Postcards From an Imagined Early America

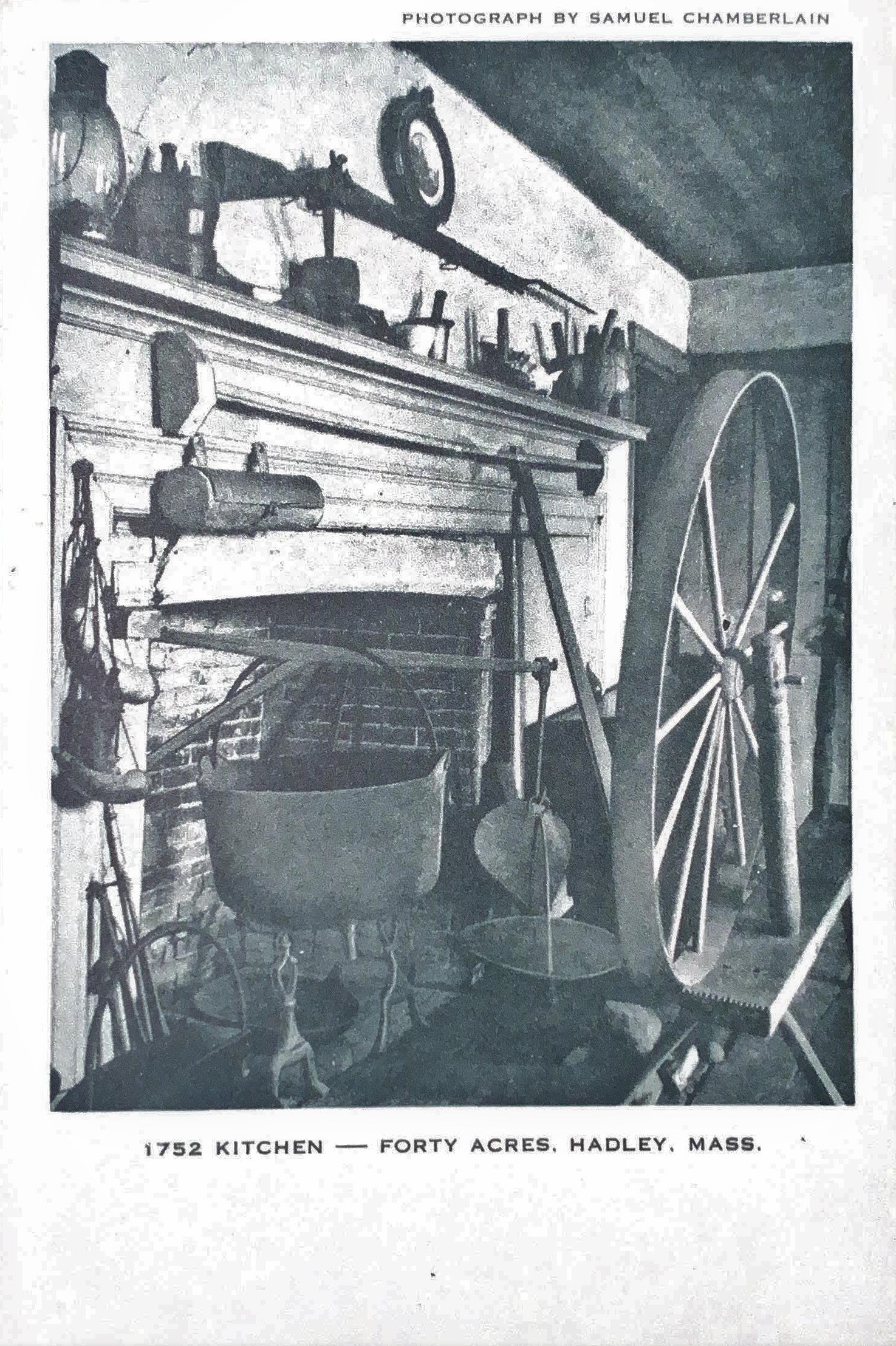

1752 Kitchen- Forty Acres. Hadley Mass,

Photograph by Samuel Chamberlain

It is easy to dismiss images like the one on this mid twentieth-century postcard as out of date and romantic--and therefore irrelevant imaginings of the past. But nothing could be further from the truth, as I argue in my recent book Entangled Lives: Labor, Livelihood, and Landscapes of Change in Rural Massachusetts. [1] Instead, images like this one help us to understand the lens through which we see the early American past; grappling with them is, then, essential to our ability to imagine and comprehend both the past and the present.

Entangled Lives is a book more than twenty years in the making—and one thoroughly grounded in the collections, archives and spaces of the Porter-Phelps-Huntington Foundation. An outgrowth of my 1997 PhD dissertation, the research seeks to excavate the deeply braided lives of white, black, and Indigenous women in post-revolutionary Hadley in order to explore and recover social relations of labor among women in early New England. It sits alongside my other writings about women in the Connecticut Valley – The Needle’s Eye: Women and Work in the Age of Revolution (UMass Press, 2006) and Rebecca Dickinson: Independence for a New England Woman (Routledge, 2013) – and seeks to enlarge our appreciation for the ways in which these rural women’s lives were mutually interdependent. In chapters that explore women’s work in domestic service, clothmaking, hospitality work and caregiving, it builds out larger arguments made in my earlier work on the clothing trades, to show how labor relations drew women together and set them apart in a post-Revolutionary society that was rapidly evolving.

Less formally, it is essentially a love letter to the everyday, unheralded labors of women whose lives rarely loom large in popular historical imagination. Native basketmakers and White nurses; Black laundresses; tavern keepers and workers; spinners, weavers, and fullers; servants of all kinds—the work seeks to revisit the social relations of labor in early Hadley from as many points of view as possible.

The book concludes with a contemplation of how we today have come to understand that history, and considers the role of past generations of cultural production in creating popular historical imagination today. Along with my generation of public historians, I have become increasingly interested in reflective practice. [2] It is important not only to study the past, but also to pay attention to the history of interpretation itself, and the ways in which the apprehensions and misapprehensions of previous generations shape both the work we do now, and the ways audiences receive it.

And that’s where this image, and postcard, comes in.

The work of museum founder James Lincoln Huntington is explored elsewhere on this website. It was Huntington whose interpretive interests and priorities created this postcard. The image is credited to “Samuel Chamberlain,” and was taken in 1948. By that year, author, photographer and graphic artist Samuel Vance Chamberlain (1895-1975) was a well-known figure among curators and preservationists. [3] He had studied architecture but gravitated instead to a career as an artist. In the 1920s and 30s, he established his reputation as the creator of drypoints, etchings, and lithographs of scenes across Europe and the U.S. In the last half of the 1930s, he segued into photography, publishing a series of books documenting “American Landscapes”—historic New England communities like Salem, Gloucester, and Marblehead—and then a highly successful series of illustrated calendars.

By the time Huntington invited Chamberlain to photograph Forty Acres, the latter “was now not only a well-respected photographer of the American Scene, but also the author of handsome books that did much to stimulate both the tourism industry and the historic preservation movement in New England.” [4]

James Lincoln Huntington had shifted his residence from Boston to Hadley in 1943, and by 1948, Huntington’s vision for the house had begun to take shape. As I discuss in Entangled Lives, the farm’s labor history lay beyond his interest, focused as it was with celebrating his family’s genteel history, and particularly in the context of the heritage and ancestry of his grandfather Frederic Dan Huntington, the first Protestant Episcopal bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Central New York (the title of Huntington’s book being Forty Acres: The Story of the Bishop Huntington House).

Huntington was not especially interested in the farm’s labor history, willing to let go of structures and artifacts that reflected that theme. But as it happens, across town, another pastkeeping enterprise was interested in precisely that. In 1930, the Johnson family—particularly bookseller Henry Johnson and his brother, author and photographer Clifton Johnson-- launched the Hadley Farm Museum. As collectors, the Johnsons specifically eschewed preserving “furniture, costumes, and the indoor household life,” items that they believed were already well attended to in the region’s cultural institutions. They preferred to begin their work “at the back door.” [5] They had been looking for a venue to house their enterprise, approaching James Lincoln Huntington about building a replica of the barn at Forty Acres. Huntington offered to sell the structure itself, and in 1930 the Hadley Farm Museum opened in the Phelps barn, removed from its original location and moved to its new site in the town center.

But certain artifacts related to early American work did appeal to Huntington, and would be documented in the important image captured on this postcard, created by Chamberlain. In the years just prior to the publication of Huntington’s Forty Acres, Chamberlain had brought out two works that surely caught Huntington’s eye, and captured his fancy. In 1946, M.A. DeWolf Howe’s Boston Landmarks, with photographs by Chamberlain, appeared, and in 1947, Chamberlain published Behold Williamsburg: A Pictorial Tour of Virginia's Colonial Capital. [6] A similar project with this prominent photographer would help put Forty Acres on the map among the nation’s most important historic sites.

How and when the two men met is not yet known. It is possible that they encountered one another through their shared interest in the Colonial Society of Massachusetts (founded in 1892, one of the many heritage societies that defined the lives of influential New Englanders in these years). Huntington had been elected to membership in April 1929; Chamberlain was elected to membership in December 1947 (membership at this time was only open to descendants of the colonists of Massachusetts Bay or Plymouth; today the CSM is a “non-profit educational foundation designed to promote the study of Massachusetts history from earliest settlement through the first decades of the nineteenth century”).

By the Saturday afternoon in mid May 1948 that twenty-six members of the Colonial Society journeyed to Hadley, the barn’s foundations had been converted to a fashionable sunken garden. [7] The group visited Hadley’s 1808 meetinghouse (where they surely were shown the communion silver gifted by Elizabeth Porter Phelps), and toured the Hadley Farm Museum before heading on to Forty Acres. [8] Members were gifted a copy of Huntington’s book, and Chamberlain’s images.

The photograph captures both Huntington’s vision, and Chamberlain’s. When the Johnsons came to take the barn, Huntington suggested that they may also help themselves to whatever implements seemed of interest for their new enterprise; an apple parer bearing the initials of Elizabeth Whiting Phelps (and so, dating from prior to her 1801 marriage), on view today at the Hadley Farm Museum, was likely among the objects acquired. And so the tools visible in this 1948 image take on additional significance, being among those Huntington specifically prioritized for interpretation, and Chamberlain selected as in keeping with his own influential perspective on the past.

Huntington’s caption in his book says that “This is the original kitchen fireplace built in 1752 and used until 1771. The musket with bayonet attached was used in the local company at the time of the War of 1812.” [9] Huntington was mistaken in his understanding of the house’s architectural evolution: the image in fact shows the hearth of a kitchen addition built a half-century later, added to accommodate the growing household as the children of Charles and Elizabeth Phelps reached adulthood. But the constellation of artifacts captured here tells us a good deal about Huntington’s interpretive agenda. The installation and image contain several iconic elements of early American material culture. The gun over the mantle, accompanied as it is here by two powder horns, was a mainstay of mid-century house museum interpretation, as are the pair of lanterns and cylindrical candle box so prominent in the foreground.

But any image of a hearth, and this one in the “1752 kitchen,” is necessarily principally a reference to the women of Forty Acres. Across the mantle sit a number of mortars and pestles, marking work related to both food preparation and healthcare. The trammel and cookware visible, too, mark important aspects of women’s work. Most notably, it is also no surprise that the large spinning wheel—a wool wheel likely once operated by Elizabeth Whiting Phelps—made the cut. From the late nineteenth century onward, the spinning wheel had become an iconic symbol of early American women’s work. Viewers would have immediately registered the object as a symbol of women’s steady labor in cloth production.

The “women” of the viewer’s historical imagination would have been the “Modern Priscilla” by then well developed across popular culture, from magazines to sheet music, in public pageantry and popular cultural. [10] Nowhere to be seen in the era’s envisioning of the past were the indigenous women whose labors as domestic servants kept the household running smoothly, or native craftswomen whose skills in basketry kept the farm furnished with containers, tools for food preparation and storage, and chair seats; or the enslaved and later free African American women who kept the family’s clothing in good order, and advanced the aims of Elizabeth Phelps’ profitable dairy.

Parade float, Hadley quarter millennial celebration, 1909. The large wool wheel that serves as the centerpiece of this tableau of the “old time kitchen” reflects the importance of wheels in the imagining of women’s work in Hadley’s past.

The appeal of spinning wheels as symbols of women’s lives had long-term appeal—and endures today. Some fifteen years or so after Chamberlain created the image for Huntington’s book, its broader dissemination was made possible by the creation of this postcard. The Artvue Post Card Co postcard, which lists the museum’s five-digit zip code, postdates 1963, when such codes were introduced.

In more recent years, the museum has worked hard to overcome these romantic visions of the early American past, and today offers a sophisticated retelling of the many ways that very different kinds of women labored around Forty Acres, in complex relationships that involved affection and coercion, intimacy and resistance, grounded in asymmetrical interdependence. As I explain in Entangled Lives’ “Coda,” the museum embraced the thriving scholarship on women and work that first emerged in the 1980s and 90s, launching a reinterpretation initiative that foregrounded the experiences of enslaved and laboring women at Forty Acres. [11] Since that time, a number of efforts have continued to bring scholars of early American women’s history to the site, continuing to deepen understanding of these rich collections.

Exploring the years of pastkeeping that preceded that development, and engaging in reflective practice, strengthens and deepens our understanding of how we engage early American women’s labor history. Postcards like these help connect the past and the present, reminding us of the generations in between whose efforts preserved the raw materials of the past, but in ways that were selective and partial. Our challenge is to appreciate their work in both its achievements and shortcomings, and to use our own skills to identify the silences their choices created, and to develop new methodologies and approaches to address them. Put another way, we receive these postcards, attend to the sender and to the postmark, and then try to see beyond the frame.

Support our local book stores!

The Odyssey Bookshop- https://www.odysseybks.com/

Amherst Books- https://www.amherstbooks.com/

Fireside Chat: Entangling Lives

Locating Early American Women’s History in the Built Environment

with Marla Miller

May 23, 2022

In this talk, Marla Miller takes the audience through a virtual tour of 40 Acres, while talking about the lives and the work of women who lived in the Porter-Phelps-Huntington house.

Bridging the Past and Present:

Entangled Lives: A Conversation on Women and Work at the PPH House in the Past and Present

with Marla Miller

June 16, 2021

Below is the recording of Professor Marla Miller’s discussion with Professor Karen Sánchez-Eppler about Miller’s new book Entangled Lives: Labor, Livelihood and Landscapes of Change in Rural Massachusetts. This was the first installment of PPH’s 2021 speaker series Bridging the Past and Present made possible by a grant from the Bridge Street Fund, a special initiative from Mass Humanities to enable open access to local histories.

Notes

[1] For more on this project, see Jacob Remes, “Marla Miller on her new book, Entangled Lives,” http://www.lawcha.org/2019/12/12/marla-miller-on-her-new-book-entangled-lives/; and The Page 99 Test, https://page99test.blogspot.com/2020/02/marla-r-millers-entangled-lives.html

[2] See Marla Miller, “Reflective Practice in Action,” presidential column, Public History News (National Council on Public History) Vol 40 No 2 (March 2020), 1+, which draws in turn on Rebecca Conard, “Facepaint History in the Season of Introspection,” The Public Historian , Vol. 25, No. 4 (Fall 2003), pp. 9-24 as well as her article “Public History As Reflective Practice: An Introduction,” The Public Historian, Vol. 28, No. 1 (Winter 2006), pp. 9-13; and Robert R. Weyeneth (on “pulling back the curtain” on public history practice), “What I’ve Learned Along the Way: A Public Historian’s Intellectual Odyssey,” The Public Historian Vol. 36, No. 2 (May 2014), pp. 9-25

[3] This and below from Karen Patricia Heath, “Chamberlain, Samuel V,” American National Biography Online, May 24, 2018.

[4] Heath, “Chamberlain.” In coming years Chamberlain would work with Henry N. Flynt on Frontier of Freedom: The Soul and Substance of American Portrayed in One Extraordinary Village (Hastings House, 1952)

[5] See Marla R. Miller, “Introduction,” Cultivating a Past: Essays on the History of Hadley, Massachusetts (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2009), 15; and Clifton Johnson, “The Tribulations of Founding a Farm Museum,” Old-Time New England 23, no. 1 (July 1932): 3-16, quotation, 6.

[6] M.A. DeWolfe Howe, Boston Landmarks (Hastings House, 1947); Behold Williamsburg: A Pictorial Tour of Virginia's Colonial Capital (Hastings House, 1947).

[7] Huntington joined the CSM Nominating Committee in April 1935, elected Corresponding Secretary in November 1936; He presented his own research on “The Honorable Charles Phelps” at the meeting of February 1937. See Publications of the Colonial Society of Massachusetts, Vol 32, Transactions 1933-37, pp. 308, 425, 441.

[8] “Journey to Hadley, 15 May 1948,” Publications of the Colonial Society of Massachusetts, Vol 32, Transactions 1933-37, p. 128.

[9] Huntington, Forty Acres, 34.

[10] On the spinning wheel as an icon, see Beverly Gordon, “Spinning Wheels, Samplers, and the Modern Priscilla: The Images and Paradoxes of Colonial Revival Needlework,” Winterthur Portfolio, Vol. 33, No. 2/3 (Summer - Autumn, 1998), pp. 163-194, and Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, The Age of Homespun: Objects and Stories in the Creation of an American Myth (New York: Knopf, 2001), and Christopher Monkhouse, "The Spinning Wheel as Artifact, Symbol, and Source of Design," in Kenneth L. Ames, ed., Victorian Furniture: Essays from a Victorian Society Symposium (Philadelphia: Victorian Society of America, 1982), pp. 155-59; on clothmaking at Forty Acres and in Hadley, see Entangled Lives, Chapter Five. I hope to develop this contemplation further in an article growing from my talk “Memory matters: interpreting early American women’s artisanal labor in museums and historic sites” for the symposium “Text and Textile,” Yale University, May 2018.

[11] Much of that scholarship is available on this website: see https://www.pphmuseum.org/bibliography