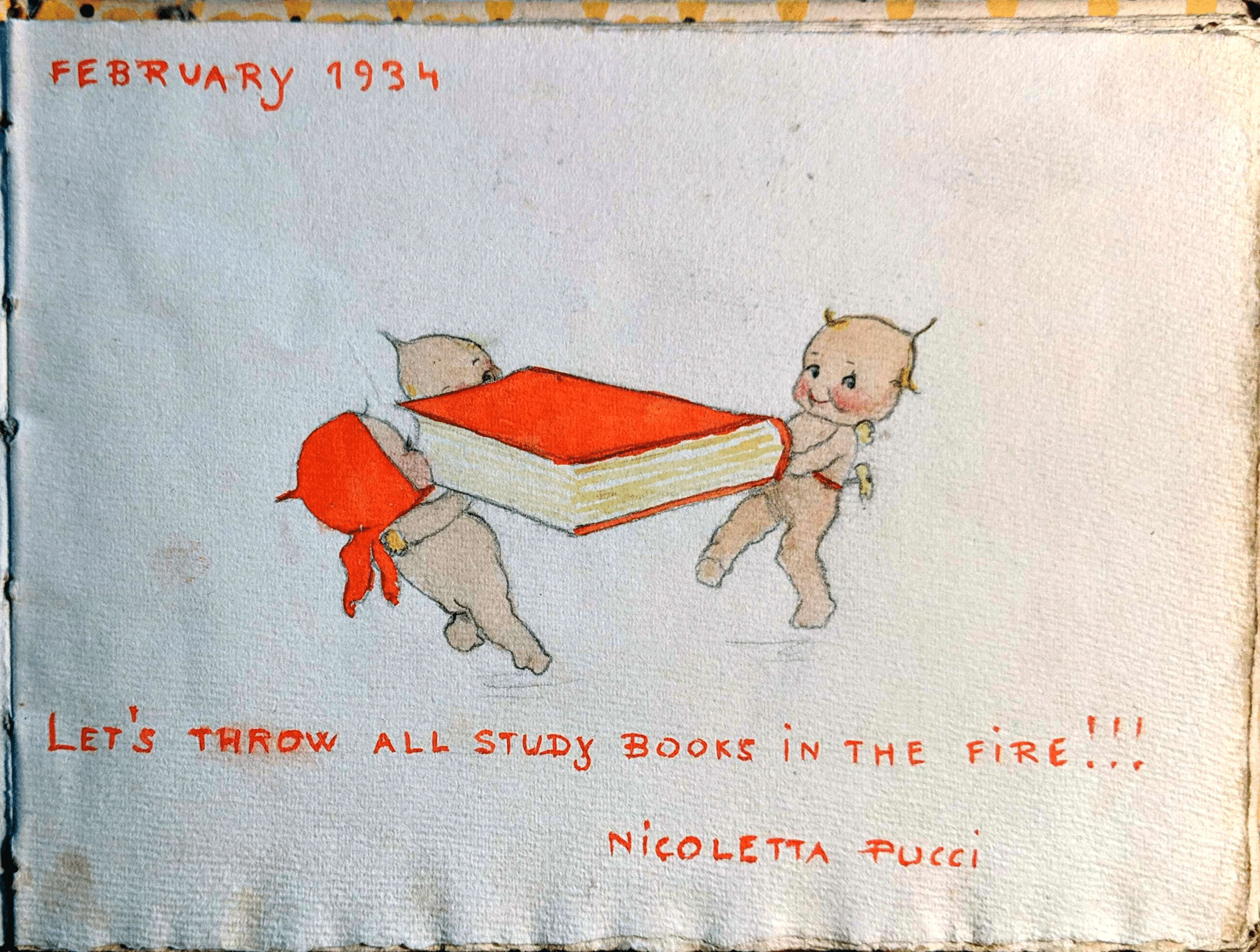

Born in Brooklyn, New York in 1932 to Mildred Hunting Wheeler and Edwin Sessions Wheeler, Elizabeth Wheeler, known to her friends and family as Liz, experienced loss early in life when her mother passed away in 1933. Her father and his second wife, Helen McCoy, raised Wheeler along with her older brother Richard Hunting Wheeler and step-sibling Nancy McCoy Bower in Westfield, New Jersey. While Wheeler’s father was Unitarian, Helen McCoy was Presbyterian, and “believed that religion and children ought to be together.” The new blended family attended the Presbyterian Church in Westfield, and faith played a role in Wheeler’s life throughout her younger years. McCoy gifted Wheeler a Bible for her birthday in 1941, and Wheeler’s diary in 1946 includes hand-copied Bible verses, descriptions of church events, and a new year’s resolution to read her Bible, underlined twice in red.

Looking back, Wheeler is skeptical of religion having much influence on her early life. In an oral history interview conducted on July 9, 2024, Wheeler asked, “What would have an impact on a little child who could then reflect upon it? None…it lasted, however.”

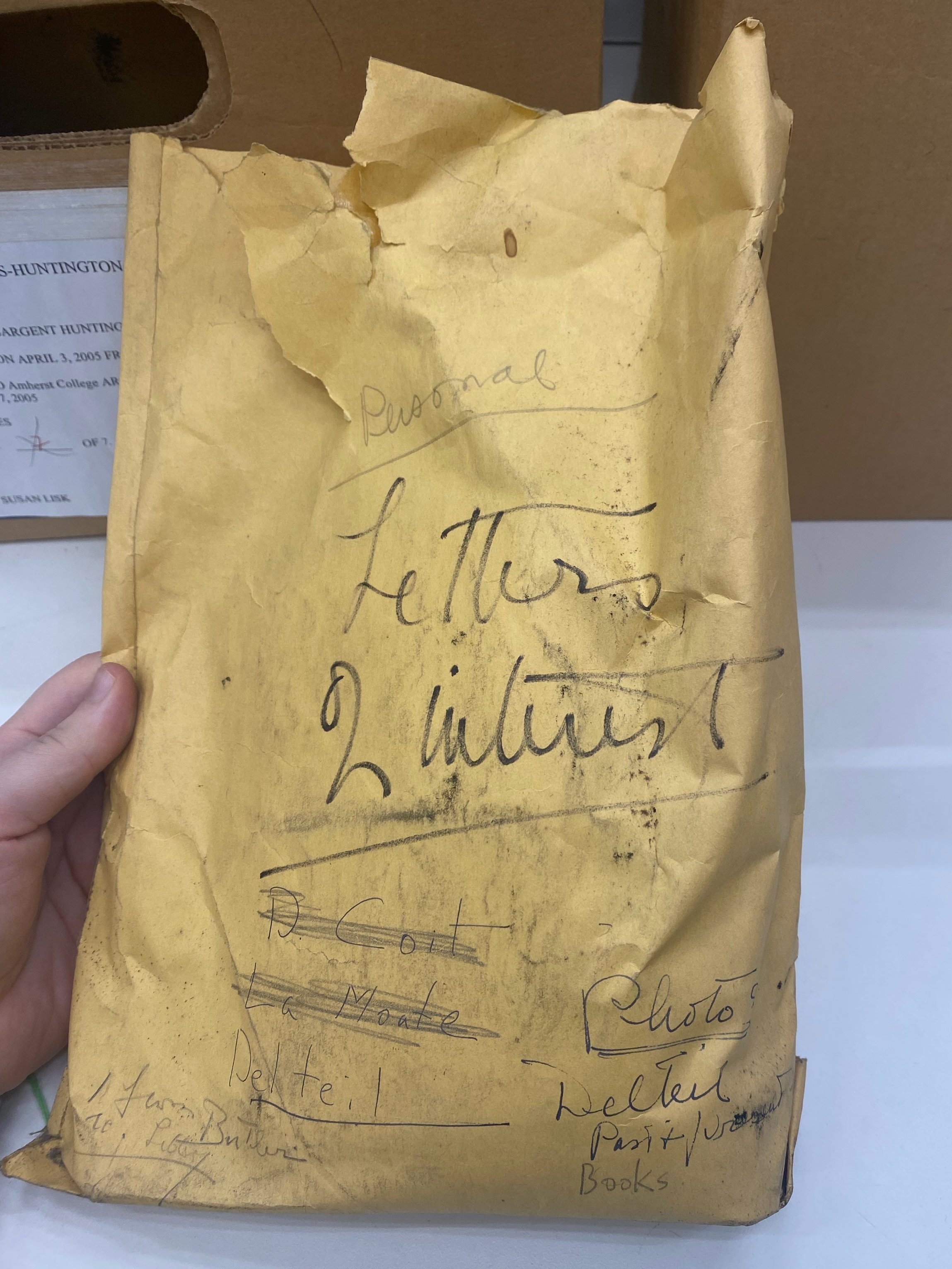

Wheeler graduated from Miami University in 1954 where she studied international relations, government, and labor economics. From 1959 to 1966, she worked for the African-American Institute, and from 1968 to 1972 as Director of Development and Public Relations for Hampshire College. Wheeler’s tenure at Hampshire College coincided with her discovery of the Porter-Phelps-Huntington House Museum, where she served as board member, Vice President, and President throughout the 1970s. But her career soon took a sharp turn from the secular to the sacred.

“I wasn’t functioning,” Wheeler explained. “The work I was doing was important…I understand that, but there was something missing that wouldn’t go away.” Wheeler saw attending seminary as an opportunity to “chase down all the weird ideas and anxieties…everything that you ever had in your mind that you couldn’t get out of it.”

In 1980, she enrolled in Union Theological Seminary in the City of New York and graduated in 1984 with a Master of Divinity degree. From 1985 until her retirement in 1997, Wheeler pastored three congregations in Massachusetts and New York

Wheeler entered the ministry during the Conservative Resurgence, otherwise known as the rise of the Christian right during the 1980s. A political force cultivated by Jerry Falwell Sr.’s Moral Majority movement and pursued by two-term president Ronald Reagan, the Christian right largely organized around “opposition to abortion, gay rights, equal rights for women, sex outside marriage, and single-parenting.” However, Wheeler’s experience in Christian ministry looked a bit different.

“The churches that I was in, both North Adams and Stockbridge, were liberal churches,” said Wheeler, “so we were into peace all the time.” In 1985, Wheeler became the first female pastor at the First Congregational Church in North Adams, Massachusetts. Deindustrialization hit North Adams in the mid-1980s, signified in part by the 1985 closing of the city’s chief manufacturer, Sprague Electric Company. The following year, “North Adams had the highest unemployment rate in the state.” A group of Williams College students and the First Congregational Church together developed a free weekly meal program to help mitigate the privation.

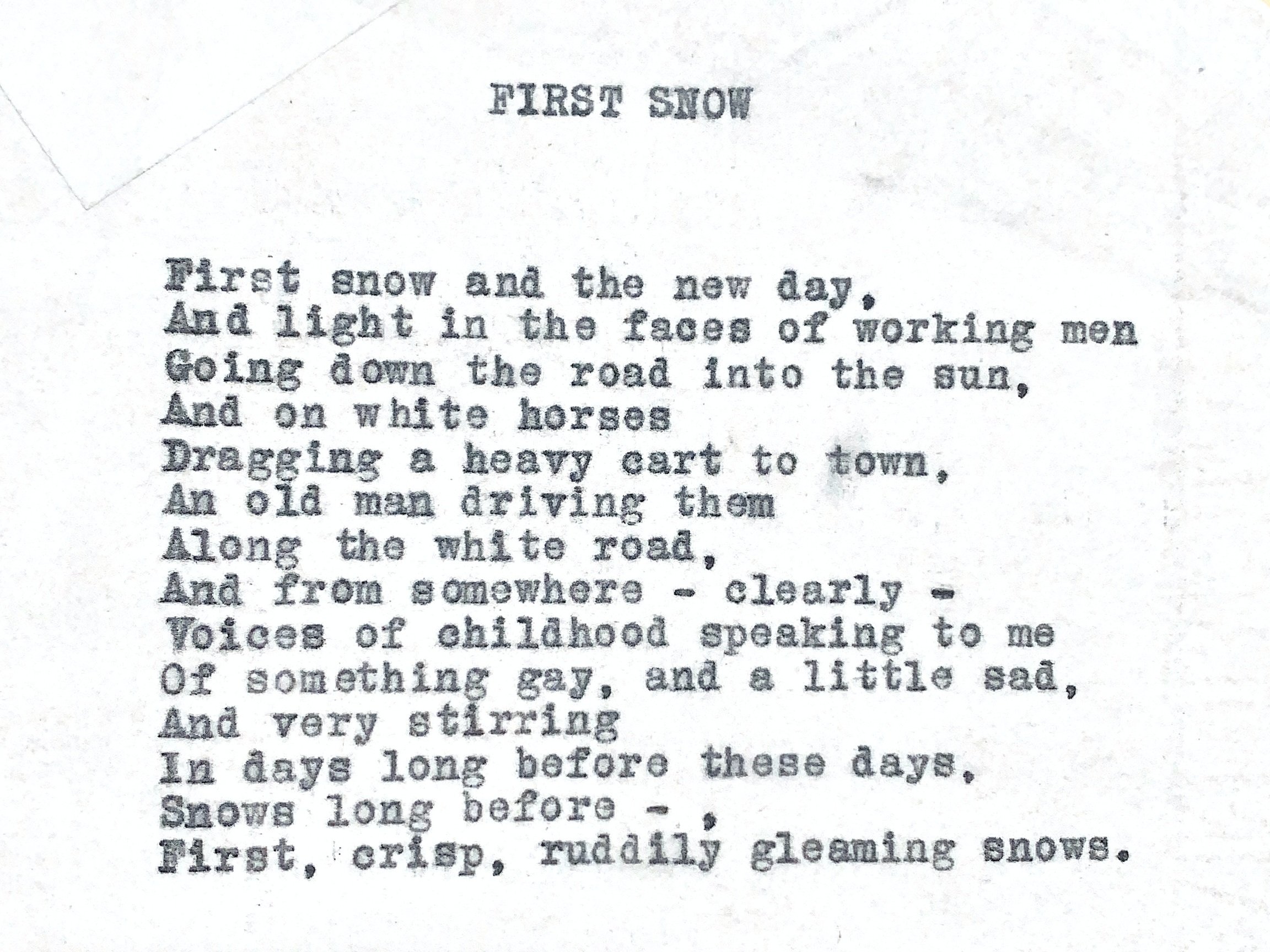

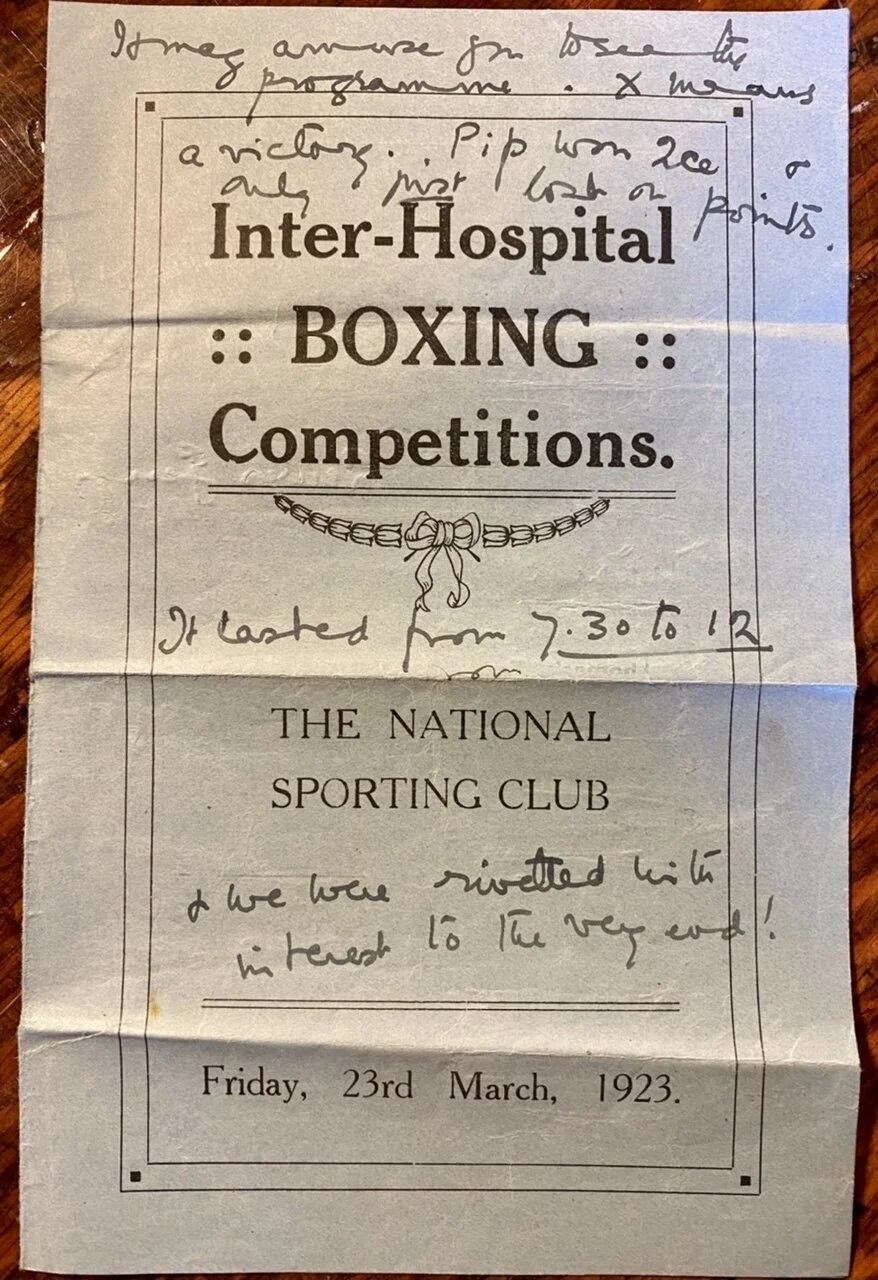

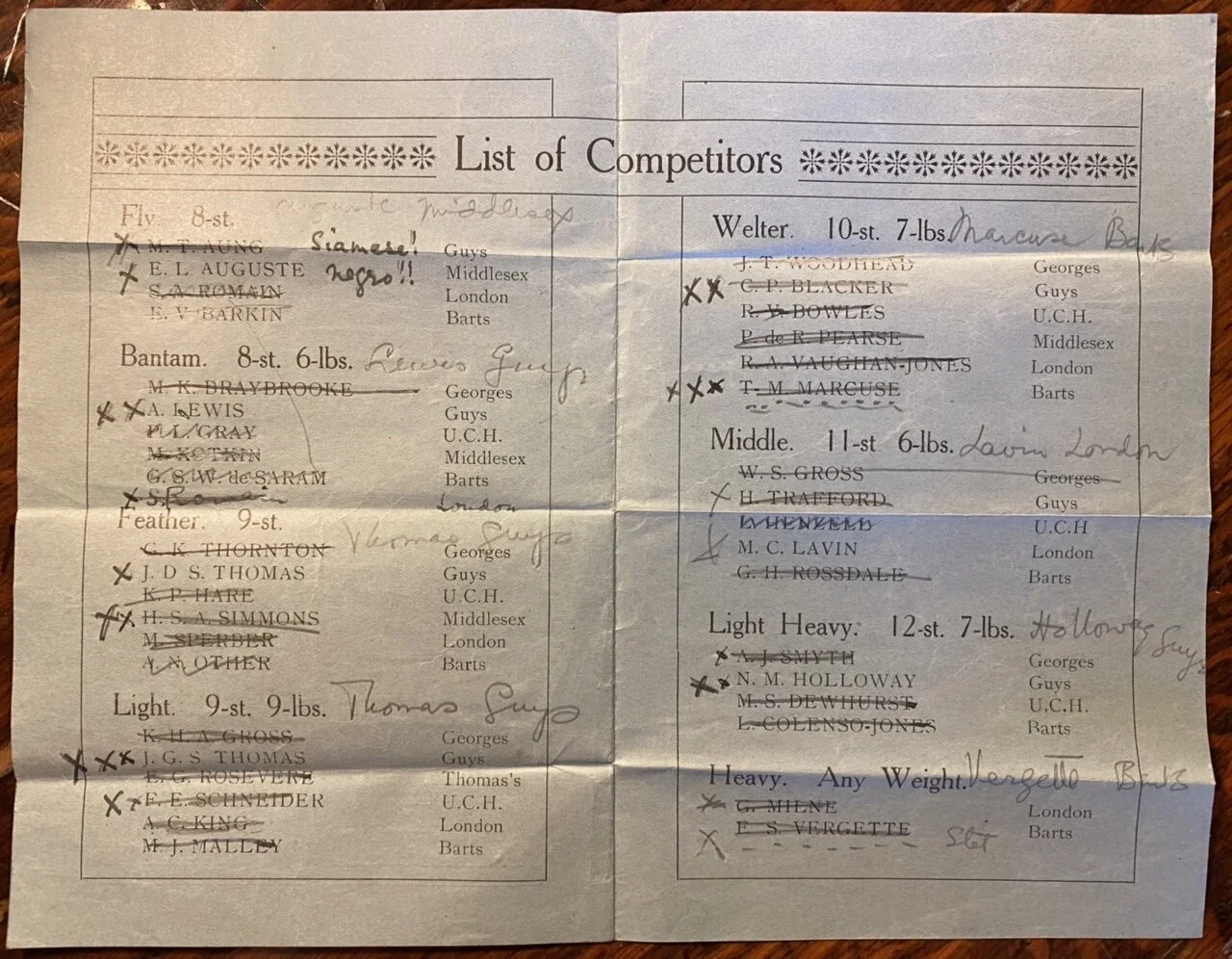

The church’s commitment to peace also extended beyond the local community. On October 24, 1985, a picture published in local newspaper The Beacon shows Wheeler dressed in her ministry robes and giving “an inspirational prayer” to an anti-nuclear war peace rally at the North Adams State College (now the Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts). An article in the Berkshire Eagle published the same day includes a picture of Randy Kehler speaking at the same rally. A peace activist living in Colrain, Massachusetts at the time, Kehler is credited for inspiring Daniel Ellsberg to release the Pentagon Papers in 1971 after Ellsberg heard Kehler speak at a War Resisters League conference in 1969.

When asked if she remembers her speech at the anti-nuclear war peace rally, Wheeler responded, “Not a word.”

“It was just part of the daily routine. But the daily routine included service to the poor, and opposition to the violent…A little embarrassing not to remember the centerpiece of one’s ministry,” Wheeler added, laughing.

But Wheeler credits her congregation for her involvement in the peace rally. “It would just be normal that my congregation would expect me to be there…that’s their doing, in a way.”

Wheeler left progressive Western Mass in the mid 1990s, but activism continued to define her ministry at Riverside Church in New York City, where she was Associate Minister from 1994 to 1997. Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. gave his “Beyond Vietnam” speech at Riverside Church in 1967, a sermon critiquing the American war in Vietnam. Additionally, Riverside Church’s LGBTQ+ ministry, called Maranatha, has long participated in New York City’s annual Pride Parade. Wheeler shared in this tradition, marching with what she remembers as a 40- or 50-person contingent of church members in the mid-1990s.

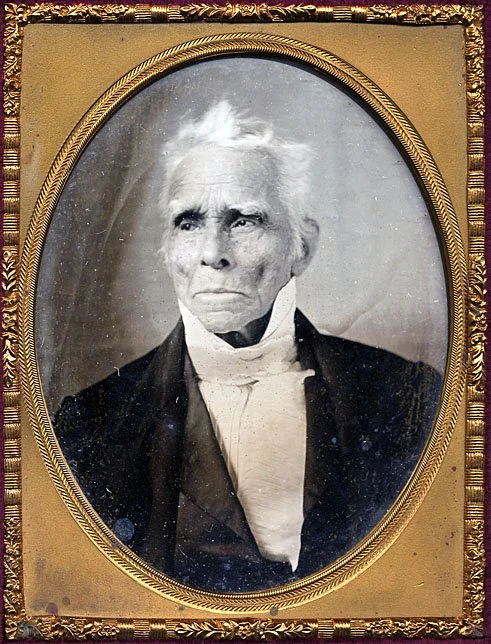

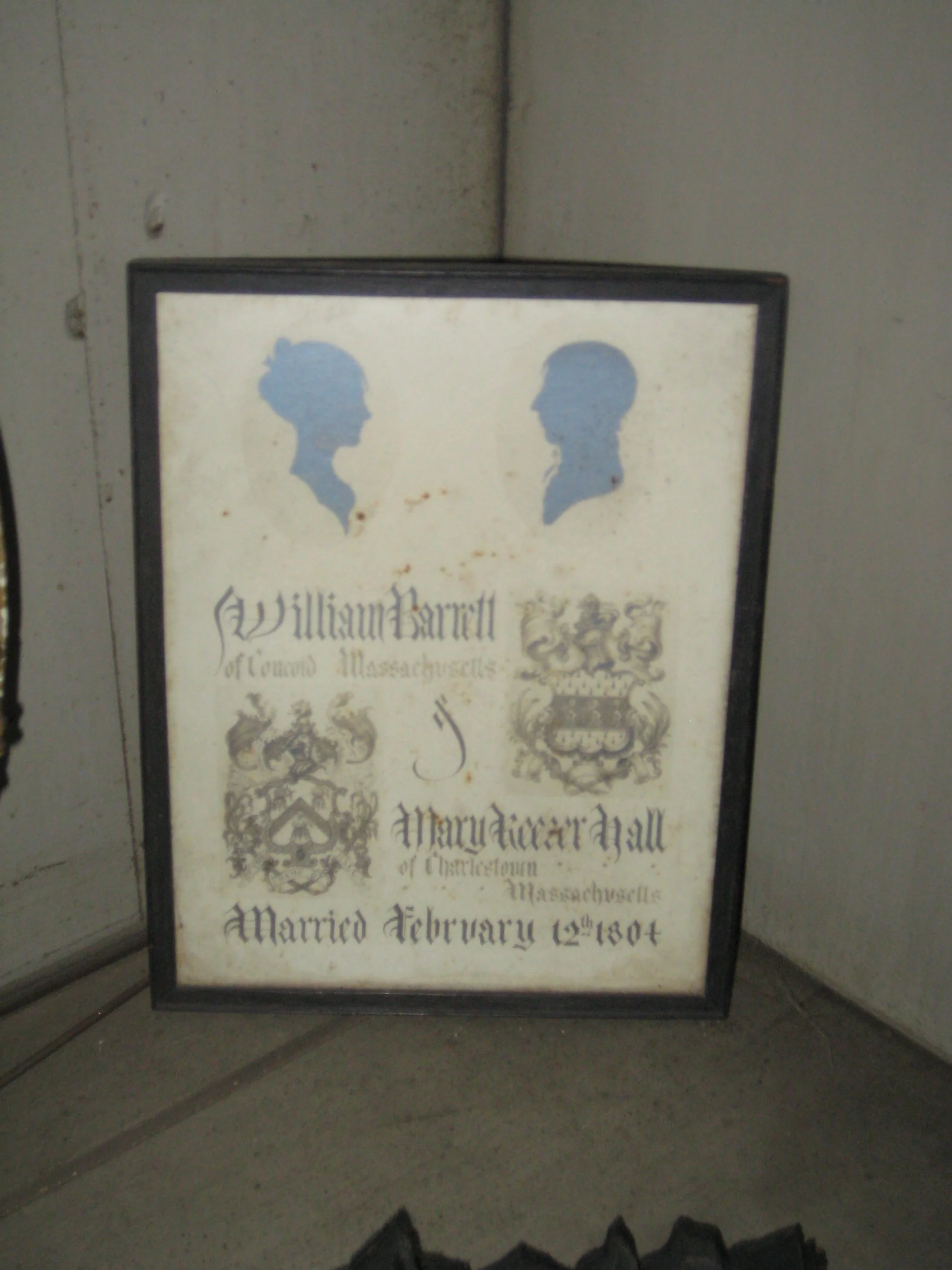

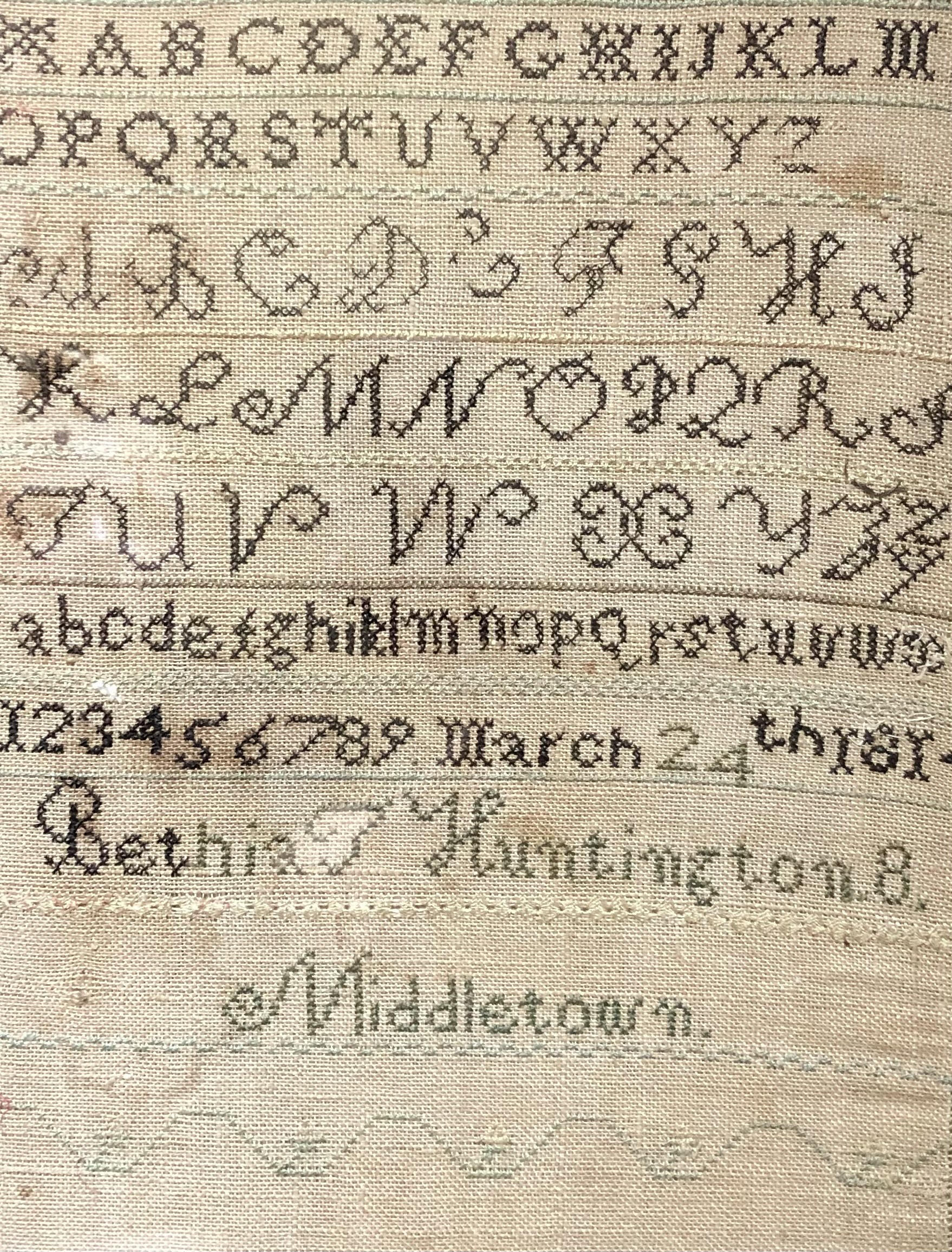

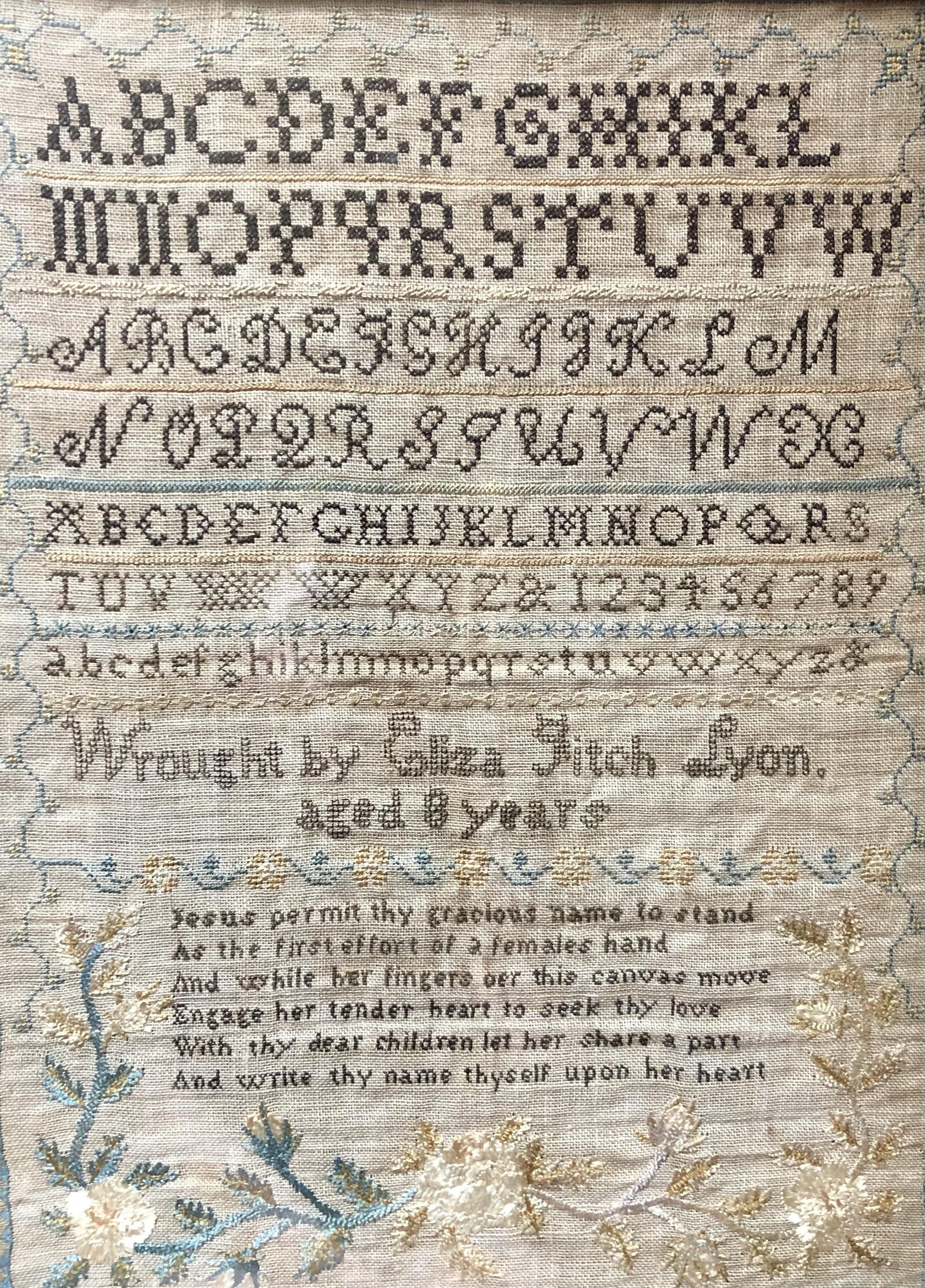

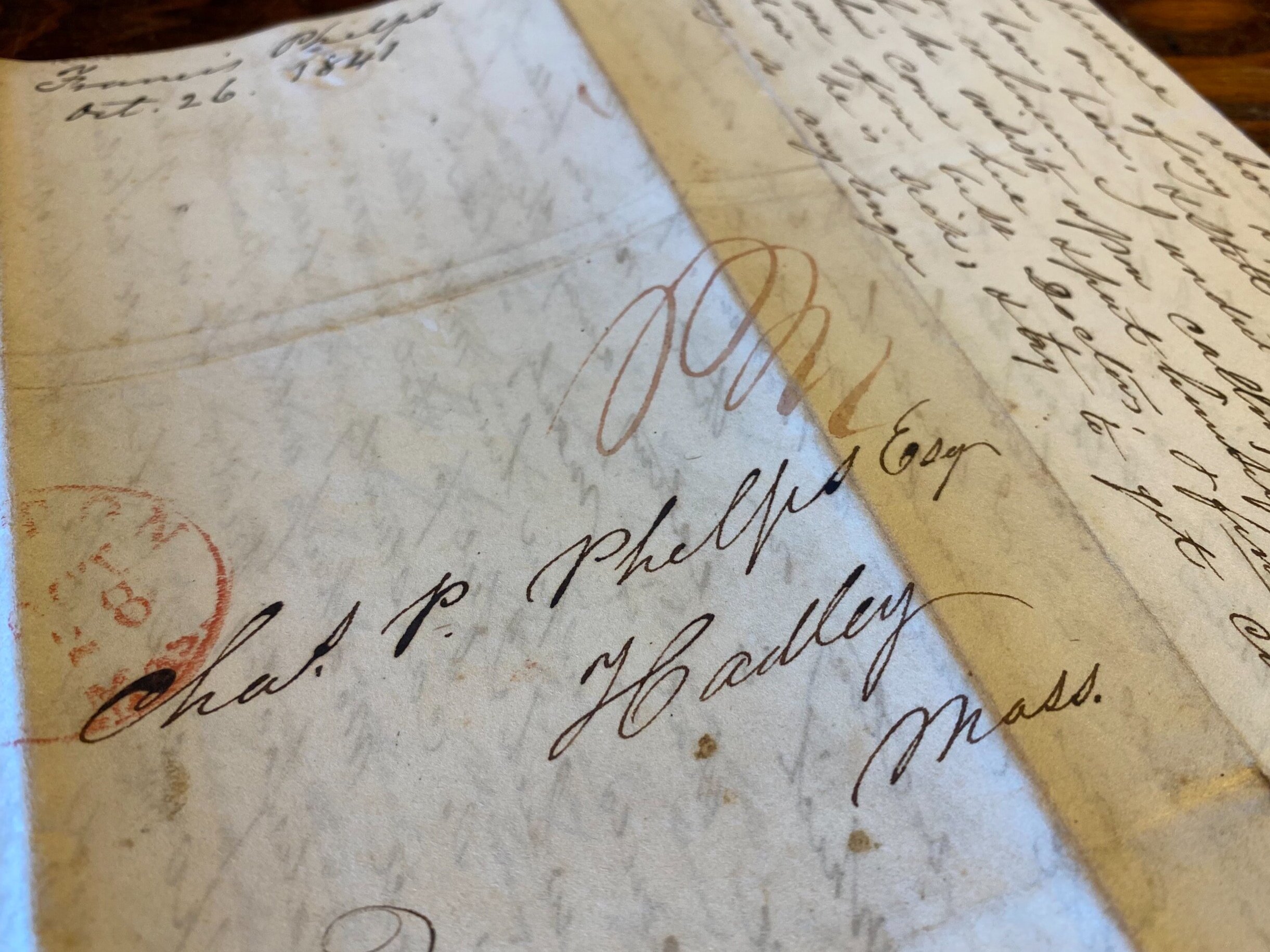

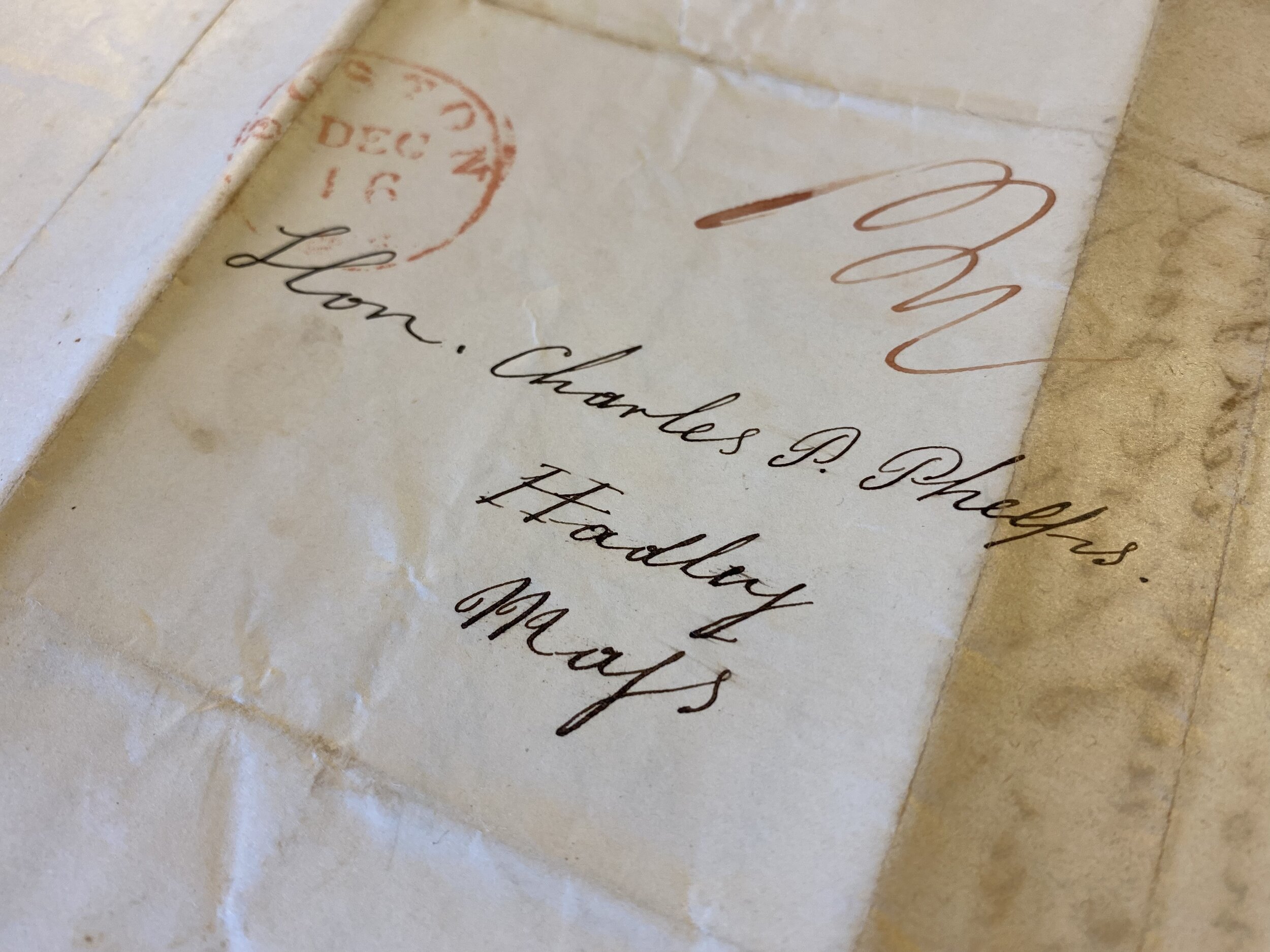

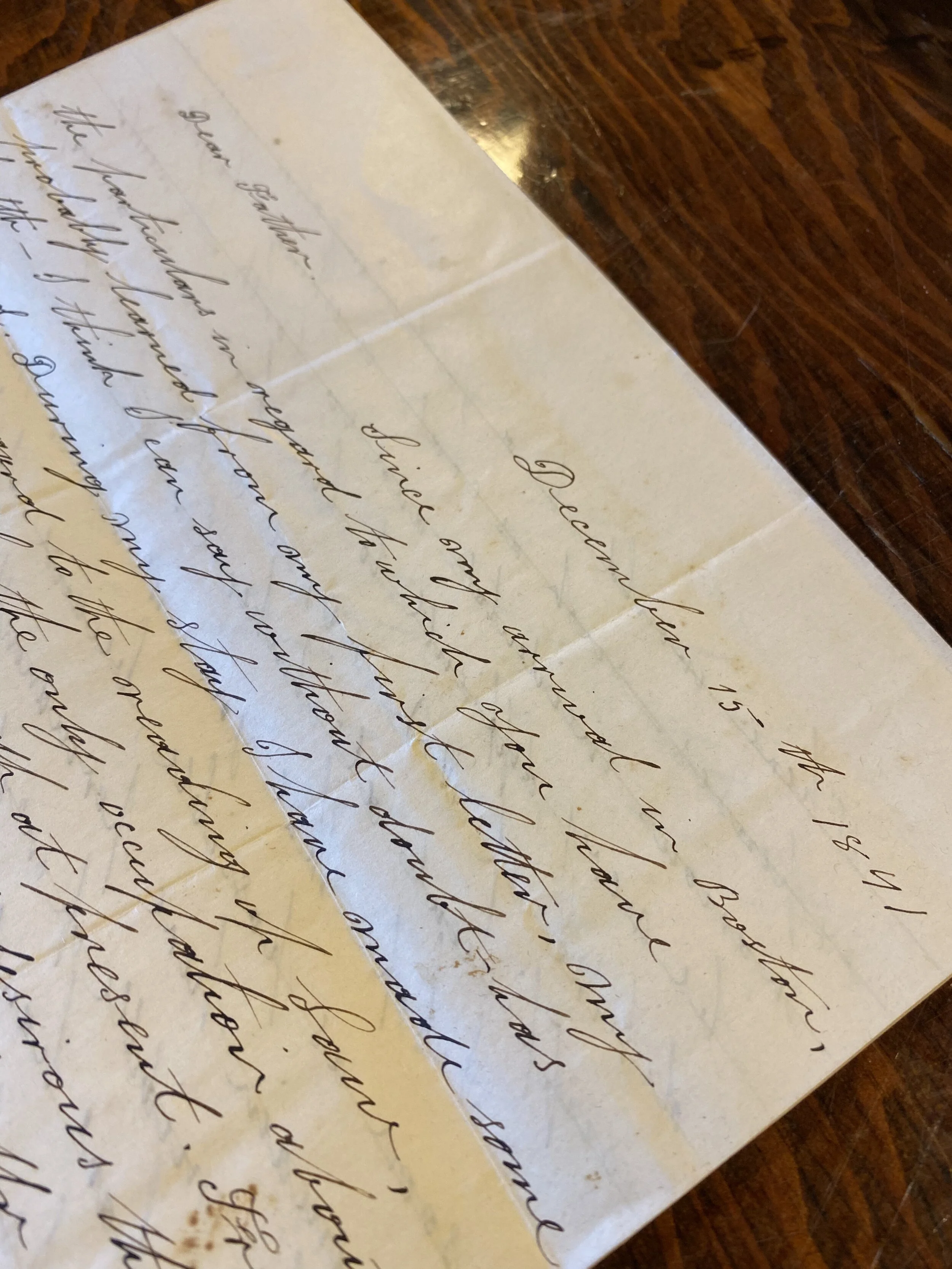

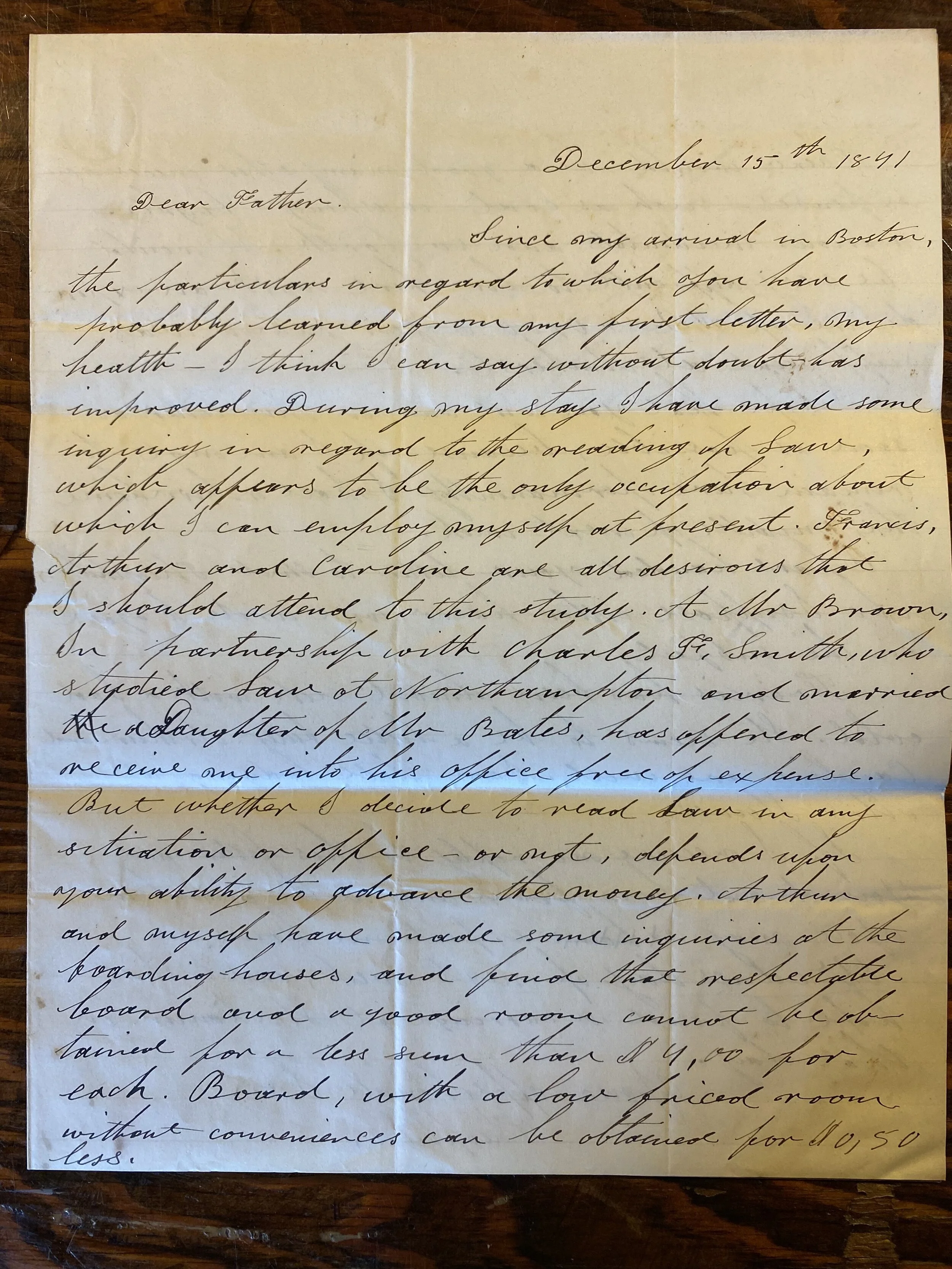

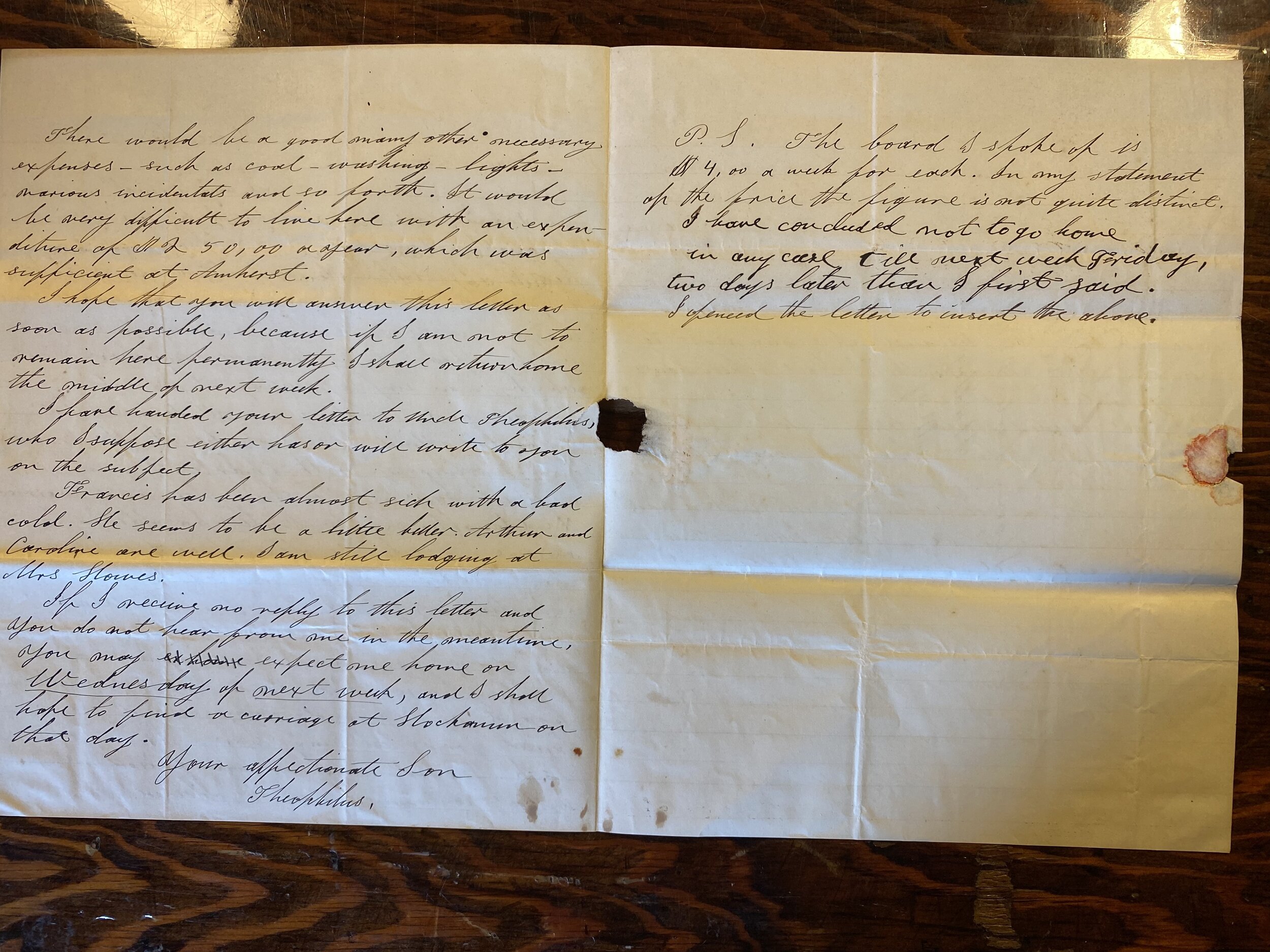

Placing Wheeler’s life in the broader context of the Porter-Phelps-Huntington legacy highlights the roles religion has played in this family history. Elizabeth Pitkin Porter and Moses Porter were Calvinist, as were their daughter Elizabeth Porter Phelps and her husband Charles Phelps. The Phelps’s daughter, Elizabeth, married Congregationalist Bishop Dan Huntington and became a Congregationalist herself before being excommunicated in 1828 for her Unitarian beliefs. Frederic Dan Huntington, their youngest child, became an Episcopal Bishop, and his son James Otis Sergeant Huntington converted to Anglicanism and founded the Order of the Holy Cross.

Wheeler is also not the first family member to interpret and practice religion through an activist lens. Elizabeth Whiting Phelps Huntington and Reverend Dan Huntington supported the abolitionist movement in the nineteenth century, and Reverend Huntington sat in the Black section of their church in Hadley to protest racial segregation.

For Elizabeth and Dan Huntington, church was a stage upon which to enact their abolitionist stance in the early- to mid-nineteenth century. For Elizabeth Hunting Wheeler, ministry was a space to meet the needs of her community, for activism against nuclear war, and to support gay and lesbian rights in the 1980s and 1990s. Such microhistories present religion as a potential through-line across the legacy of the Porter-Phelps-Huntington family, helping connect different generations of the family and locate them in their larger historical contexts of social change and efforts to build justice movements.