Striking While the Iron’s Hot: The Trans-Atlantic ‘Adventures’ of Charles (Moses) Porter-Phelps

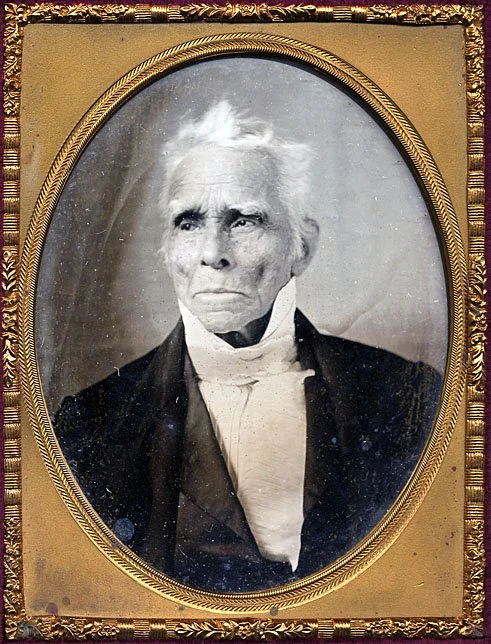

Phelps Farm, built in 1815, served as Charles (Moses) Porter-Phelps' (1772- 1857) escape from the hustle and bustle of Boston. He, the first son of Elizabeth and Charles Phelps, spent his youth in Hadley at Forty-Acres, before attending Harvard University as a young man. After graduation, he moved to Boston where he would try his hand at law, meet his to-be wife Sarah, and delve into a series of business deals that would largely work out in his favor. The wealth he amassed during his time in Boston paid for the construction of Phelps farm in the later years of his life. The large homestead, built right across from the Porter-Phelps-Huntington Museum, would serve as a home for several generations of the Phelps family, forever tying future family members with the sort-of work Phelps conducted.

Phelps’ first career in law ended when he closed his office in Boston in the summer of 1799, citing that the expenses to live in Boston far outweighed his salary, returning to Hadley to live with his family; during this summer he helped oversee some alterations to the home.(1) In 1800, he married his first wife Sarah Davenport, and decided to live in Boston once again. In the city, he would shift his career for the first of many times over his life. A business partnership with Edward Rand anchored his growing family in the city where Phelps experimented with merchant business from a wholesale on the No. 3 Cadman’s Wharf. Unfortunately, this would be a short-lived endeavor— in that same year, Rand died in a duel, permanently ending the arrangement. Soon after, Phelps strikes up a connection with William Belcher, a tradesman out of Savannah, Georgia, and for several years, the family’s income came from the ‘runs’ he and his partner did between ports in Boston and Georgia. Together, the men made their fortune in commodities cultivated by enslaved African Americans in the American South— goods like cotton, rice, and tobacco— selling such products to Northern American and European markets. During this time, Phelps occupied a store on the India Wharf in Boston, the city's headquarters of trade with international and domestic markets. Though a short-lived and tenuous peace had been met on the European continent, putting a brief pause on the Napoleonic Wars which ravaged the continent, Phelps and Belcher mutually dissolved their partnership— at least that is what Phelps attests to in his diary.(2) Although a number of factors likely contributed to this decision, it is possible that highly protective trade acts like the Embargo Act of 1807, which fully banned all American exportation to the European continent, contributed to the mutual end of affairs. (3)

Still, Phelps decided to send the rest of his stock of Havana Sugar, nearly $200,000 of goods in today’s currency (2024), to Rotterdam on the off-chance he may turn some profit in European markets in the summer of 1807. He’s only notified of the whereabouts of his shipment after he travels back to Hadley to be with his dying father— Charles Phelps Jr.. Phelps writes that by a ‘miracle of God,’ his shipment did in fact reach Rotterdam.(4) His business partner in Rotterdam, Mr. Cremer chose to hold on to the goods until the price inflated, and as a result, Phelps’ shipment sold for over $26,000—a little over half a million USD when adjusted for inflation— after deducting the price of freight. Cremers' decision to hold onto the goods further explains why Phelps cited confusion on the shipment's whereabouts and his surprise when he learned that the ship made it to the continent. He notes in his autobiography that this is a godsend to his business, and with some embargoes lifted by 1809, he returns to Boston with his family and begins to dip his hand into international trade once again. With this large sum of money, the family continued to live as an incredibly wealthy family, skirting the financial crisis many families went through. Most overseas businesses ceased in 1812 and goods produced within the United States became increasingly more expensive; while many families struggled during this time to afford necessities, the Phelps had a mass of wealth that would sustain them for several years, regardless of Phelps’ labor status.

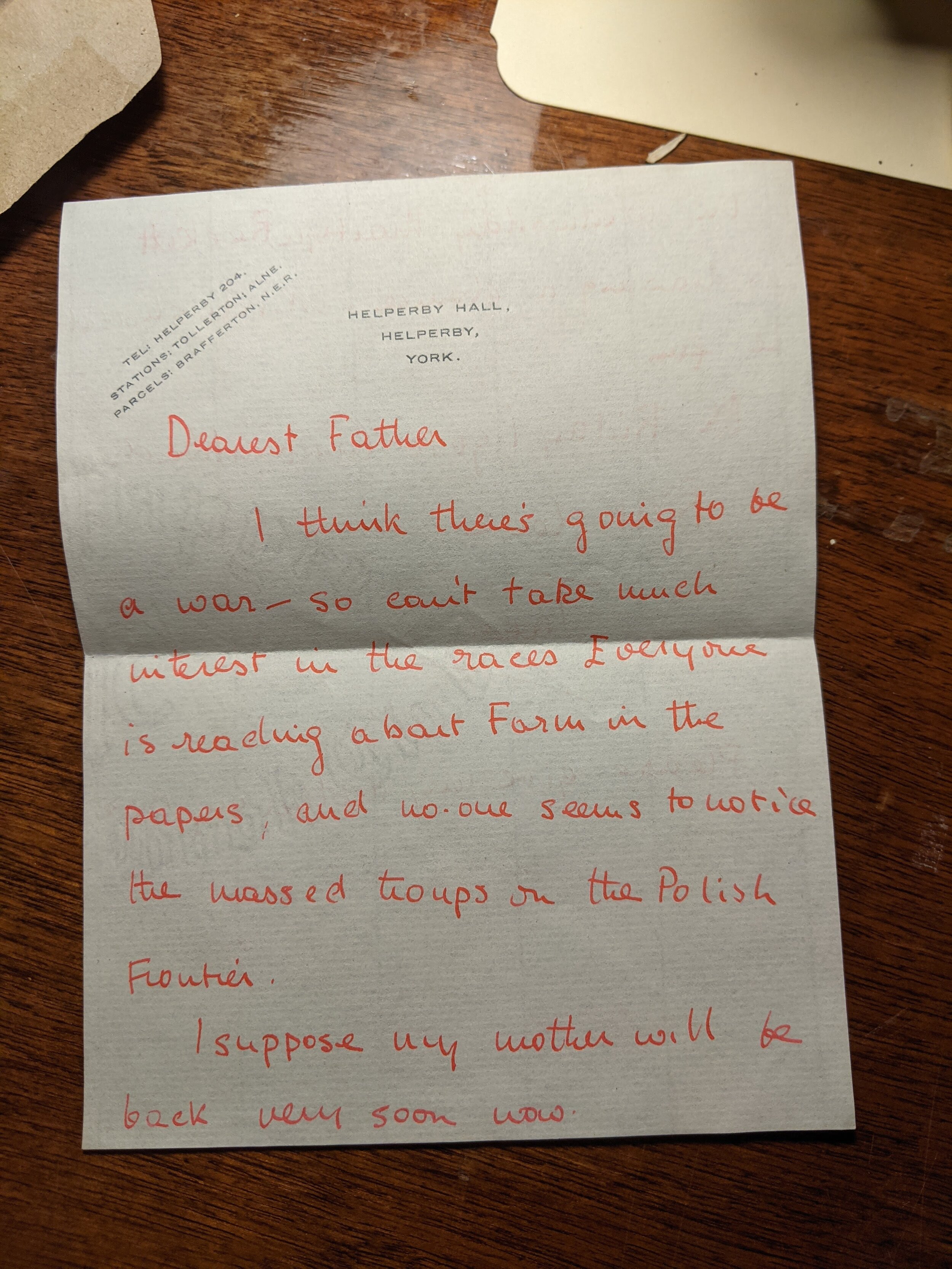

In the spring of 1812, America entered what Phelps calls a ‘useless’ war with Great Britain, the War of 1812, (5) during which all Trans-Atlantic commerce was suspended. (6) A letter sent to Phelps in 1812 discusses the complex geopolitical conflicts that drastically impacted trade. The writer warns Phelps of the various treaties that would alter the viability of trade with nations like Russia, France, and Britain.(7) According to Phelps, any trade that was occurring during this time had an air of militarism, as ships were under constant threat from the British Navy. Over the next few years, businesses like the Phelps’ would be pushed to seek out new markets internationally as the regular channels of commerce closed. His business would become chiefly connected to webs of trade in northern Europe, though specifically to the iron business in Gothenburg, Sweden.

One side of a draft letter to Charles (Moses) Porter Phelps which outlines various political conflicts in Europe that hindered the viability of trans-Atlantic trade, written from Hamburg on March 3, 1812. The writer (unintelligible) describes the benefits and drawbacks of trade with Sweden, particularly that though Sweden is still open to trading, the trade market is limited. By the end of the letter, the writer hopes that the ‘embarrassment to Commerce” will cease by the Summer— that market conditions will improve.

“My own business was now chiefly connected with the trade of northern Sweden, some of my shipment of that kind having been quite successful— and during the two coming years my business was almost wholly in that line. Indeed, during the war I kept quite a respectable wholesale and retail Iron Store on the Long Wharf.” [Phelps, 48]

Above is a deed of shipment, signed by Nicholas Myers, outlining a shipment of goods from Gothenburg Sweden, on May 9, 1812, to Charles (Moses) Porter Phelps in Boston. According to the deed, 2,284 bars of Swedish Iron and 102 bundles of Swedish Iron (weighing 40 tons) were shipped by John Cunnigham upon a ship called the Indian Chief to Phelps in Boston. The deed requests that Phelps pay $560 and 6 cents as a delivery fee, about 13,242.59 in today’s currency (2024).

A receipt of shipment dated May 8th, 1812 attests to this transition in trade, as some 2,285 bars of Swedish iron were transported from Gothenburg to Boston and delivered to Phelps.(8) A wholesale that he’d purchased on the Long Wharf in Boston was the headquarters of his business— a business, which, like the many other iron traders, took advantage of the market for iron available in accessible ports in Sweden. Such trade would become instrumental in the progression of industrialization into and through the mid-1800s.

By 1815, the U.S. was quickly returning to its once peaceful relationship with the European countries, as the Treaty of Ghent was agreed upon and signed in December 1814, officially closing the conflict on all fronts. The shift in geo-political relations once again resulted in a shift in economic relations, straining the viability of the Swedish iron trade with America. International trade was returning to a state of normalcy as blockades fell and markets were reopened. In Boston specifically, the prices of imported goods began to fall.(9) As a result, Phelps chooses again to shift his career, leaving the mercantile business for good and entering banking, moving into a position as a cashier for the Bank of Massachusetts.(10)

“At this period the commerce of Europe and America was fast resuming its usual peaceful relations. Men bred to this business and well established in it, might indulge reasonable hopes of success— but the untrained- desultory shipper must now expect as a matter of course to pocket more losses than gains— and the truth of this was fully verified in the business in which I allowed myself to engage, small as it was, for the two succeeding years, such being the aspect of things, I was induced to the close of the year to accept the office of Cashier of the Massachusetts Bank…” [Phelps, 61]

Banking at any level was a privilege of the time, something reserved for only the upper echelons of society, and was a career well suited to his class and status. He remained in Boston for a few more years before moving back to Hadley and building Phelps Farm.

The choices Phelps made during this unsteady time in American history allowed his family to escape the financial burdens that befell the general population of early Americans. From trading in Southern American goods to trading Swedish iron, he relied on his business to consistently sustain his family’s high-class lifestyle during some of the most tumultuous financial times of the early 19th century, building a generational fortune for the Phelps family and a large farmhouse to go with it. Still, his initial ‘runs’ of cotton, tobacco, and sugar up the eastern seaboard would implicate the family’s wealth in the continued enslavement of African Americans in the southern portions of the United States and the Caribbean— prolonging systems of enslavement throughout the country even after slavery ends in Massachusetts.(11) And, his later decision to import iron to the United States made him one of many merchants of iron who played an essential role in furthering the industrialization of the U.S. through the early 1800s— a process that would have harrowing implications for labor relations and the health of the climate into the early 20th century and today. Therefore the decisions Charles (Moses) Porter Phelps made during his life chiefly connected the family to a web of commerce which, while sustaining his family’s status, would be influential in determining the lives of generations of Americans to come.

End Notes

(1) Phelps, 20

(2) Phelps, 32-33

(3) The Embargo Act of 1807 came as a response to French and English naval policies which dictated that all vessels found trading with England and France respectively were to be seized.

(4) Phelps, 37

(5) The American War of 1812 being an expansion of the ongoing Napoleonic Wars (1793-1819) in mainland Europe. Trade warfare resulted from this expansive war, with trade blockages often halting imports/ exports out of entire countries for extended periods. Piracy was commonplace and ships, and the cargo they held, were frequently confiscated.

(6) Phelps, 47

(7) The signature on the letter is unintelligible

(8) Shipping Receipt, Porter-Phelps-Huntington Family Papers (MS 1148). Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries.

(9) Adamson, 71

(10) Phelps, 61

(11) Slavery legally ends in Massachusetts between 1782-1783.

Sources

Adamson, Rolf. “Swedish Iron Exports to the United States, 1783–1860.” Scandinavian Economic History Review 17, no. 1 (January 1969): 58–114

Phelps, Charles (Moses) Porter. Autobiography (1857) Porter-Phelps-Huntington Family Papers Box 10 Folder 21 Amherst College Archives and Special Collections

Shipping Receipt, Porter-Phelps-Huntington Family Papers (MS 1148). Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries.

Letter Addressed to Charles (Moses) Porter Phelps, Porter-Phelps-Huntington Family Papers (MS 1148). Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries.