Adapted from “A Wind that Rose”: Susan Davis Phelps and the Poet

by Anna Plummer

Susan Davis Phelps (1827-1865) [1a].

The Phelps and Huntington families knew the now famous Dickinsons of Amherst well. But one friendship with the poet herself stands apart…

“Vivacious and curley haired”[1] Susan Davis Phelps was the youngest of nine children who lived at Phelps Farm, the daughter of (Moses) Charles Porter Phelps and his second wife Charlotte. Susan grew up just across the road from her Huntington relatives at Forty Acres and was well-acquainted with society in Amherst, where she may have attended school as a child and where she formed close friendships in her adulthood. She is known for the most romantic, quintessentially Victorian New England details of her life – that she died in her thirties of “a broken heart” after her former fiancé married another woman and because she was a friend of Emily Dickinson. The date of her funeral is inscribed on two of Dickinson’s poems, revealing a more impactful relationship than has traditionally been acknowledged. The smattering of family diary entries so far studied reference a sick and fretful young woman, but a closer look at the rich documentation of her family and community, as well as some of her own special vestiges, reveal Susan Phelps with vibrancy - as a singer, baker, painter, socializer, an aunt, a loving sibling, and a lasting friend.

FAMILY

By Susan’s birth, the Phelps family was eleven-children strong, and their beautiful New England farm bustled with chores and company. Susan was only three years old when her biological mother died, so she relied on a complex weave of older half-sisters and her step mother for female nurturing and support. She and her direct siblings formed an especially tight bond that molded her sense of self. Along with Susan, the children of Charles’ second wife were Theophilus, William, and Charlotte (named after her mother). Susan also developed a particular fondness for her half-brother Arthur and her much older siblings Sarah and Charles who, like Susan, remained at Phelps farm for their entire lives. It was among this unique collection of Phelpses that Susan grew to maturity. As one of the few who stayed, she remained rooted in the place where those people had shaped her through their scolding, doting, teasing, their achievements and mistakes, and their love. Click on the portraits[2] below to learn about Susan’s closest siblings.

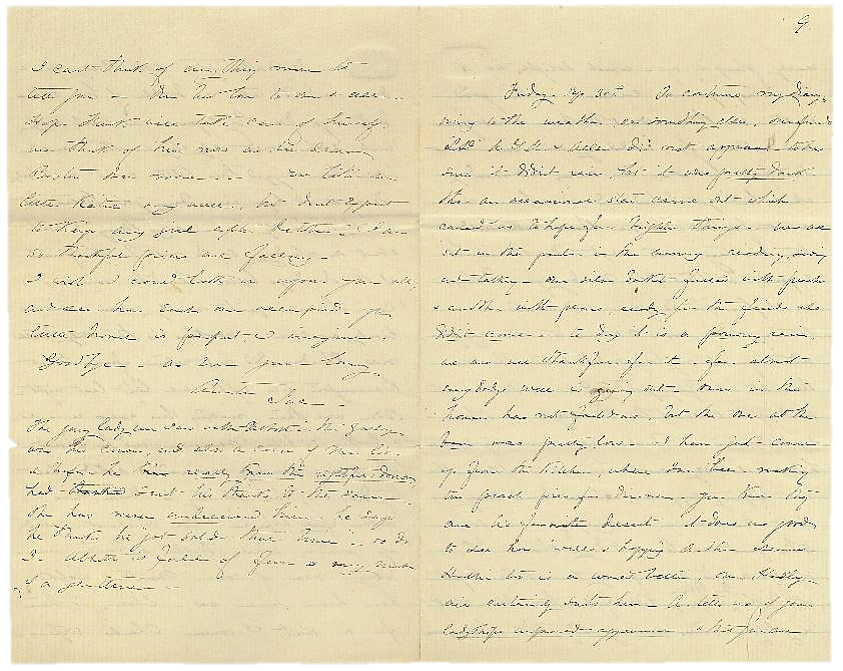

SUSAN IN SOCIETY: A LETTER

Susan’s letter to Ellen Bullfinch, 1864.

Just one document in the Porter-Phelps-Huntington Collection preserves the exuberant dashes and lively social recountings frequently written by Susan Phelps. On a Thursday in 1864, she had a busy week both behind and ahead of her as she launched into these ten pages addressed to her twenty-something niece, Ellen Bullfinch. “I am constrained to take time by the forelock,” she wrote, “so will commence the weekly today” (Phelps, Susan). The tidings that follow offer a window into the woman’s life in full blossom four years after her broken engagement - and just one year before her death. Her words express an enthusiasm for social involvement in the Amherst College community in the midst of Civil War years - and allude to her family friendship with the Dickinsons.

The letter recounts her attendance at what was probably “an exhibition of physical culture”[3] and military drills at Amherst College, or as she calls it, “that city on a hill.” In her words,

... few were in the gallery then so we took possession of the best seats… The sophomores were almost through their half [horn?], but they seemed to be under very good discipline, they marched well, & we heard them sing “When Johnny Comes Marching Home”. The only face we knew among them was that young man from Hatfield the Dickinsons are educating - have forgotten his name - The hall was not empty long - perhaps fifteen minutes in which we laughed and chatted, waiting as patiently as we could.

(Phelps, Susan)

From Professor Edward Hitchcock to the handsome senior Susan noted was “still pale” after his return from the battlefields of the Civil War, the letter reveals that Susan maintained a wealth of friendships at Amherst College. This was years after her courtship and long engagement with an Amherst College graduate ended as a result of several possible family and health-related factors. Contrary to the “broken heart” myth, the letter does not reveal loneliness, or a sense of being out of place in her environment. Yet Susan did not confide her deepest thoughts in her younger niece, at least here. Maybe such thoughts were reserved for her sister Charlotte and her closest peers, like Emily Dickinson.

The Dickinsons, of course, were other friends that kept Susan and her family tied to Amherst through the Civil War years. Since Susan and Emily’s friendship began through Susan’s engagement to Henry Emmons in 1854, seems only to have strengthened after the engagement broke off in 1860, and then continued through the end of Susan’s life (1865), their closest years exactly spanned the Civil War. Their friendship also spanned, therefore, Emily Dickinson’s most productive writing years. While Susan applauded at the exhibition, and even sang at the piano upon her friends’ insistence, Emily would have avoided such a public event and its military pomp and circumstance. But each woman responded in her own way to national - and personal - turbulence. Dickinson sometimes applauded the military hero in her poetry. She wrote:

It may be – a Renown to live –

I think the Men who die –

Those unsustained – Saviors –

Present Divinity –

(Fr524)

In the same year as Susan’s letter, however, Dickinson would write to a Norcross cousin, “sorrow seems more general than it did, and not the estate of a few persons, since the war began; and if the anguish of others helped one with ones own, now would be many medicines” (L298).

Curiously, Dickinson seemed successful in offering that sympathetic medicine in the letter that best marks her friendship with Susan Phelps. A paraphrase of Isaiah 43:2, with an enclosed rosebud, said “When thou goest through the Waters, I will go with thee” just days after Susan ended her engagement (L221). The recipient slipped the rosebud into her personal Bible, where it remained for over a century (Leyda). Its last public viewer, Jay Leyda, did not note between which pages.

DICKINSON’S REMEMBRANCE

The poet experienced a flurry of change and activity in her life from 1860 to 1865, yet during this time, Dickinson’s friendship with Susan Phelps deepened. Emily and Susan had met in 1854, after which the former told Emmons with excitement, “Of her I cannot write, yet I do thank the Father who’s given her to you, and wait impatiently to speak with you… My hand trembles…” (L169) and reported to Susan Dickinson “Her name is Susie too, and that endeared me to her” (L172). But even after Susan Phelps ended her engagement with Emmons in 1860, visits and correspondence with Emily Dickinson persisted. The most fertile evidence of their friendship, however, may lie in its aftermath.

The friendship’s abrupt conclusion left Dickinson emotionally raw. On December 5th, 1865, the day of the funeral, The Springfield Republican – which the Dickinsons subscribed to – reported Susan’s death. Public records attributed no cause to Susan’s death, although family writing attests that she had succumbed to some severe illness. Within days of the news, Emily reached out to like friends for stability and assurance. In a letter to Susan Dickinson, she called woundedly on the reasoning of providence, then in the concluding verse funneled her thoughts into a balance of sorrow – and gratitude for the friends that remained. Her succeeding note to Elizabeth Holland voiced continued grief as she wrote, “It was incredibly sweet that Austin had seen you… to see one who had seen you was a strange assurance. It helped me dispel the fear that you departed too…” (L313).

And years later, Dickinson would still recall the day. On two poems – “A Wind that rose though not a Leaf” (Fr1216C) and “The Days that we can spare” (Fr1229C) the poet inscribed the date of Susan Phelps’ funeral on her personal copies[4]. Both take on themes of loss and memory. Yet as she sat alone to compose “A Wind that rose”, probably six years after Susan’s death, the pain of a memory seems to have accompanied joyful gratitude for the friend’s life. Here is the elegaic verse punctuated with “December 5th”:

A Wind that rose though not a Leaf

In any Forest stirred —

But with itself did cold commune

Beyond the realm of Bird.

A Wind that woke a lone Delight

Like Separation's Swell —

Restored in Arctic confidence

To the invisible.

(Miller 504)

Something rose through Dickinson - maybe on the date’s anniversary, or nudged by an imperceptible reminder - and she recalled the sweet imagination of Susan Phelps. A wind that doesn’t blow on the earth is the spirit of a departed soul; this wind lives “Beyond the realm of Bird” – a phrase that flirts with heaven. It has left its initial world and companions, allowing for the mutual “swell” of separation. Then, its “stir” brings a joyful moment of reconnection.

The manuscript of “A Wind that rose” found in Dickinson’s personal collection, with inscription.

The poem wonders at the nature of remembering: how do the living engage with those they have lost? We try, with occasional success, to meet them in our thoughts, and we can also sense and recall them without warning or effort. Either way, the stirring is felt and, oftentimes, peacefully received. If the wind is a mobile spirit (that comes from the cold to stir up memory), the words suggest that the departed occasionally breathe on us, for their own comfort. For Dickinson, it must have been a deeper comfort indeed, to imagine that her remembrance was also the remembered’s delight.

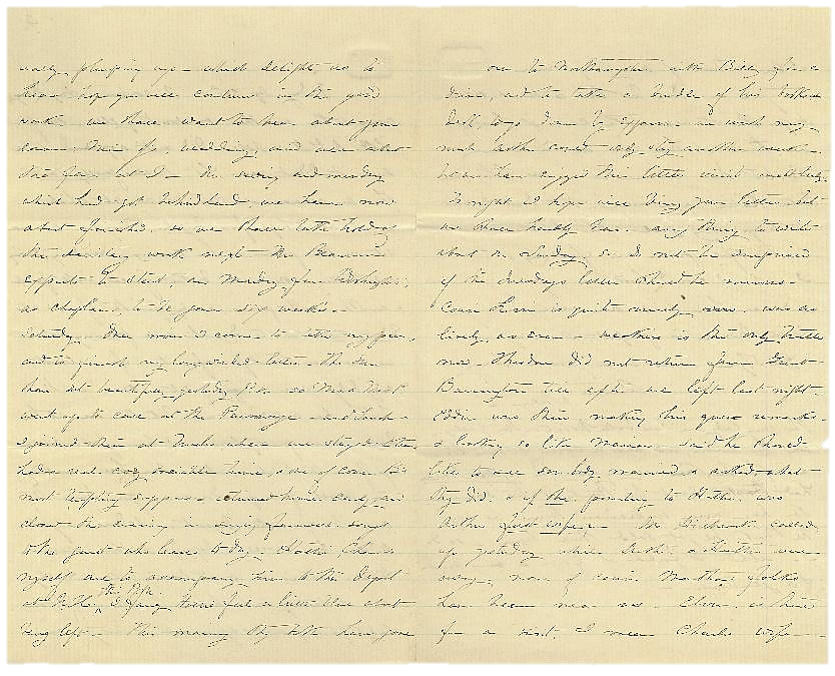

The conclusion of Charlotte Phelps’ letter to Ellen Bullfinch, c.1870

A SISTER’S GRIEF

December 5th and 2nd became etched into the memory of several besides Dickinson. Charlotte, Eliza, Billy, Charles, Arthur, Sarah, and Marianne turned around from the death of their stepmother, Elizabeth Judkins Phelps’, in November to watch as, in a few days, their youngest sister tried to stifle her distress, grew anxious, short of breath, and after a long, rainy night - left them forever. The oldest Phelps brother, Charles, recorded in his “Journal of Farm Works” that a second doctor’s consultation on Friday, December 1st, still “gave no hope” for Susan, and on Saturday, the Express reported her passing (Leyda). There is no certificate of death. In an undated letter most likely sent four to five years later, Charlotte alluded to the same meaningful dates as she wrote to their niece Ellen Bullfinch, the young woman to whom Susan had recounted pie-making and college excitement. The letter begins, “Dear Nellie, The watch stand is a very pretty remembrance of my dear home, & my dear niece” (Phelps, Charlotte). Though generous and generally positive, Charlotte’s efforts pale in comparison to her sister’s letter. Charlotte’s stunted note reveals a homesickness for the complete Phelps family which she could never regain. She speaks kindly on the “business” of mending and tailoring, but her mind returns to remembrance. Here she may reference an anniversary of Susan’s funeral.

I suppose Auntie has told you where we have already been. I knew you would remember the 2nd of Dec. & also the 5th as I too shall never forget other days alike long to be remembered for a similar reason. God bless & keep you ever more –

Your aff. Aunt C.

Unlike Susan, Charlotte married in 1869 and moved away; the delicate “B” embossed on her stationary stands for Bartlett, the name of a Tennessee university president to whom Charlotte became the fourth wife (“Massachusetts, Marriage Records”). But Charlotte’s prolonged reaction to her sister’s death indicated her own broken heart. Theodore G. Huntington, older brother to Frederic Dan Huntington and cousin to the Phelps children, described her grief in his “Sketches of Family Life in Hadley”. While Susan’s death “made a great gap in the family[,] she was so sweet tempered and sympathetic”... to Charlotte the loss was “irreplaceable.”

... and this not alone because she was a loving sister, companion, and confidant, but I think it must have been Susan who kept the poise of her life. Her death was like taking the balance wheel from the water. It almost seemed as if she was the centripetal power that bound them both to a common orbit and that loosing her, she was henceforth in her solitary course to be the sport of any malign influence that might cross her path.

(Huntington 55)

Of her own sister, Dickinson would write, “When she is well, time leaps. When she is ill, he lags, or stops entirely. Sisters are brittle things” (L207). With Susan gone entirely, Charlotte became restless at home. She planned frequent absences, sending Theophilus to board with a neighbor and Billy to the Huntingtons, then went to live in Boston for months at a time. Charlotte married quickly and moved to Tennessee, but allegedly abhorred her married life there until “her health at length gave way.” The next visit home to Hadley revealed “unmistakable signs of insanity,” reported Huntington, then tragically, while at an asylum in Hartford, Charlotte took her own life. In a family already prone to anxiety and mental illness, Susan’s passing had thrown an unmitigable shadow.

MEMORIAL

The northeast (formerly southwest) sanctuary window memorializing Susan Phelps. Made by William Gibson and installed in 1866 (Samonds).

The departure of the youngest Phelps daughter left a painful emptiness in her family and community, but her legacy is hopeful and resonant, as experienced in the bright colors of a stained glass memorial, as well as the stirring words of Dickinson’s poetry. The summer after Susan’s death, the Express announced the consecration of the first Episcopal church building in Amherst. The paper reported that at Grace Church (still standing near Amherst’s town center), “[t]he first window on the south side is in memory of Miss Susan D. Phelps of Hadley” (Leyda). The featured verses and symbols on her window reach pleadingly for a resolution to Susan’s tragedy. Her ultimately fatal period of illness bears only speculative links to the trauma of her stepmother’s death one month prior and of learning that Emmons, her former fiancé, had married, but every factor seemed to exacerbate her early decline. Centered on red vesica pisces shapes, “My soul waiteth for the Lord / Until the day break and the shadows flee away” combines two verses from the Bible (Samonds). Susan’s patience, and perhaps her faith, endured a great deal of shadow. Atop, on ocean blue and an anchor symbolizing God’s grace, reads “I look for the resurrection of the dead” a line of hope for those engaged in her remembrance below.

Dickinson knew about the window. But it was past her hour for church attendance, and, problematically, it was not her church (Eberwein 17-18). Could she have missed it? Likely not. It might have taken her six-odd years [5]. And then, quietly, sneaking into the empty sanctuary on a winter’s day, she looked up— and perhaps a wind stirred …

Bridging the Past and Present:

A Wind That Rose: Susan Phelps and Emily Dickinson

August 5, 2021

Below is the recording of Anna Plummer’s presentation of her findings from her historic and creative research paper which delves into the above subject – the life of Emily Dickinson’s friend and member of the Porter-Phelps-Huntington family, Susan Davis Phelps (1827-1865). This was the penultimate installment of PPH’s 2021 speaker series Bridging the Past and Present made possible by a grant from the Bridge Street Fund, a special initiative from Mass Humanities to enable open access to local histories.

Notes

[1a] Portrait published in The Years and Hours of Emily Dickinson, by Jay Leyda.

[1] Ruth (Huntington) Sessions’ descriptions of her older cousins has a penchant for the dramatic. See Sessions 128.

[2] All portraits and manuscript scans courtesy of Archives and Special Collections, Amherst College Library, unless otherwise noted.

[3] See Schedule of Exercises at the Sawyer Prize Exhibition of Physical Culture.

[4] Dickinson also sent versions of the two poems to Susan Dickinson and Thomas Wentworth Higginson (Miller 504).

[5] The time between Susan’s death and the year Dickinson likely wrote “A Wind that rose” and “The Days that we can spare” (Miller 504, 509).

Works Cited

Dickinson, Emily, “A wind that rose though not a leaf,” Amherst Manuscript #118 in Box 2, Folder 40, Emily Dickinson Collections, Archives and Special Collections, Amherst College Library.

____________, and Cristanne Miller. Emily Dickinson’s Poems: As She Preserved Them. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2016.

____________, and Ralph William Franklin. The Poems of Emily Dickinson. Reading ed., 3. pr. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard Univ. Press, 2003.

____________ .“The days that we can spare,” Amherst Manuscript #390 in Box 5, Folder 30, Emily Dickinson Collections, Archives and Special Collections, Amherst College Library.

____________, and Thomas Herbert Johnson. Selected Letters. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press, 1986.

Eberwein, Jane Donahue. “Where Congregations Ne’er Break Up”: Dickinson’s and Amherst’s First Church. Unpublished.

Habegger, Alfred. My Wars Are Laid Away in Books: The Life of Emily Dickinson. New York: Modern Library, 2002.

Huntington, Theodore G. Sketches of Life in Hadley; Letters to Helen Frances Huntington (Quincy) describing life in Hadley. (Published in Boston in 1883 for private circulation.) in the Porter-Phelps-Huntington Family Papers, Amherst College Archives and Special Collections, Amherst College Library.

Leyda, Jay. Susan Phelps - notes about her relationship to the Dickinson family, from the Porter-Phelps-Huntington Family Papers, Amherst College Archives and Special Collections, Amherst College Library.

________. The Years and Hours of Emily Dickinson. Hamden, Conn.: Archon Books, 1970.

“Massachusetts, Marriage Records, 1840-1915 for Charlotte Elizabeth Phelps” AncestryLibrary.Com. Accessed November 18, 2019.

“Massachusetts, State Census, 1855.” AncestryLibrary.Com. Accessed November 20, 2019.

Phelps, Charlotte. Received by Ellen Bullfinch, 1867?, from the Porter-Phelps-Huntington Family Papers, Amherst College Archives and Special Collections, Amherst College Library.

Phelps, Susan Davis. Received by Ellen Bullfinch, 29 Sept. 1864, in the Porter-Phelps-Huntington Family Papers, Amherst College Archives and Special Collections, Amherst College Library.

Photographs of the Phelps family, from the Porter-Phelps-Huntington Family Papers, Amherst College Archives and Special Collections, Amherst College Library.

Samonds, Ken. “North 2 - In Memory of Susan Davis Phelps.” Grace Episcopal Church, Amherst, MA.

Schedule of Exercises at the Sawyer Prize Exhibition of Physical Culture, in Amherst College : At the Barrett Gymnasium, on Saturday Afternoon, Nov. 23d, 1867, at 2 o’clock. J.L. Skinner, printer, 1867. Amherst College Archives and Special Collections, Amherst College Library. Accessed October 15, 2019.

Sessions, Ruth Huntington. Sixty Odd: A Personal History. Brattleboro: Steven Daye Press, 1936.

![Susan Davis Phelps (1827-1865) [1a].](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/53cd26f2e4b03157ad2850da/1593547528060-PIALI6QOGU517G9KAW5L/Susan%2BPhelps%2B2.jpg)