Schoolgirl Art Needlework Samplers

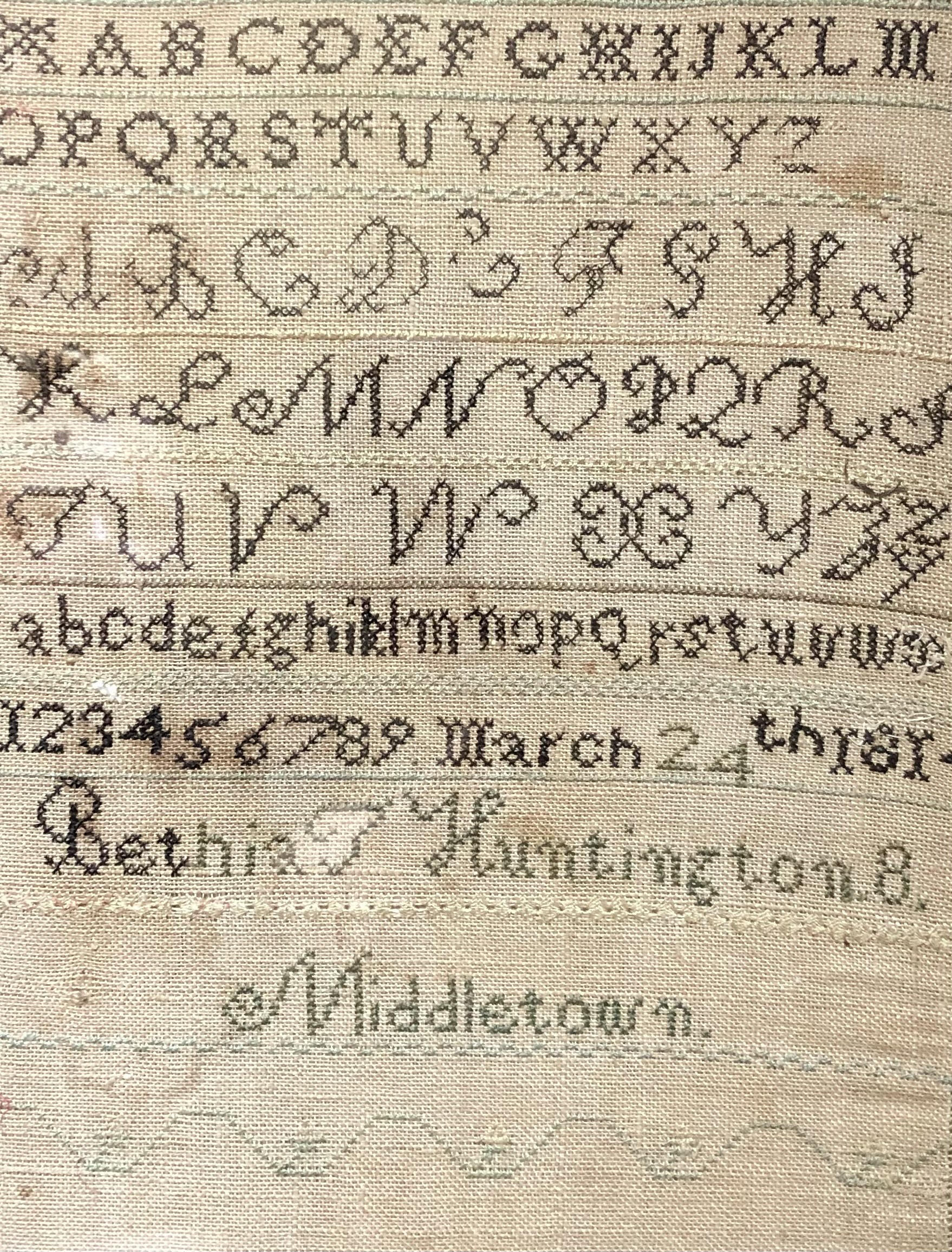

From the mid 18th to the mid 19th century, one of the most distinctive milestones in a girl’s education was the creation of a needlework sampler. A sampler - defined as a piece of needlework with various stitches- was part of the learning process for young girls to attain skills in sewing. A young girl would usually begin to sew around the age of six, often taught by her mother or another woman in the family. By the age of eight or nine girls would complete a first sampler; a piece usually composed of the alphabet, numbers, a Bible verse, or a quote about morality. The sampler piece above was created in 1814 by Bethia Huntington at just eight years old and serves as an excellent example to these preliminary works completed at a young age. The bottom line of Bethia’s work reads “Middletown,” a nod to when her father, Dan Huntington, moved the family from Litchfield to Middletown in 1809 for seven years while he was a minister at the First Congregational Church in Middletown. In 1816 they returned to Hadley after the death of the children’s grandfather, Charles Phelps.

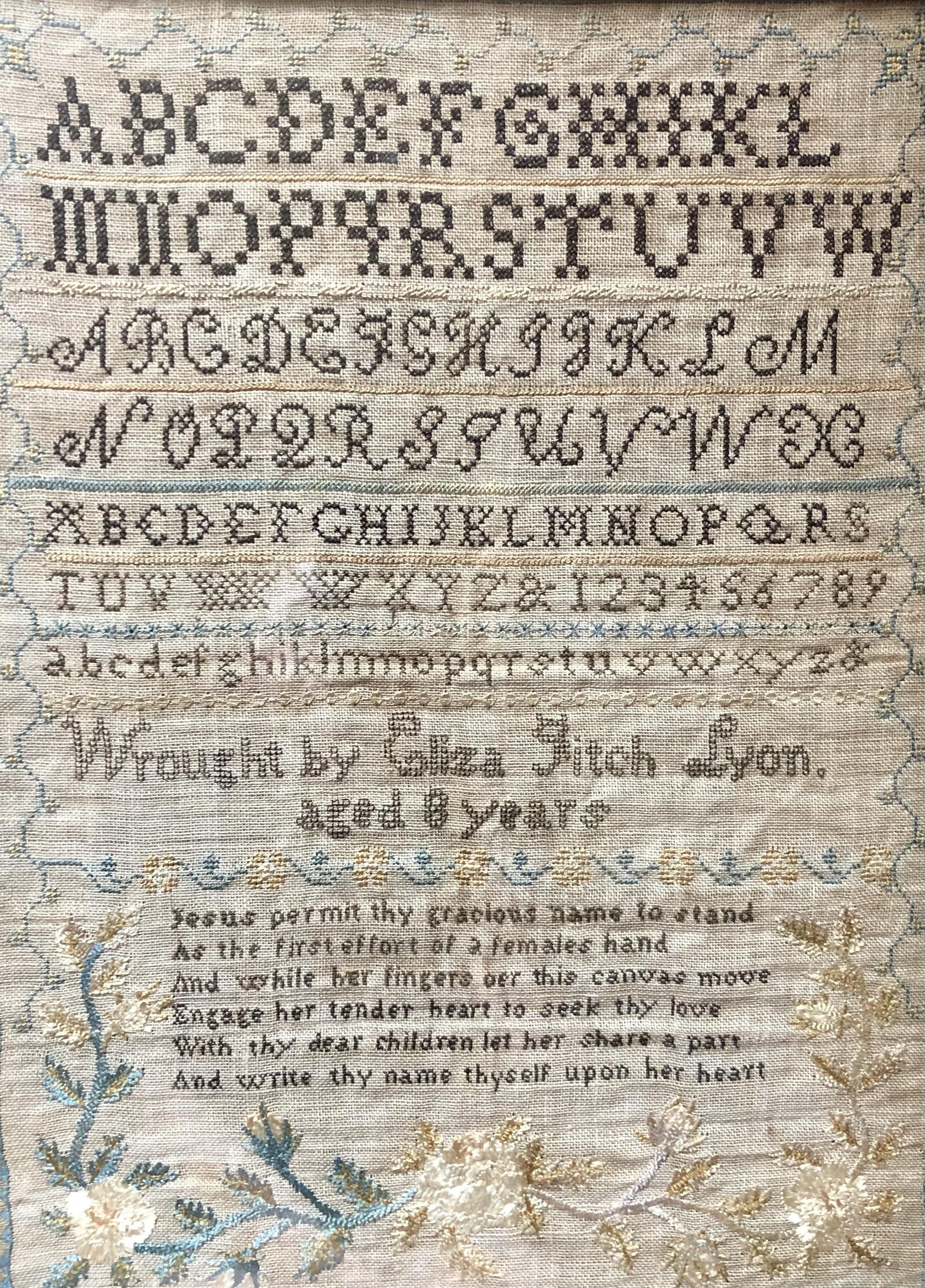

Another wonderful sampler in the Porter-Phelps-Huntington collection was wrought by Eliza Fitch Lyon at eight years old. Born in 1817, Eliza was the daughter of Maria Warner and Samuel Huntington Lyon. In 1827 she married Theophilus Parsons Huntington in Hadley, where they settled down to raise their three children. Eliza’s piece offers more insight into these initial samplers and is comprised of an alphabet with a supplemental Bible quote and botanical detailing. She takes her work to the next level with the inclusion of intricate floral patterns weaving throughout the piece. If you look closely under the cursive N through X, she experiments with fading blue thread into yellow. The detailing of this piece is quite remarkable regardless of age. Eliza includes numerous fonts and colors and has a keen eye for the details of the flora she includes at the bottom of the piece.

As skills in sewing progressed, plants, animals, or other objects copied from a pattern would sometimes supplement the writing. The execution of writing on samplers with increasingly more intricate designs and motifs provided practice for detailed stitching, along with the hope that producing works with such sentiments would foster virtue by publicly exhibiting morality and accomplishment. In the 19th century, the Pioneer Valley was known in the embroidery world for its “White Dove Style.” This style of sewing white doves emerged in the 1790’s and its popularity continued into the following few decades. Although there are no White Dove pieces at the Porter-Phelps-Huntington Museum, the collection contains several sewing samplers; one created by Bethia Huntington in 1814 (shown above) and another by Mary Huntington in 1826 when she was eleven. These works were displayed in homes with pride and as visual representations of their young daughter’s accomplishments.

By the time a young woman reached the age of fourteen it could be expected that she would have created several sewing samplers. Next would come a mixed media figurative scene, interchangeably referred to as either a pictorial scene or a silk embroidery. More than not these works incorporated other mediums such as watercolors into the needlework craft. For example, the piece above beautifully incorporates silk, watercolor, and satin. The plethora of mediums not only adds richness in texture but helps guide the eye through the depth of the harbor. Works as such tended to be very expensive to produce because they required several different skilled craftspeople to assist in creating the final product. Pieces as such not only showcased a young woman’s talent, but the aptitude to learn such craft implied the wealthy economic status of someone who could afford that kind of education.

When the Porter family crest was embroidered by Elizabeth Porter Phelps (circa 1760 - 1817), it was compiled from a painting on wood panel acquired by her mother, Elizabeth Pitkin Porter. The crest depicts five wings central to a plethora of vines and beautifully detailed birds of paradise. A coat of arms was a significant symbol for elite families in the Connecticut River Valley. Embroidering such was the height of needlework arts, as it created the “perfect form for displaying needlework, education, leisure, status, and family allegiance.” In this case Elizabeth may have been taught by her mother or other family members. Typically, such wonderfully elaborate embroidery would have been displayed in the parlor of the home for visitors to see. Although we know from the archives of her grandchildren that she likely commenced the project as part of her schooling at a young age, left it unfinished and returned to it in the final years of her life.

This article is based off previous research done by Mount Holyoke College alum, Ann Hewitt. Her work on needlework is a part of her larger research paper Becoming Accomplished: The Porter Phelps Huntington Daughters. Her preliminary research on needlework was further edited and continued by Museum Assistant Evelyn Foster.

Sources

Alice M. Earl, Childlife in Colonial Days (Norwood, MA: Norwood Press, 1899), 17.

https://www.pphmuseum.org/epp-needlework.

“Object of the Month Archive About.” Massachusetts Historical Society. Accessed July 26, 2021. https://www.masshist.org/object-of-the-month/objects/schoolgirl-needlework-2002-08-01.

Porter-Phelps-Huntington Family Papers, 1698 - 1968 (Bulk: 1800 - 1950).

“The ABCs of Schoolgirl SAMPLERS: Girls' Education and Needlework from a Bygone Era.” Milwaukee Public Museum. Accessed July 26, 2021. https://www.mpm.edu/research-collections/history/online-collections-research/schoolgirl-samplers.