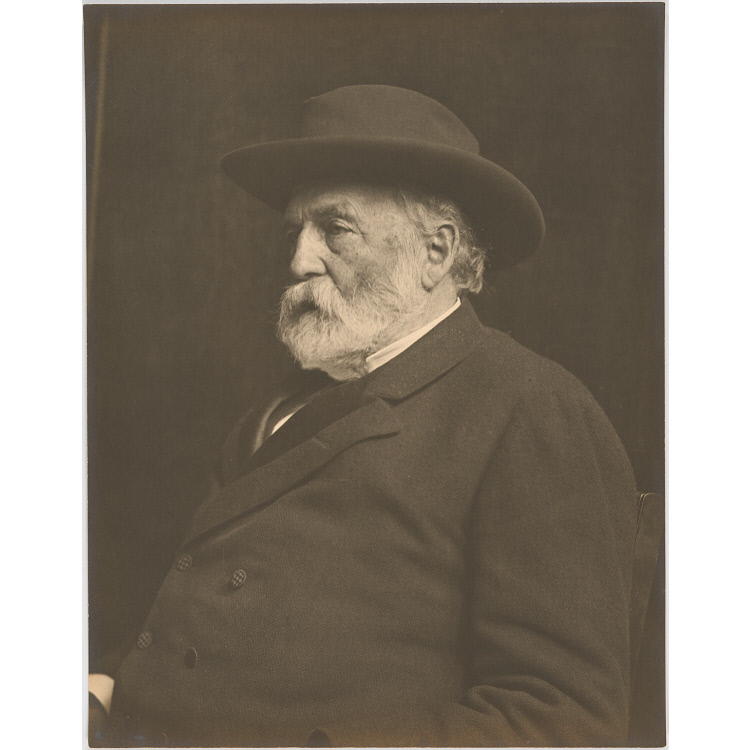

Charles "Chippy" Phelps Huntington

The death of a child is a story that loses none of its bite over time. It is hardly an unusual occurrence, but the blow never softens, each consecutive tale of child mortality just as tragic as the first. Nowadays, generally speaking, most healthy children are able to reach adulthood. However, this wasn’t always the case in the past. In the first half of the 20th century, there were innumerable threats looming over children. Between 1900 and 1950, scarlet fever, measles, polio, the Spanish flu epidemic, and the sudden availability of automobiles were all great concerns—and that’s on top of two world wars. The world was, and is, a dangerous place for children, and the particular brand of tragedy that is child death did not pass over the Huntingtons.

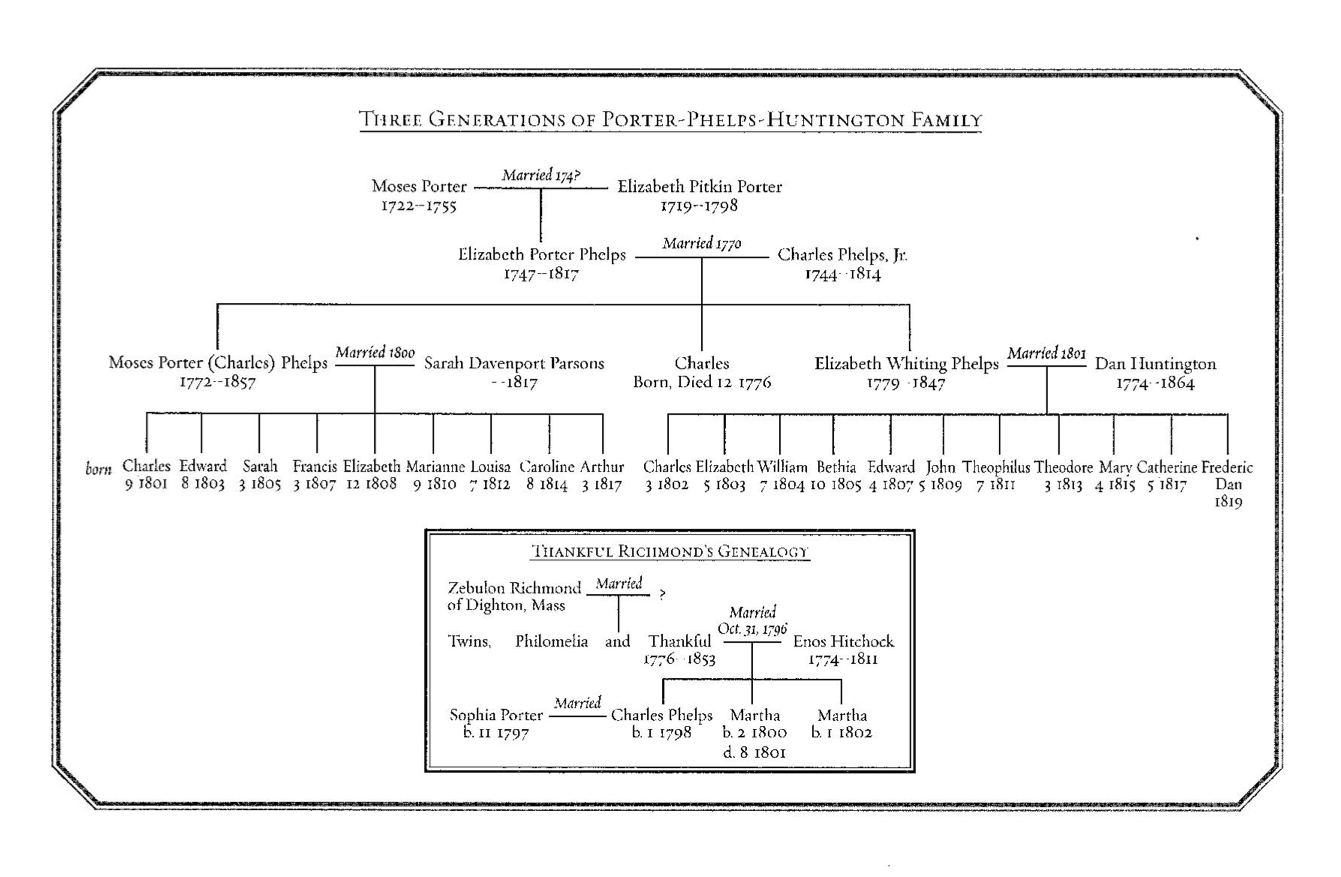

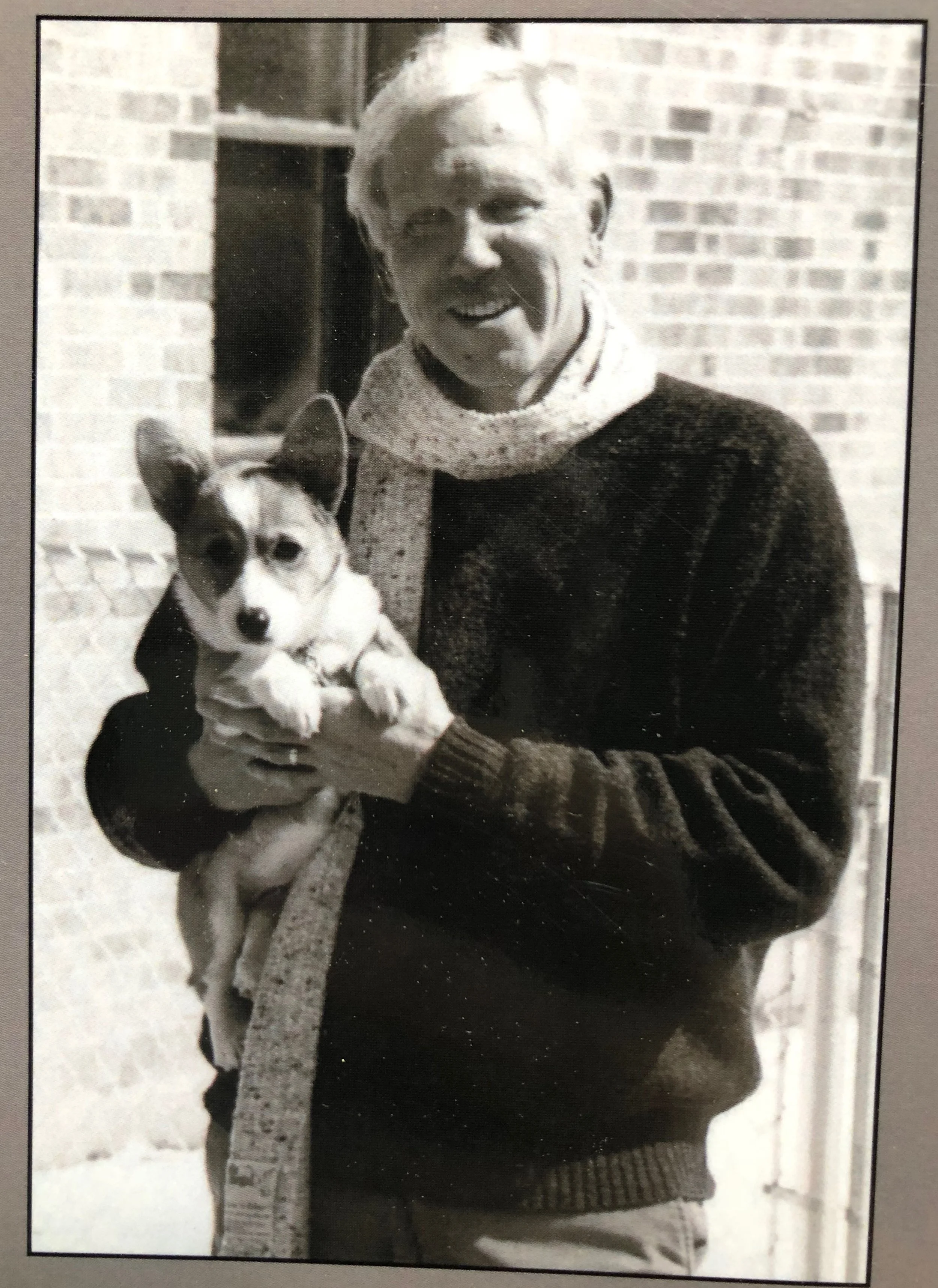

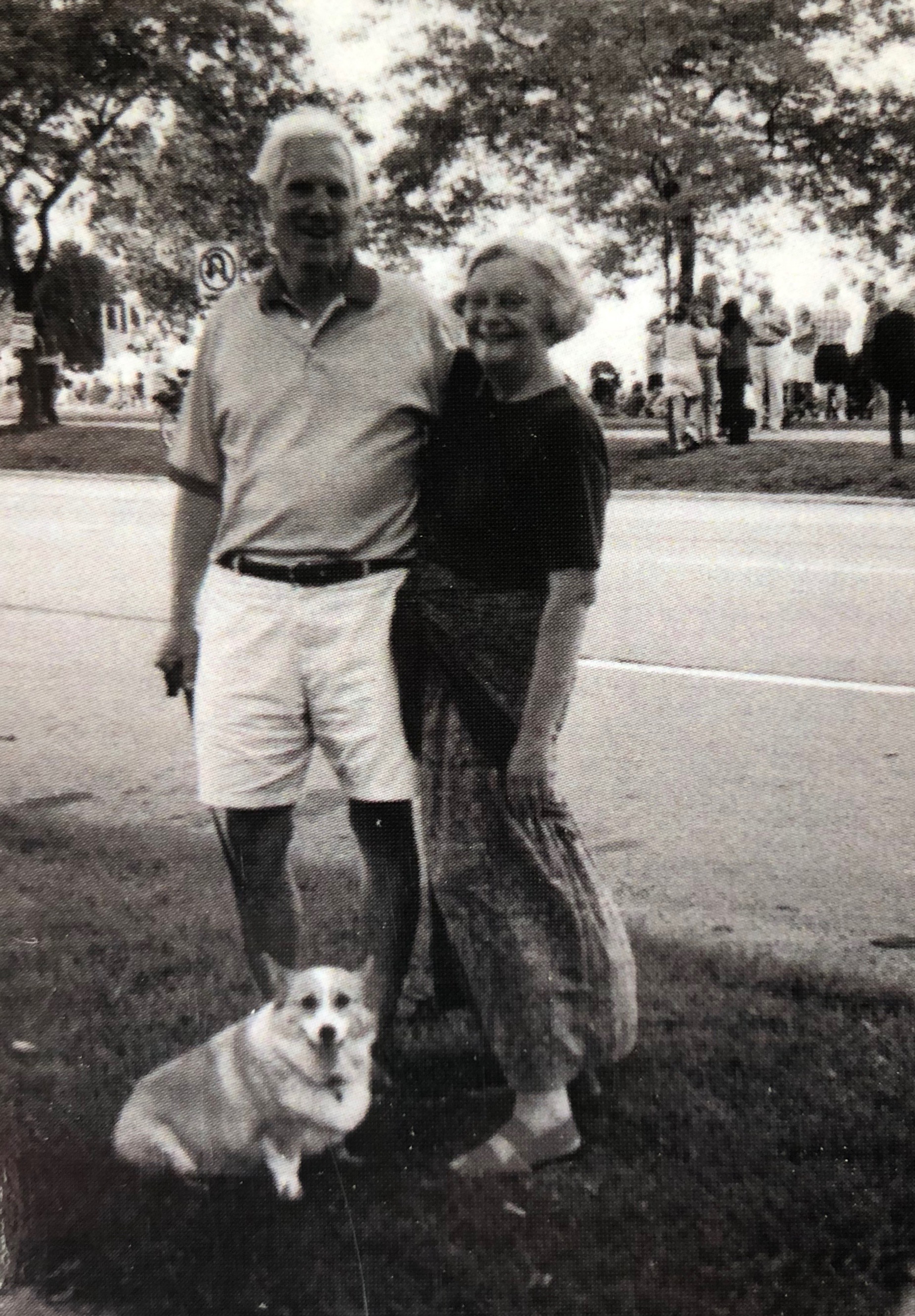

Charles Phelps Huntington, nicknamed “Chippy,” was the youngest son of Lona Marie Goode and Michael Paul Huntington. He was born on May 13, 1928, in Delaware. This photograph, along with the treasure trove of Chippy’s childhood scrapbook, is a recent acquisition of the museum. The scrapbook is full of wobbly letters and the sorts of odds and ends that children find important taped into the pages—a ball from a BB gun, a movie theater ticket, a Macy’s advertisement, a valentine. It paints a vivid picture of a sweet and cheerful boy; his scrapbook holds a membership for the ‘Vacation Reading Club’ showing how many books he’d read, perfect attendance certificates, report cards (he had very good grades), a little homemade bicycle license, and all kinds of notes and letters. He exchanged several Valentine’s Day cards with a girl called Georgia Shelley, who wrote him a thank-you note that he taped into his scrapbook. There’s a thank-you card from an aunt to whom he wrote a get-well card while she was hospitalized. His eldest brother also wrote family letters that addressed him directly, and the little personal details are quite charming (‘Chippy, how are the doggies?’).

About a third of the way into the scrapbook, though, the haphazard, cheerfully misaligned scraps of paper stop very abruptly. There is a report card, with columns for the teacher to fill out every five weeks; it is completed up through week 15, where Chippy’s school absences (the first of his life, if the perfect attendance certificates stuck into earlier pages are to be believed) are marked in the ‘½ days absent’ section. Then, the scrapbook picks up again with pages and pages of lovingly arranged baby photographs, pictures of Chippy as an infant, a toddler, a child. Chippy’s faltering cursive does not reappear. Tragedy had struck: one day in 1937, as Chippy was walking to school, he was hit by an automobile and died. He was nine years old.

After her son’s death, Chippy’s mother, Marie, took over the scrapbook to memorialize his life. She seems to have kept absolutely everything: old telegrams and greeting cards congratulating Marie on his birth; baby shower notes; cheery birthday cards from Chippy to each of his parents. A personal favorite—a Mother’s Day card on which Chippy wrote a poem: ‘To my mother,’ it says, ‘When you smile, then life is sunny. / When you speak I know good cheer / When you love it is forever / You are treasured Mother dear. From Charles P.H.’ The big green scrapbook is simultaneously the record of a young child’s life as he documented it and the grief of a mother at her young son’s death; both an archive and a memorial.

There is a poem, printed on a piece of stiff paper, at the end of the scrapbook; Springtide, by Phila Butler Bowman. It is unmarked but for the name of the poet in Marie’s handwriting at the bottom, and one highly significant alteration: in the second to last line, ‘Someday, we shall see her face again,’ Marie has crossed out ‘her’ and written ‘his.’ With this change, the poem reads:

Springtide

I know I shall find my violets

Each year in the same old place,

So I grieve not that snow or a silence fall,

Knowing the hidden grace.

For love strikes down with a deeper root

Than any woodland thing.

Someday we shall see his face again,

And our hearts will say,

“It is Spring!”