Sifting Through the Negatives: An Exploration of Silhouettes and Family Ties

Within the Porter-Phelps-Huntington Museum, several silhouette portraits are displayed atop mantles throughout the house. Three are kept in the ‘Long Room,’ two in the Dining Room, above the fireplaces. Two more sit in the closet within the SE Bedchamber also known as the ‘Barrett Room.’ These portraits commemorate past members of the family as well as their unique ties to the house, and help to provide a lens into the developmental history of photography, and early modes of self documentation. While the material origins of each silhouette is unknown, two signed silhouettes provide us a window into the ways in which these works were produced.

History of the Form

In the late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth centuries, silhouettes reached a peak in their popularity— the most notable period being from about 1790 until 1840, when photography was made more accessible. Before the onset of photography, silhouettes were the predecessor to this practice of remembrance around the home. This early form served to capture specific moments in a person’s life, even just through a side profile view of their face and clothing at a specific age. The earliest silhouettists began as portrait miniaturists—which were simple outlines filled with dark paint. As the silhouettists adapted to the craft and developed their artistic skills in silhouette-portraits, they began to assume different modes of production. Silhouettes vary in their procedure and resulting distinctive look; whether the pieces were achieved through ink, paper, or fabric would result in a separate classification of method. One style of silhouette creation is the ‘hollow cut’ silhouette, a paper-cutting technique which involves laying a silhouette cutout from a sheet of white paper over a black sheet of paper or fabric to create a black silhouette with a white background. This is also the most common technique used in the pieces in the museum, save for one framed piece from the family's collection.

Charles and Sarah

Kept in the ‘Long Room’ are the silhouettes of Moses ‘Charles’ Porter Phelps (1772-1857) (son of Elizabeth Porter Phelps and Charles Phelps), and his first wife, Sarah Davenport Parsons Phelps (1775-1817). They are dated to about 1800, which is when this style of portraiture was very common. At the time, Charles was a successful merchant in the port city of Boston, and the couple may have wanted to have portraits done as it was a trend of the period, especially for someone of their class.

Technique and Procedure

These beautiful silhouettes can be classified as “hollow-cut”, with the white paper being cut to the shape of Charles’ and Sarah’s bust, then placed over black paper to reveal the silhouette.

Silhouette of Moses ‘Charles’ Porter Phelps c. 1800

Although the silhouette was already cut out to reveal the shape underneath, the artist may have felt that the image did not have enough movement or detail to fully encapsulate the essence of Charles’ profile and decided to pen in more detail the texture of Charles’ hair, with ink over the white paper. This technique continues on the rendering of his shirt where William extends Charles’ chest with flounce ruffles, as well as on Charles’ face where eyelashes are highlighted.

Silhouette of Sarah Davenport Parsons Phelps c. 1800

These purposeful additions can also be seen within Sarah’s piece. Life is breathed back into the silhouette through ink embellishments that enliven and capture the naturalistic qualities of her hair and outfit. Ruffles are added to the front of her garment, as are charming stray hairs which stick out of the perfectly organized bonnet and ribbons— qualities which emphasize the femininity of her persona.

The appearance of the frame speaks to the longstanding history that the pieces carry, with tarnishing to the formerly bright shining gold frame alluding to the amount of time that they have sat within the house—-the white paper’s yellowing shares this same aging tradition of materials in these conditions. It can be imagined that the frame would have been chosen to highlight the sophisticated nature of these silhouettes, emphasizing the importance that the two profiles hold as they commemorate Charles’ time and work done in Boston. The white ovals provide contrast when laid over the reddish-orange background to add emphasis on the silhouettes and further present them in a way that draws all of the viewer’s attention to the silhouette first, preventing an interrupted sequence of attention. Instead of getting lost in the glittering gold frame or the accented red background, the onlooker is drawn first to the black silhouetted figures in the center while holding in their peripheral the significance of the silhouettes through all of the other details.

Social Context and Material Culture

Signature of William M. S. Doyle

The silhouettes of Charles and Sarah are a fascinating piece of the family’s history and provide us with more context about him as an individual and the life which he created in Boston. Both silhouettes are marked with the signature Doyle, which points to the famous silhouettist - William M. S. Doyle (1769-1828), who owned a highly successful business surrounding this trade in Boston, Massachusetts. William M. S. Doyle founded his business with Henry Williams (1787-1830), forming Williams & Doyle, who marketed themselves as being “Miniature and Portrait Painters at the Museum; where profiles are correctly cut”. With reasonable assumption, we imagine that during Charles Porter Phelps’ travels and trading done in Boston, he would have taken his wife to Doyle’s business, and brought the pieces back with them to the farmstead in Hadley, MA. As the couple lived in Boston at the time of these pieces' creation, Charles and Sarah likely brought them to the farmstead later as keepsakes from their time in the city.

Mr. and Mrs. Otis

Silhouettes of “Mrs. Otis” and “Mr. Otis”

The next set of silhouettes within the ‘Long Room’ represent a different side of the family at Forty Acres. Belonging to the wife of Frederic Dan Huntington (1819-1904), Hannah Dane Sargent (1822-1910)— who likely would have brought the silhouettes with her to the farmstead from her own family collection. The labels at the bottom of each silhouette being “Mrs. Otis” and “Mr. Otis” (depicted below) initially confused staff here, as this last name is not mentioned directly in the family tree that we use on the property. However, after digging through the Sargent family tree - Hannah’s mother’s name appears as Mary Otis Lincoln. Mary’s maiden name, living on as her middle name after her marriage, benefits the genealogies we seek to trace as we classify the portraits. We now know that these silhouettes were likely of Hannah’s grandparents on her mother’s side— the Otis family lineage. Hannah likely would have brought these silhouettes into the home to commemorate her grandparents similar to how today we hang pictures of family around our homes. Before photography, this would have been the way that family members would have been remembered around the home.

Technique and Presentation

What's particularly interesting about these silhouettes is that they are not made out of the ‘hollow-cut’ paper technique. Instead they are crafted with black paint on a white background and decorated with a bronze/gold finish on the top. This process is known as “bronzing” which came into popularity after 1800 for the ways in which it highlights details on the person being depicted without having to go through the extra work of using ink on paper after (as seen in the prior silhouettes). Black paint would have been used to foreground the individual, with gold paint being added for extra detailing. The gold also serves to add more dimension and complexity to the piece, almost lifting the figure out of the ink by providing texture to the hair and clothing that would have otherwise been left to assumption. Over time, silhouettists began to curate their craft further to incorporate this color theory to communicate texture beyond shiny inks such as gold and bronze, instead using lighter grays to achieve the same effect on the viewer.

The framing of this piece by way of the purposefully chosen solid back borders to encompass the silhouettes emphasizes the bronzing that has been done to the figures which pop out to the viewer significantly with this choice. The cohesive relationship between these elements draws the bronzing of the figures out further, creating a deeper and more complex first view of the silhouettes for the viewer. A gold background would have undermined the complexity and beautiful nature of this technique, commanding the attention of the viewer away from the carefully chosen inking done in these pieces that add complexity and depth, to that of the shining gold borders. The separation of the two pieces down the middle emphasizes that the two pieces were created separately (in the fashion of silhouette technology, they were crafted one at a time). The frame itself saves the pieces from an empty split down the middle, instead creating the effect of two separate frames in one.

Despite the age of these two silhouettes, the paper does not seem too affected by the test of time save for slight yellowing. The identification for the two figures was done in pencil at the bottom of each piece, and the fact that this is still legible to this day proves that the paper has not succumbed to the testing of time.

Fourth Generation Young Boys

Silhouette of young boy in the fourth generation (a)

In the Dining Room, two distinct silhouettes sit above the fireplace. Two profiles of young boys sit adjacent on the mantle and represent the fourth generation of the family, which includes the Bishop—Frederic Dan Huntington. This generation of 11 is headed by parents Elizabeth Whiting Phelps Huntington (1779-1847) and her husband, Dan Huntington (1774-1864). Within the limited description that is available to us through our collection—it is recorded that the two boys are brothers of Frederick Dan and that the pieces would have been created before 1815. Knowing this, the possibilities for the figureheads include brothers (listed in order) Charles, William, Edward, John, Theophilus, or Theodore. Theodore was born in 1813, which would have made it difficult for his bust to be that of the silhouette pieces, as he would have been merely 2 years old (at the latest, since we do not know the exact date of the pieces’ creation). All of the other boys were born before 1815, so this note in our archive really lends no aid as to which of the other brothers it could have been. Although we don’t know for certain their identities, their relationship to Frederick Dan is important as it situates the portraits as a part of the family tree and aids in honoring the children of this generation.

Technique and Presentation

Silhouette of young boy in the fourth generation (b)

The pieces fall under the “hollow cut” procedure similar to Charles and Sarah, yet hold none of the detail that Doyle brings into their depiction through later-added ink. They are simply cut white-paper overlay silhouettes of the young boys, framed with silver and gold foil—which add emphasis on the centered busts. The aligned gold stars on each corner of the frame draw the viewer’s eye to the center of the piece, which is surrounded by silver foil to point all attention to the silhouette. Although all of the adjourning details within the frame are beautiful on their own, they are used as a tool to make sure that the viewer knows exactly where they are meant to be looking within the piece. It can also be theorized that the foils and frame were added to create a ‘high-class’ feeling to the otherwise plain silhouette, considering that the aforementioned style of these silhouettes are “hollow-cut” and do not have any detailing to liven the piece otherwise. The frame and shine of the silver and gold make the piece feel expensive, as well as more important - less likely to be ignored.

Barrett Room Collection

While the other silhouettes within the home sit atop the mantles throughout the house, the silhouettes found in the ‘Barrett Room’ or SE Bedchamber were harder to notice, as they sit within the dimly lit closet which is propped open when tours are given. As there is so much art and historical significance within the Barrett Room decorating the walls, it is easy to get lost before visitor’s even think to look within the closet. However, these pieces serve as historical context for silhouettes as they provide a different use for the profiles rather than just self documentation.

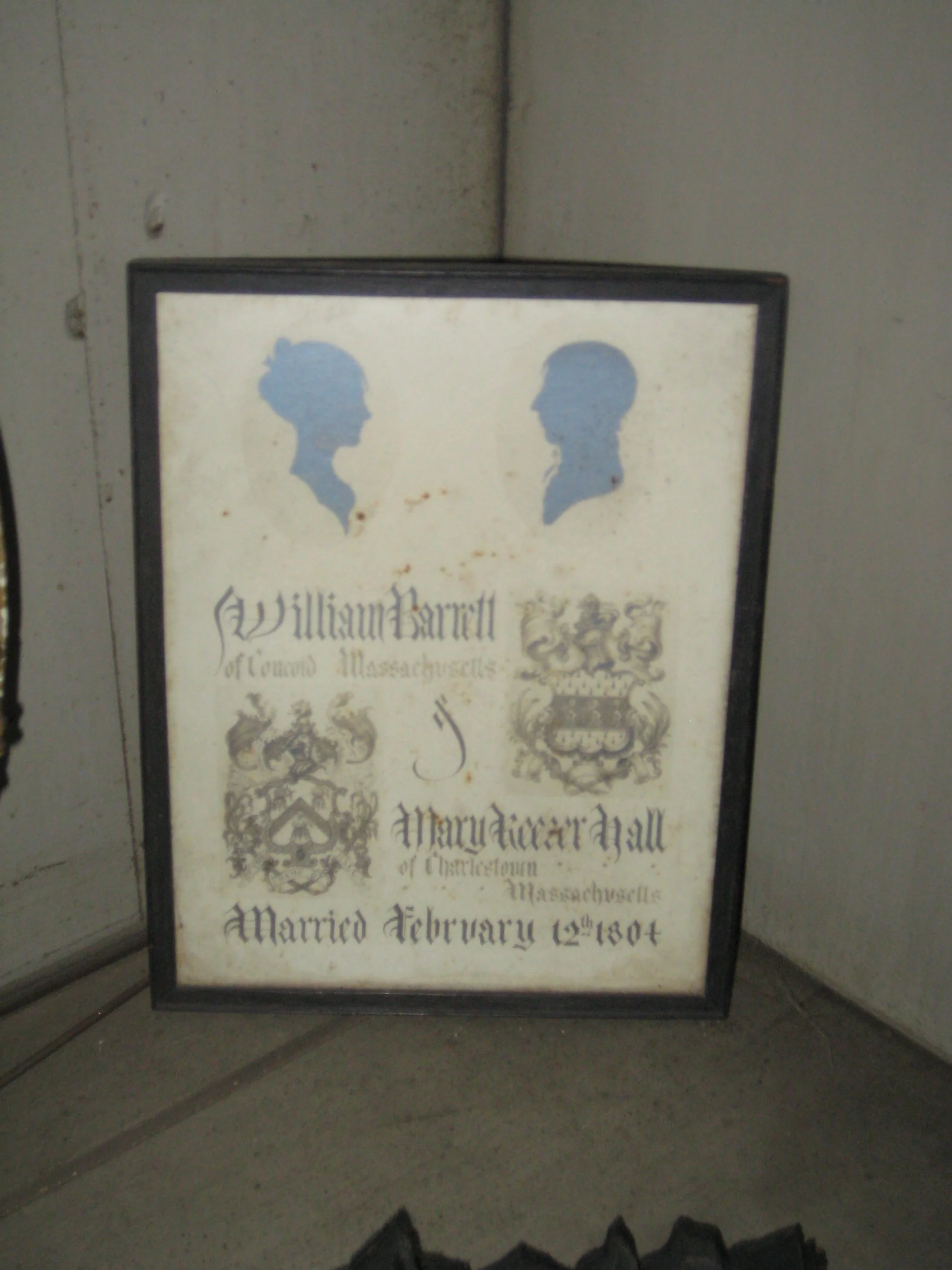

Marriage document describing William Barrett of Concord, MA and his marriage to Mary Keiser Hall of Charlestown, MA

Within the closet sits the profiles of William Barrett (1775-1834) and Mary Keezer (Keiser) Hall (1785-1870). This framed piece serves to commemorate the marriage between the two, as well as the joining of the two families as a result. Underneath the silhouettes are each of the respective coats of arms for both the Barrett family (on the right), and Hall family (on the left). The two were married on February 12th, 1804 as detailed within the piece; at this moment in history, the displaying of a family’s coat of arms would have been typical of high-class identification. This practice of heraldry—to display a coat of arms within society—was a way that those within the upper class referenced the rituals of a distant past, holding honor and sophistication within its elaborate patterns. A coat of arms was a hereditary device to display status, originally developed in Europe in the mid-12th century and used by the upper echelon of society: nobility, royalty, and others who were the primary power holders within Western Europe. The reference to this past was one that was carried into America to establish this higher class, more sophisticated to even be looking back on the European nobles within history, and displaying a prestigious family name to this same effect. It is clear from this fact alone that both families were wealthy and of high standing, both displaying a coat of arms in the official joining of the two families through marriage.

The two silhouettes in this piece are seen at the top, showcasing the wedded couple above their names and respective coat of arms. Created using black ink on white paper, these silhouettes are not as detailed as some of the other silhouettes in the Museum’s collection. This choice to make the simplistic view of the couple that we see, allows the viewer to not get lost in all of the detail within the piece - as the busy scene describing their marriage below would clash with a “bronzing” technique or later added detailing, as seen in other pieces around the house. Placing the figures at the top of the piece communicates their importance while also keeping the viewer engaged with all portions of the commemorative wedding piece. So much detailing is added to the gothic font that is chosen for the names, their places of origin, as well as the date; coupled with both of the beautiful and circumstantial coat of arms—any more detail would have been lost. The placement of all of the words and imagery was intentional and guides the viewer through the piece, conveying importance, class status, and remembrance in a medium-sized frame.

Familial and Societal Context

Genealogy Tree with Lily St. Agnam Barrett’s connection highlighted (red circle)

When figuring out ties to the central family tree that is used in the museum and on tours, a large portion of the pieces kept in the SE Bedchamber trace back to the wife of George Putnam Huntington (1844-1904)— Lily St. Agnam Barrett (1848-1926) and her own genealogy. After searching through our records and various family trees, William Barrett and his wife Mary Keiser Hall would have been the grandparents of Lily. Knowing this, as well as that Lily would have brought the paper indication of her grandparent’s marriage to Forty Acres shows how her familial ties were incorporated into the home for her own remembrance and display of her ancestry, independent of that of the Porter-Phelps-Huntington lineage. This added union of the Barrett family provides more societal context into the family’s relations within society as the Barrett family were major in their own respective trades in society, William Barrett especially was significant in the cloth dyeing business, securing patents on the many processes that he had developed with his employees.

News article describing Barrett’s company line

William Barrett started his original textile dyeing business under the name of “William Barrett & Co.” in Malden, MA in 1801. However, this business shifted over time and changed courses with the longevity of William’s involvement in the trade, and in 1804 he rebranded (the same year he got married!). It was in this year that William started a new company and was motivated beyond the Boston market - his attention being turned to New York as a means of reaching higher markets and easier access to mid-Atlantic and Southern coastal cities. Because of this, William bought an old mill and opened his new factory in 1819 under the rebranded business name of “Barrett Tileston & Company” which encompassed a new partnership between himself and William Tileston, his brother, and his nephew. The company would then shift management and titles for the rest of its longstanding history, outliving William Barrett by 105 years, the factory left abandoned in 1939, which later collapsed that same year.

Newspaper article from 1939 describing the Barrett Factory’s collapse

Within the ‘Barrett Room’ or SE Bedchamber as well sit another set of silhouettes commemorating the same couple. An oval shaped frame encompasses a more detailed set of silhouettes done for William Barrett and his wife Mary Keiser Hall. Through our records within our collection it is noted that the couple was married in 1804, so due to reasonable suspicion it can be assumed that these portraits done of William and Mary date to the same year as their marriage document. However, since the last piece was a complete look at the two and their backgrounds, this piece serves to capture more of the detail of the couple as individuals in this important moment in their lives.

Technique and Procedure

Wedding silhouette done of William Barrett and his wife, Mary Keiser Hall

The two silhouettes in this one frame fall under the “hollow-cut” form that is used throughout the house, but prove different as the white paper that has been cut to reveal the profiles of the couple has been laid over a dark fabric, instead of another sheet of paper. The use of fabric to achieve the same effect as paper in other silhouettes around the home serve the same purpose—revealing the silhouette cut from white paper. The detailing done to the clothing befitting both of the figures has not been done with later-added ink, instead just a detailed cutting job that showcases the elaborate hair on Mary and the fancy dress on William—possibly their wedding outfits. The gold framing adds significance to this piece and makes the lasting effect feel more important and emphasized, especially with such a simplistic set of silhouettes being displayed within the gold borders. The paper has significantly aged over time, appearing fully yellowed, signaling the amount of time that has passed since the creation of the two profiles in 1804.

Conclusion and Significance

All of the pieces discussed are an exciting part of the collection on-site that serve as one of the earliest forms of self-reflection. Whether the silhouettes be done through the very common “hollow-cut” technique alive at the farmstead, later added detailing with various kinds of inking (bronze, gold, black), or through elaborate framing— each of these facets serve the individual silhouettes by communicating importance even to the eyes of viewers today. Whether this be done by intentionally shading only the clothing on one’s bust to communicate dimension and prestige, or framing which draws the viewer’s eye to the center; each presents a feeling of importance to the figure captured within the silhouette. The collection of silhouettes that reside at Forty Acres is a testament to the progression of technology alive within the era of their creation. One example of this technology is the “hollow-cut” technique which involves the cutting of a white paper silhouette and laying it over black paper exhibits tact and skill, with later added details being used to add humanity back to the piece. All unique in their own way, each silhouette technique lends its own hints into the lives of the people receiving the service, as well as the artist themselves. Every choice had to be deliberate, especially within the bounds of such a simple yet complex art form.

Early modes of photography offered before photographs aid in the commemorative nature that these pieces hailed, similar to how we keep photographs of our loved ones sprinkled throughout and around our homes. They aid us in our research on individuals and kinship ties; just by having a silhouette in the home proves the family networks that were alive within Forty Acres. Whether this be the several wives who married into the family who brought their own silhouettes of extended family members with them, the early silhouettes of children who stand to represent the fourth generation of siblings in the family, or a young ambitious merchant and his first wife in the fashionable city of Boston. Having these in our collection better helps our understanding of relations across generations, way before times when one could express this through photography within homes. It is fascinating to see the pieces of familial expression tied to all of the silhouettes within the home— the ways in which they all serve the intended purpose in preserving one’s livelihood through documentation.

Sources:

Conn, Carole. “American Silhouettes of the 18th and 19th Centuries.” CT Country Antiques, 3 June 2021, www.ctcountryantiques.com/post/american-silhouettes-of-the-18th-and-19th-centuries.

Welter, Lisa. “Types, Techniques and Analysis of Silhouettes.” Arlington Historical Society, 10 Feb. 2021, arlingtonhistorical.org/types-techniques-and-analysis-of-silhouettes/#:~:text=With%20hollow%2Dcut%20silhouettes%2C%20the,outlined%20profile%20of%20the%20subject.

Smithsonian American Art Museum. “William M. S. Doyle.” Smithsonian American Art Museum, americanart.si.edu/artist/william-m-s-doyle-1337.

Silhouette Production Techniques | profilesofthepast.org.uk. www.profilesofthepast.org.uk/content/silhouette-production-techniques-0#:~:text=In%20the%2019th%20century%20'bronzing,of%20various%20shades%20and%20depths

The Social and Cultural Significance of Victorian Heraldry. victorianweb.org/history/heraldry/introduction.html.

“The History of Coats of Arms and Heraldry | Historic UK.” Historic UK, 29 Nov. 2023, www.historic-uk.com/CultureUK/Coats-of-Arms.

Veronica. “Workday Wednesday: Barrett Nephews and Company.” GenealogySisters, 31 Jan. 2018, genealogysisters.com/2018/01/31/workday-wednesday-barrett-nephews-company.