A week of Preparations for the Huntington Family Thanksgiving

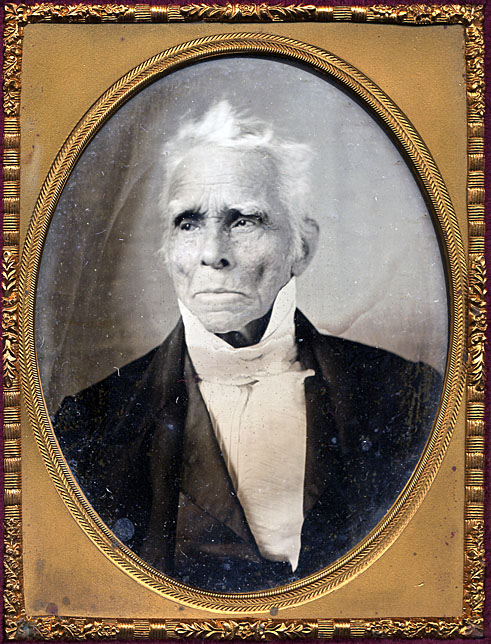

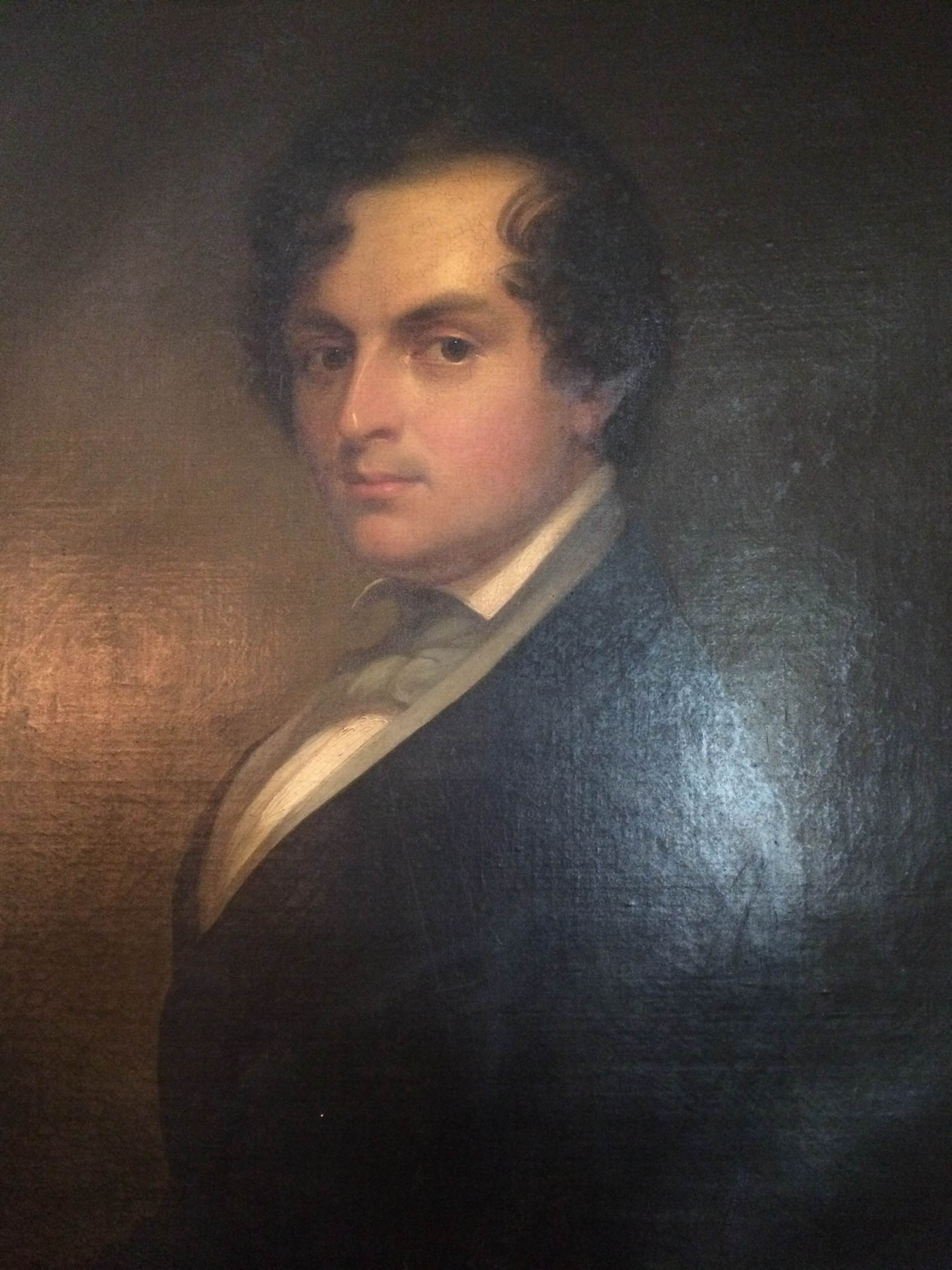

Theodore G. Huntington

Theodore Huntington, the eighth child of Dan and Elizabeth Huntington's eleven, was born March 18, 1813 in Middletown, Connecticut. At the age of three, he moved with the family to Hadley. Shortly before his death in 1885, Theodore wrote a collection of reminisences he called "Sketches of Family Life in Hadley". Below are excerpts from his writings describing the extravagant Huntington Family Thanksgiving and its week-long preparations.

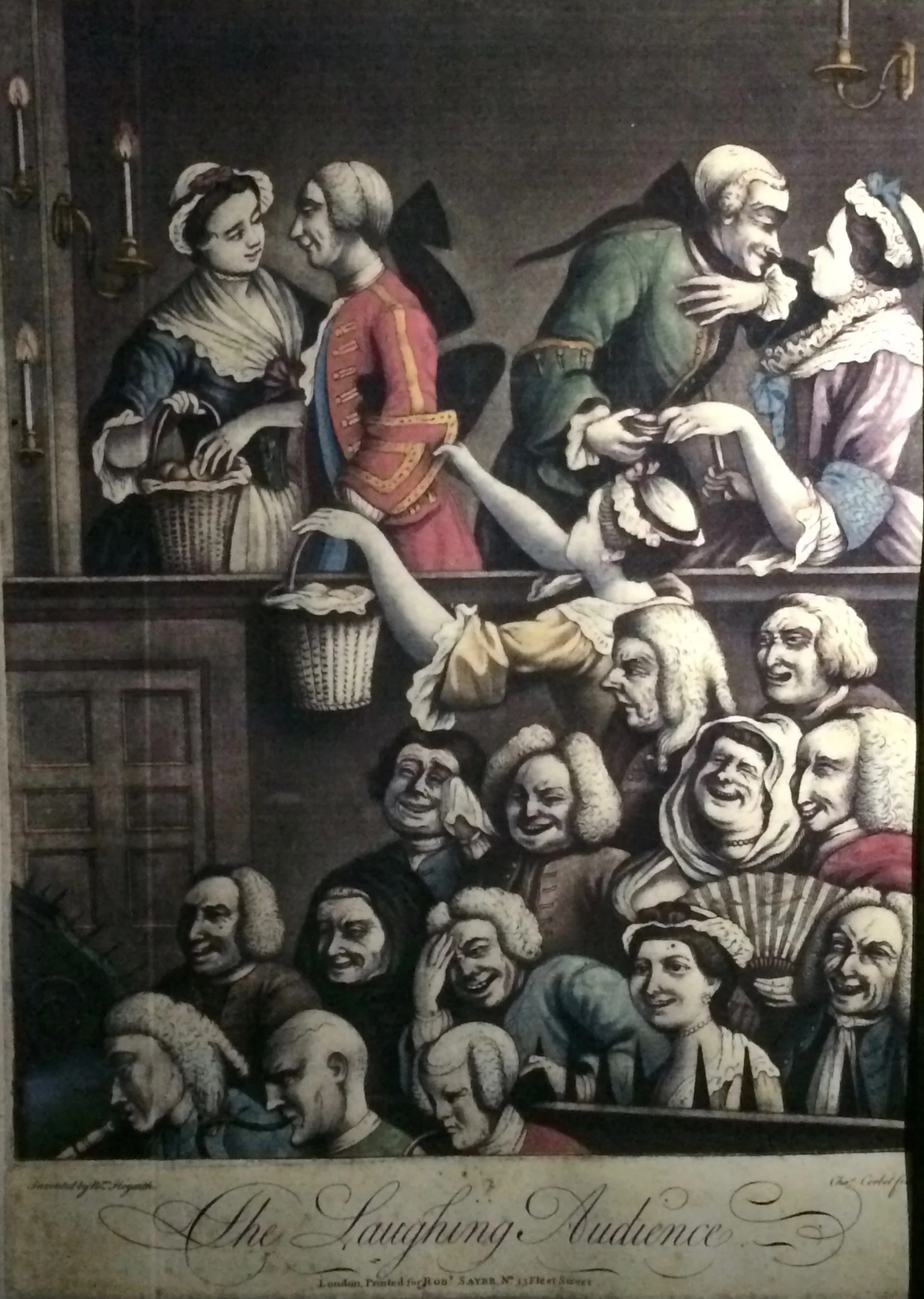

MONDAY:

“Monday was devoted, of course, to the weekly washing and nothing must interfere with that. Tuesday was the great day for the making of pies of which there were from thirty to fifty baked in the great oven that crackled and roared right merrily in anticipation [of the rich medley that was being made ready for its capacious maw.” (34)

1799 Kitchen

TUESDAY:

"Two kinds of apple pies, two of pumpkin, rice and cranberry made out the standard list to which additions were sometimes made. Then in our younger days we children had each a patty of his own. These were made in tins of various shapes of which was had our choice, as well as of the material of which our respective pies should be composed.” (34)

1797 Kitchen

WEDNESDAY:

“Wednesday was devoted to chicken pies and raised cake. The making of the latter was a critical operation. If I mistake not it was begun on Monday. I believe the conditions must be quite exact to have the yeast perform its work perfectly in the rich conglomerated mass. In due time the cake is finished. The chicken pies are kept in the oven so as to have them still not at the supper. The two turkeys have been made ready for the spit; the kitchen cleared of every vestige of the great carnival that has resigned for the last two days and there is a profound pause for an hour or two before the scene opens.” (34)

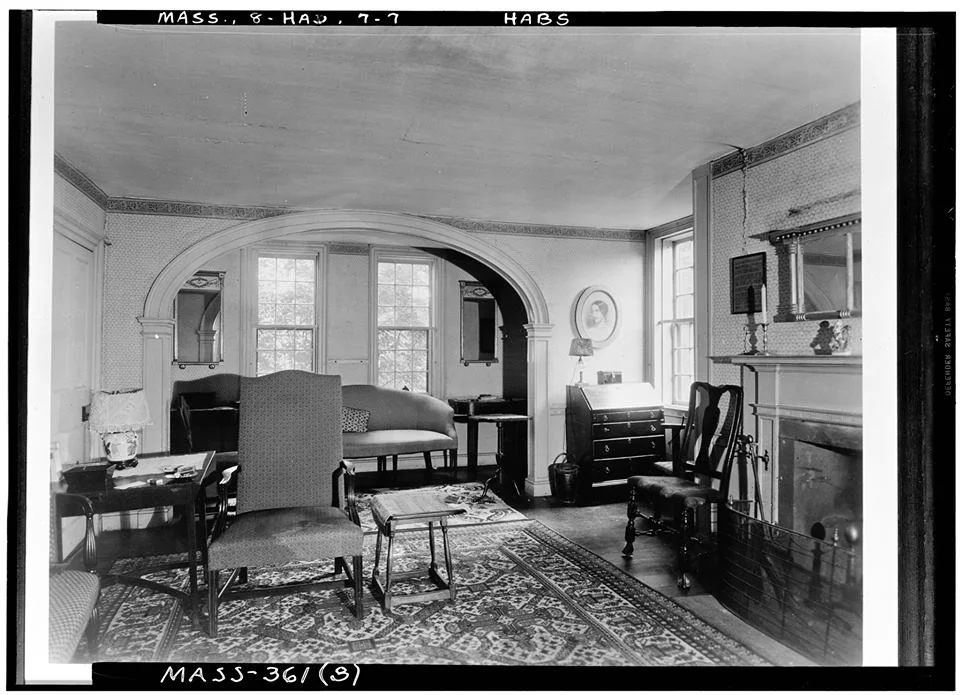

Dining Room

THURSDAY:

"I remember once quite a sensation was produced in the little crowd because brother Theophilus lost his balance and for want of a chair to break his fall, sat down on one of the smoking hot pies! After cooling and sorting, the precious delicacies were put away into the large closets in the front entry of hall which the foot of tho small boy was not permitted to profune. “(34)

“There was still a more primitive way of roasting turkey and one which was resorted to sometimes when our family was at the largest. Room was made at one end of the ample fireplace and the turkey was suspended by the legs from the ceiling where was a contrivance to keep the string turning, and of course, with it the turkey. On the hearth was a dish to catch the drippings and with then the meat was occasionally basted. The thing is accomplished much more easily now, but at an expense I imagine in the quality of the work. “ (35)

To read more of Theodore's recollections, follow the top link below to his sketches as well as the link to Theodore at the Amherst Archives in the bottom link!

http://asteria.fivecolleges.edu/findaids/amherst/ma30_odd.html#odd-tgh