Graphing the Gardens

The landscape at the Porter Phelps Huntington Museum is just as much an historical resource as its structure and interiors, with each of its many acres having its own ledger of alterations and varying usages. Though histories of the grounds can be harder to uncover than written ones, the above maps, detailing the grounds and in particular the North Garden, provide a partial record of the evolution of the grounds and exhibit the intricacy and diversity of the floral and plant life at the Museum.

The grounds themselves underline the privileged nature of the family: not only was it the second-largest property in the area with ~600 acres of land under the control of a single family, but it was unique in its creation and maintenance of gardens for largely aesthetic pleasure.

As the first map above exhibits, the grounds in the early years of the house were almost entirely functional, which is perhaps unsurprising. As the Pioneer Valley History Network’s website, The Revolution Happened Here, writes, “Prior to Morrison’s tenure at Forty Acres, Elizabeth had described gardening as sporadic and casual.” With the consolidation of land and wealth in the family and the stewardship of the aforementioned Morrison, a Scottish ornamental gardener, the garden became a focal point of the landscape.

During the Revolutionary War a Scottish prisoner of war by the name of John Morrison was captured and indentured to Charles Phelps and came to work at Forty Acres. Due to the strain put on local farms by conscription requirements, farmers were allowed to use captive soldiers for labor on their land, and the Phelps were no exception. Elizabeth’s diary mentions the arrival of “one of the Highlanders” who was quickly discovered to be a trained ornamental gardener and charged with the creation and maintenance of the gardens. This marked the beginning of the peak years of the garden: in Ruth Ann McNicholas’s thesis, she writes that “These years from 1770 to 1814 also represent the period when the grounds and gardens were in their prime.”

As the second and third maps show, the North Garden was replete with functional and aesthetic plantings alike, from apple trees to annuals to more practical plantings like squash, corn, asparagus (or ‘Hadley grass’), and various other vegetables. Its central focus was a circular bed of Scotch Roses, a celebrated rosa spinossima.

With the death of John Morrison in 1815 the gardens quickly deteriorated. In a letter to her daughter, Elizabeth Porter Phelps writes that “‘Our garden looks like a forsaken place…a great variety of pretty flowers which if there was anybody to dig the ground and arrange them properly would appear well… Beets, onions, here are very few, mustard small, through neglect.’”

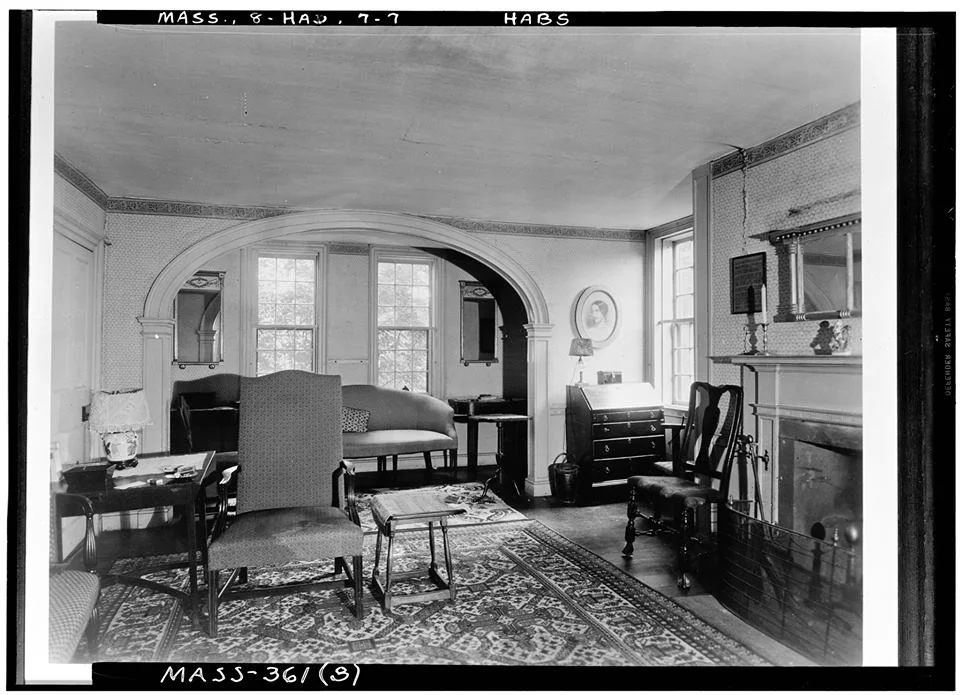

Though the garden suffered after the death of John, it seems to have remained very much appreciated by the next generation of inhabitants, Elizabeth and her husband Dan Huntington. His elegant words paint a picture of the garden, pictured above, during his time and its scents and bounties. He writes:

“‘The roses, the seringas (sic) and the honeysuckle stand around the doors and windows, in all their fragrance, and the house at night is filled with the odour. The garden with its appropriate fruits and flowers, standing in regular order, shows us not only what we are by and by to expect, but begins already to afford us its choice delights, in the asparagus…pepper grass, lettuce and radish – not forgetting the green currants, hanging in luxuriant clusters.’“

Their iteration of the garden can be seen in the map above, which shows that half of the North Garden had been plowed for perhaps more utilitarian purposes than before. Even so, the Reverend mentions a “Mr. Woods” that had been doing the gardening, suggesting that the family retained their penchant for a private gardener and had the means to do so.

The penultimate map, which displays the grounds under Frederick Dan Huntington and Hannah Dane Sargent from 1865-1910, describes “overgrown planting beds” and seems to suggest the restoration of the North Garden to its former size.

The sixth and final map, wrought by Catherine Sargent Huntington, offers a more detailed account of the plantings in the North Garden. Though the flora is different from that which is listed in the prior map, the layout seems similar and there is agreement over the apple trees surrounding the garden.

Though there are no maps to reflect it, after this period it seems that planting at the house became more reserved. Ruth Ann McNicholas writes that “Plantings of lilacs and sweet mockorange around the house were controlled and sparse, framing and setting off the detail of the architecture, which, in many places, is quite intricate.” This is perhaps a reflection of the tastes of Dr. James Huntington, the founder of the Museum, who sought to highlight the history of prominent (male) inhabitants of the household rather than its long past as a productive farm, as can be seen in his transportation of the Corn Barn and removal of other functional out buildings.

With the grounds comprising an integral part of the Porter-Phelps-Huntington Museum, their future and maintenance has become a central question of the Foundation’s mission, particularly with a changing climate and the presence of invasive species. Thanks to an Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) grant, the Museum has begun work with Miguel Berrios, a Landscape Architect and Certified Arborist to create a Pollinator Conservation Activity Plan. The program, funded through the Natural Resources Conservation Service division of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, will develop a plan to revitalize the local biodiversity and create a habitat for pollinators, like honeybees, that have been affected by the alteration and destruction of their environment. Mr. Berrios’s plan will mark a new chapter for the grounds at PPH, one that will hopefully recreate the environment that Elizabeth Porter Phelps, Dan Huntington, and other family members described with such affection.

Sources:

“John Morrison: Highlander, POW, Gardener, Tippler.” Revolution Happened Here. Accessed July 14, 2021, https://www.revolutionhappenedhere.org/items/show/33.

McNicholas, Ruth Ann. Porter-Phelps-Huntington House Museum: Restoration of Historic Grounds. UMASS Masters Thesis, 1985.