Sarah Phelps' Album

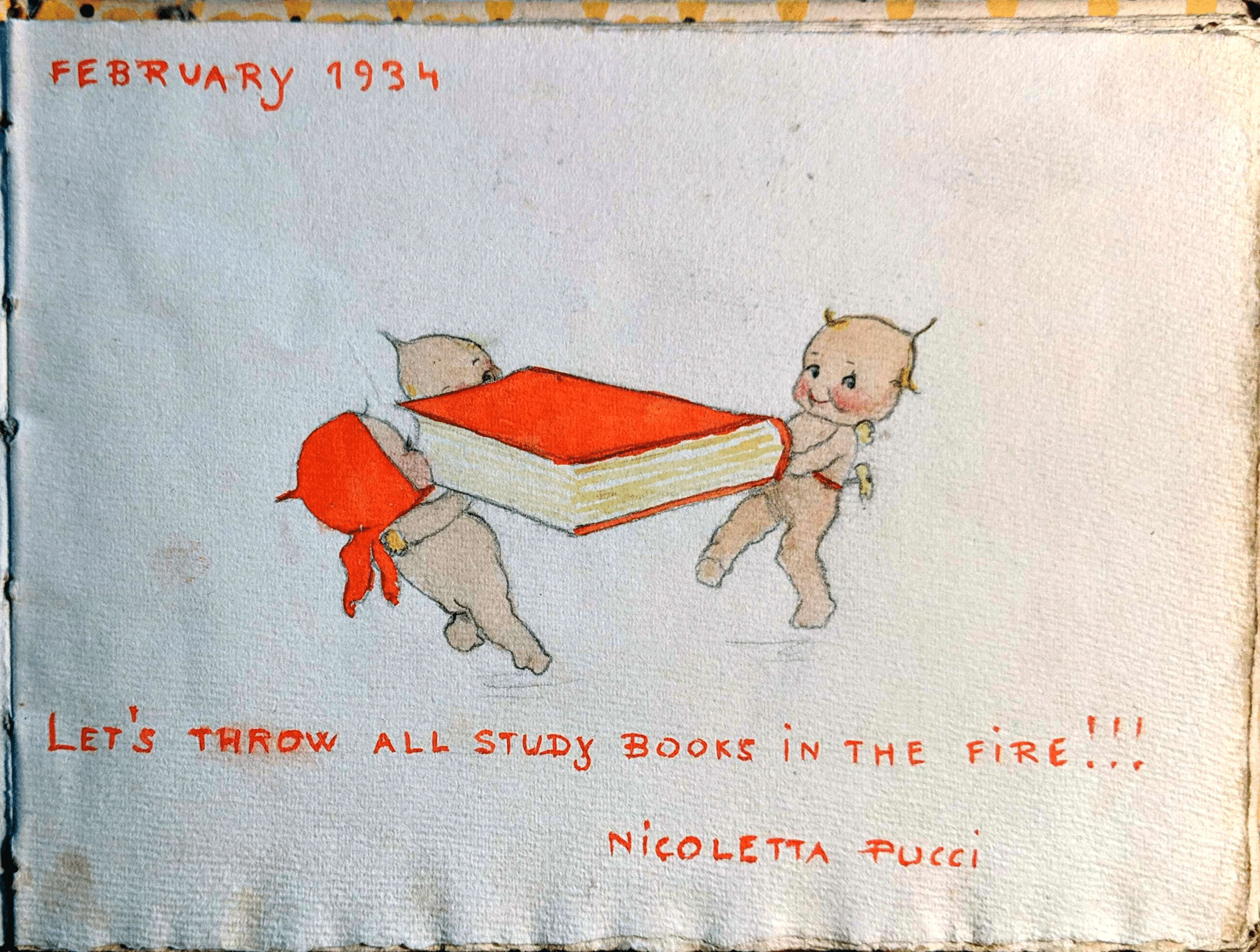

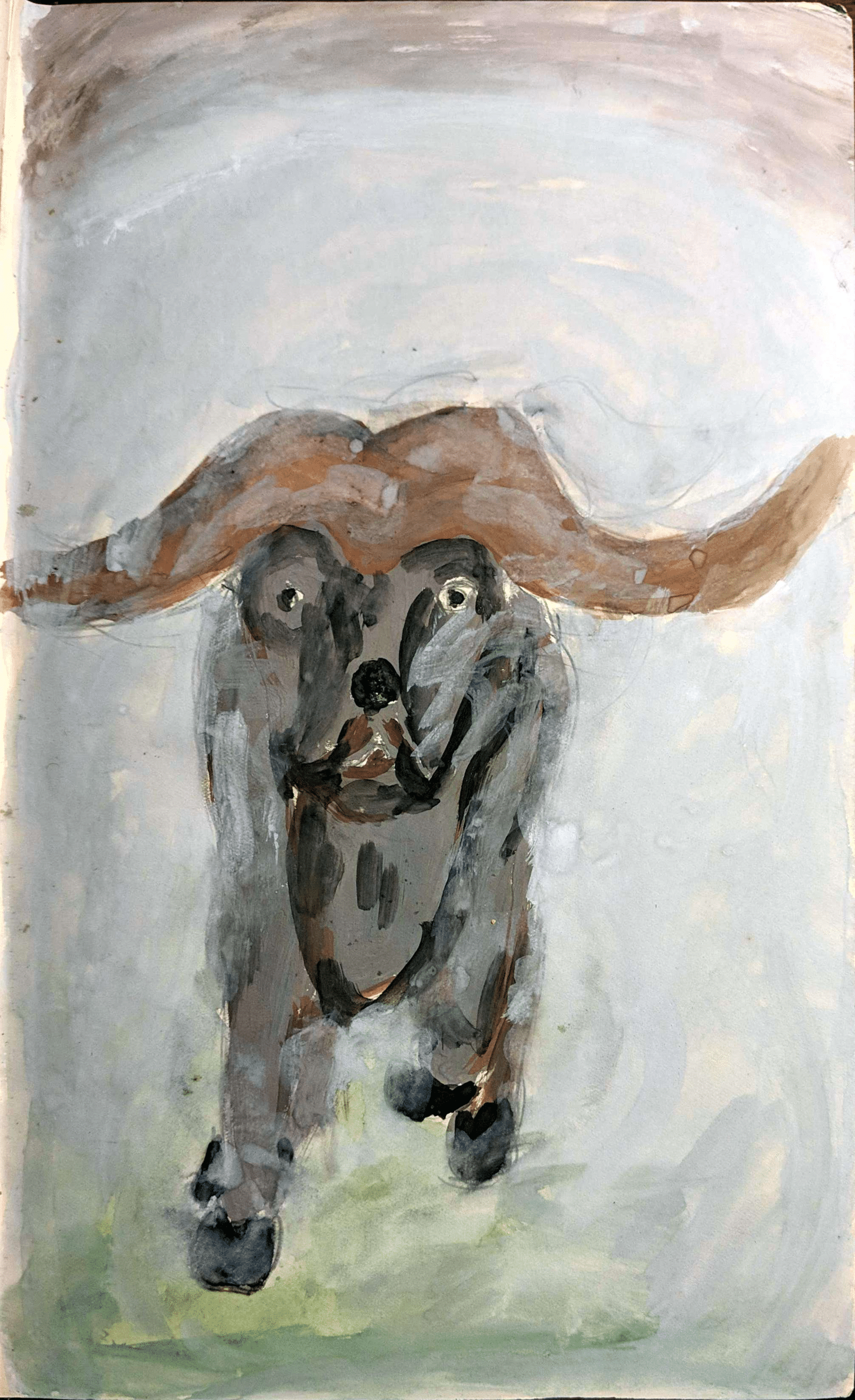

During the acquisition of Phelps Farm, the farmstead across the road from the museum that was created by Moses Charles Porter Phelps, the son of Charles Phelps and Elizabeth Porter Phelps, the PPH Museum added a number of artifacts to its collection. One of these is a scrapbook made by Sarah Phelps in 1835. This book is codex bound and filled with article cuttings from a newspaper or magazine. The articles within the album range from opinion and advice pieces to short stories and excerpts from books.

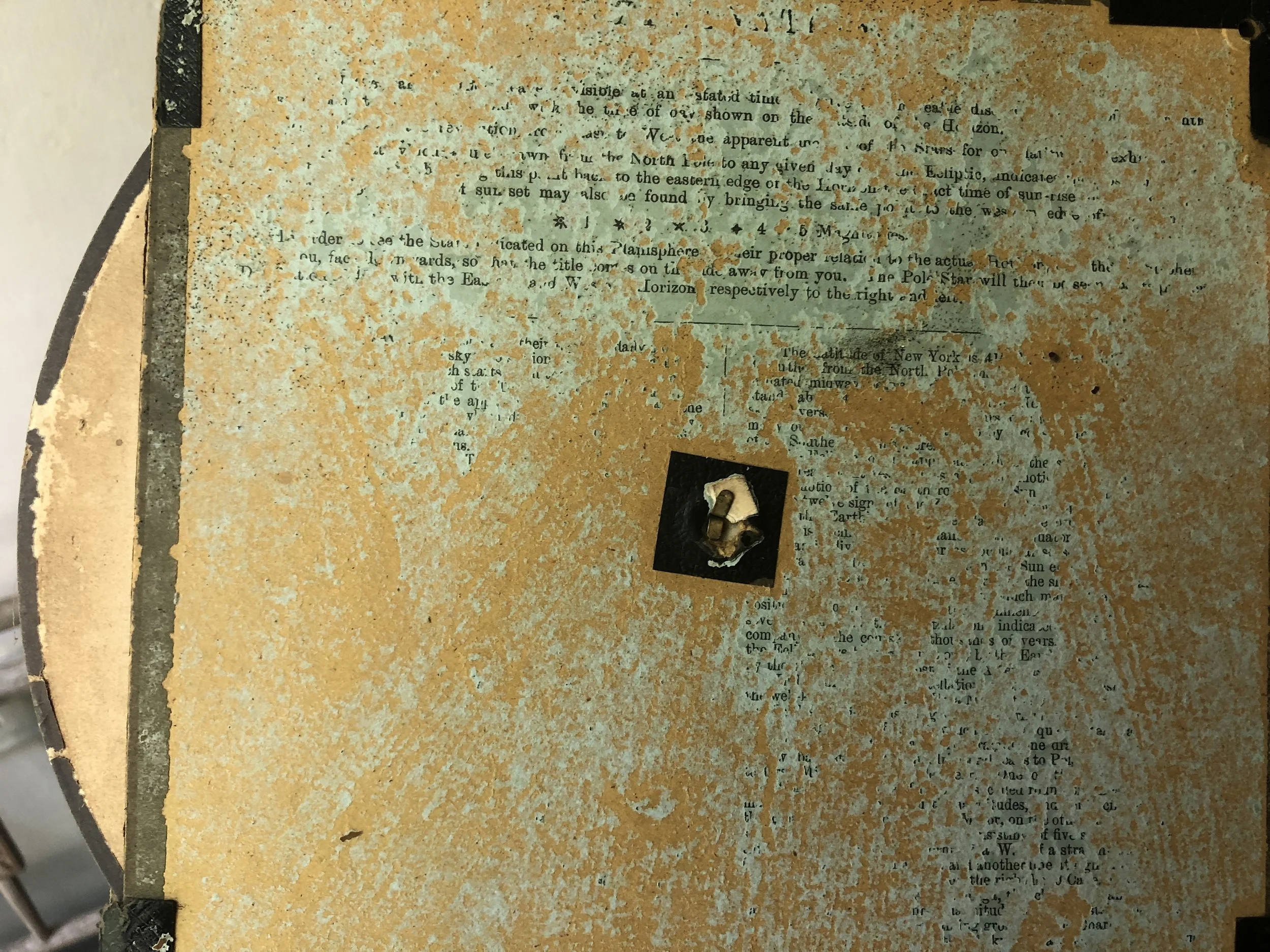

The case of the book is covered with a marbled paper that covers the case boards and the edges of the leather corner covers and spine. A number of pages have been cut out, indicating that the book was bound before the articles were pasted in and was likely purchased as an empty book. Each of the pages that was cut out is not represented in the page numbering. The spine is embossed with “Ladie’s Album, Vol. 5,” though it is unknown if this was the name given to it and separately added after Sarah had finished filling the book or if it had that title when it was purchased. The whereabouts of volumes 1-4 are unknown, if they exist at all.

Albums, and specifically ladies’ albums are a type of scrapbooking common in the 19th century.[1] Patrizia Di Bello discusses the nature of these books and their rise to popularity in her book Women’s albums and photography in Victorian England: Ladies, mothers and flirts. Part of the rise of scrapbooking was a result of technological shifts in papermaking, which made paper and other journaling supplies more accessible and affordable.[2] The articles pasted in Sarah’s album contain romantic advice and opinion columns, excerpts from books, and short stories. The articles chosen, as discussed by Patrizia Di Bello, show the nature of women’s literature and what types of stories and information were marketed to women.

After opening the marbled front cover, The first entry in the book is a hand-written alphabetical table of contents. Due to the alphabetical organization, it functions more as an index, as it is more helpful in finding a story the reader already knows the name of than it is in finding the order of the articles within. Since the articles are not arranged within the book in the order they are written in the table of contents, they were likely added day by day and the index was added once the book was filled rather than as each piece was pasted in. Further research might reveal the chronology of the book's entries, however as they are not dated it is difficult to determine this detail.

There are pressed flowers and leaves between some of the pages of the scrapbook, showing some of the continuous use of the book beyond its construction. Between pages 28 and 29, there is evidence of what was likely once a leaf that has since fallen apart. The next piece is a flower between pages 52 and 53. Between pages 68 and 69, there are a pair of evergreen (perhaps arbor-vita) sprigs. There is another flower between pages 120 and 121. There seems to be no direct connection between the plants and the articles, so it is likely that they were added as she was pasting in the articles for the day if she found an interesting flower or leaf.

Sarah Phelps (1805-unknown) was the eldest surviving daughter of Sarah Davenport Parsons Phelps and Moses Charles Porter Phelps. She was 12 years old when her family moved to Phelps Farm from Boston, and her mother died from Typhus. Her life was written about by her niece, Ruth Huntington Sessions, in “A Lady’s Reading 80 Years Ago”.[3] Throughout the article, Sarah is referred to as “Ms. Lucia”, though personal details, such as the discussion of her siblings, show that it is referring to Sarah. Ruth writes about Sarah’s love for reading, which can easily be seen in her album and the stories Sarah collected within it.

Between the mid 1700s to early 1800s, the process of European papermaking was revolutionized with the Fourdrinier machine, which used and automated the process of wove paper.[4] Wove paper is distinct from laid, or chain-and-laid paper, and named from the mesh conveyor belt that was made from woven bronze wires. The development of a flexible conveyor belt made possible long continuous sheets of paper, unlike the individual sheets made in a chain-and-laid mold. Hence, wove paper was more efficient to produce in large quantities and it quickly replaced laid paper in most uses. The pages of the book lack the distinctive chain-and-laid lines, so it is easy to assume that the book is made from wove paper.

Overall, the album is in excellent condition, and depicts ladies’ reading practices in the early-mid eighteenth century. The clipped and pasted articles within show the topics that most interested Sarah, though future efforts are needed to find the origins of some of the pieces and figuring out what magazine or paper they came from.

Notes

1. Patrizia Di Bello, Women’s Albums and Photography in Victorian England: Ladies, Mothers and Flirts (Routledge, 2017), 39-42.

2. J.N. Balston, The Whatmans and Wove (Velin) Paper : Its Invention and Development in the West, 1998.

3. Ruth Huntington Sessions, “A Lady’s Reading 80 Years Ago,” The New England Magazine 21 (October 1899): 145–53,

4. Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, "Fourdrinier machine." Encyclopedia Britannica (August 23, 2010).

Citations

Balston, J.N. The Whatmans and Wove (Velin) Paper : Its Invention and Development in the West, 1998.

Di Bello, Patrizia. Women’s albums and photography in Victorian England: Ladies, mothers and flirts. Routledge, 2017.

Easley, Alexis. “Scrapbooks and Women’s Leisure Reading Practices, 1825–60.” Nineteenth-Century Gender Studies, no. 15.2 (2019).

Sessions, Ruth Huntington. “A Lady’s Reading 80 Years Ago.” The New England Magazine 21 (October 1899): 145–53. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=njp.32101064988122&seq=155&view=1up.

Sessions, Ruth Huntington. Sixty-odd, a personal history, by Ruth Huntington sessions. Brattleboro, Vt: Stephen Daye Press, 1936.

Britannica, Editors of Encyclopaedia. "Fourdrinier machine." Encyclopedia Britannica, August 23, 2010