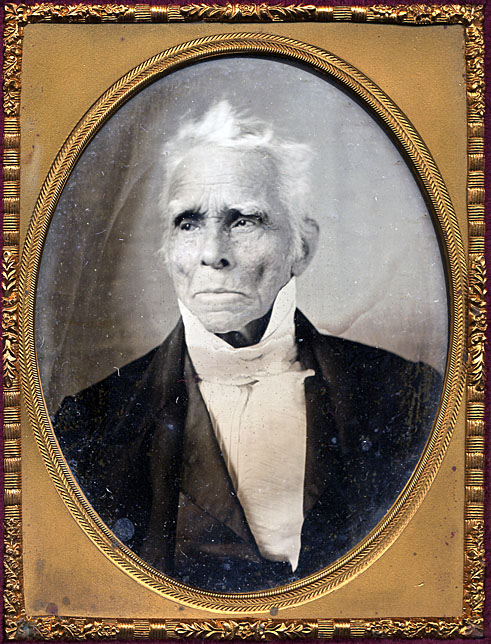

Charles (Moses) Porter Phelps (1772-1857)

Charles (Moses) Porter Phelps was born August 8, 1772 to Charles Phelps and Elizabeth Porter, starting the third generation to have lived at Forty Acres. He spent his childhood at the family homestead in Hadley, leaving in the Spring of 1780, when only seven years old, to live and attend school in Northampton. Charles and Elizabeth were intent on Porter (nicknamed at the time) succeeding to Harvard. In 1784, Porter continued his education in Hatfield where he lived and studied at Reverend Joseph Lyman’s, a grammar school emphasizing the study of Latin and Greek. A week after his fifteenth birthday, Porter set off for Cambridge to enroll at Harvard College. There he diligently kept an account book following his father’s admonitions, also recording the latest urban fashion and pastimes taking place in Boston. He corresponded with his parents and siblings thorough letters, influencing his sisters Betsey and Thankful with the extravagance of fashion and material items in Cambridge. The archives hold a letter in which Betsey references her new silk stockings that Porter bought for her – the same stockings which Jane Austin had written her sister about, lamenting her inability to afford such luxury just four years earlier (Carlisle 131). Porter also sent Betsey a mandola for her to practice music, this instrument still sits on the sofa in the Long Room of the museum today.

While at Harvard, Porter was greatly influenced by the philosophers and theologians who expressed ideas for the liberation of the Calvinist Congregation and writers such as John Locke and Jean-Jacque Rousseau. This thinking amongst other things, may have caused Porter to switch his belief to the new Unitarian Philosophy in the early 19th century. Porter graduated Harvard second in his class in 1791 and changed his name to the more formal Charles Porter Phelps. Upon being awarded his master’s degree (also from Harvard) he gave a valedictorian speech in fluent Latin. Although today this would have been seen as a grand accomplishment calling for admiration, no mention of praise is seen in diaries or letters from the family. From Charles and Elizabeth’s Calvinist perspective, admiration of that sort would have been discouraged. Looking at Calvinism from today’s point of view we can suspect this admiration would have been seen as encouraging vanity. In his autobiography, Porter writes of his sensitive struggle with self doubt. A struggle that carried on throughout his life. He writes,

This shrinking section has attended me thro life—and tho it may sometime have been productive of good, yet, having so often become its victim, I have no doubt that on the whole, it has proved baneful and disastrous. [i]

Could this self doubt have been an after effect of the lack of approval and emotional support from his Calvinist parents?

In 1792, Porter headed to Newburyport to study and board under Theophilus Parsons, a prominent lawyer of the 18th century. Interestingly, John Quincy Adams had studied under Theophilus Parsons just four years earlier between 1787 and 1788. As well as being an esteemed lawyer, Parsons was also a strong advocate of the Massachusetts State and federal constitutions. Parsons, with the help of John Hancock, formed three amendments for the Constitution as well as the Bill of Rights. Porter stayed in Newburyport until a few months after the expiration of his clerkship there in January 1795. During his residence he had come to know Sarah Parsons, niece of his mentor Theophilus Parsons. Sarah had lived with her grandmother in Boston and upon her death moved to Newburyport in 1794, bringing the two closer together the months before Porter was admitted to the bar and left to open his own practice in Boston. By 1795, the two were engaged to be married. In June of that year a party was organized for a group of young people from Newburyport to attend an ordination in Haverhill. In his memoirs, Charles confesses that he did not know what controlled his action, but he invited another woman to accompany him—leaving Miss Parsons to try to find a seat with her Uncle’s family. He says, “what demon of folly—or madness—took possession of me I know not...and soon I felt that every attempt to apologize only exasperated the bitterness of the insult.” [ii]. His self-deprecation had caused him to shrink from any public display of his affection for Sarah whom he “most desired to propitiate and honor” [iii]. After the ordination party, Charles and Sarah grew cold to one another, leaving his sisters and mother to grow in fear that he would not find love—his best chance seeming to have gone. In May 1796, Charles Phelps (Sr.) and Elizabeth Phelps visited Boston as Charles (Sr.) was representing the general court. While there, Elizabeth, upon meeting up with her son expressed a wish to visit an old friend living in Newburyport (knowing well that Sarah would be there). Charles Porter was to do his mother a favor by driving her in his chaise. Could this have been a covert plan by Elizabeth to rekindle the spark her son and Sarah Parsons once had? Porter took his mother’s intrusion happily and resolved to “make a final effort, either to restore myself to her forfeited favor or on the other hand to ensure the extinction of all my hopes by a repeated – and what in this case would inevitably prove to be – an irreversible rejection.” The plan worked successfully and the couple were once again awaiting their betrothal.

While in Boston, Porter’s parents, Charles (Sr.) and Elizabeth, encouraged him to settle back home in Hadley and Porter felt his law office was not giving him the kind of success that ought to keep him from Forty Acres. In April of 1799, he closed his office and spent that summer helping outline the new renovations his father wanted for Forty Acres to both expand the property and keep his architectural design contemporary. The family, in hopes of Charles and Sarah moving in after their wedding the following Spring, started work on a third floor for the couple. This renovation is what changed the profile of the house from a pitched roof to a gambrel roof (an architectural design that many elite homes in Boston were favoring at the time). However, after these renovations to Forty Acres in 1799, the couple chose to stay in Boston where Charles formed a business partnership with Edward Rand—leaving the third floor unfished as we see it today. Together Charles and Rand formed a merchant business from No.3 Cadman’s Wharf until the summer of 1801.

In the late afternoon of Saturday June 13th at Dorchester point, just south of Boston, Rand stood, gun raised, in a duel against a Mr. Miller. Supposedly, Miller had challenged Rand on account of a “lady from Rhode Island”. Porter writes, “Rand had the first fire and missed and that then Miller took deliberate aim”[iv]. Porter was called upon to retrieve his partner’s body and helped to bury him in the Granary burying Ground late that night. Everyone directly involved in the duel skipped town, for duels had been illegal acts since 18th century. Porter continued his export business until 1816 when he began his political career as a Boston Representative to the State Legislature. By the end of that year he had received a large profit from his buisness and chose to use the money to build a house on his share of the ancestral Hadley property. This house still stands as Phelps Farm today. To great sorrow, Sarah contracted Typhous fever and passed away on the move to her new home. Her cousin, Charlotte Parsons came to help a devastated Charles in bringing up his and Sarah’s five children. Porter and Charlotte grew close and married in 1840, parenting four more children—many did not survive youth. Charlotte died in 1830 and in 1833 Porter married for his third time to Elizabeth Judkins. He continued running the family farm he had built for he and Sarah and gained status as a Hadley lawyer and selectman.

Charles Porter Phelps died December 22, 1857 at the age of 85 a man of respect; honored and and trusted by this Hadley Community. He had served ten terms as as Hadley Representative in the legislature and senator of the Hampshire district and was acknowledged by his neighbors as a man of high principle and clear judgment.

Notes:

[i] Phelps, Charles (Moses) Porter. Autobiography 1857 (p.19)

[ii] Phelps, Charles (Moses) Porter. Autobiography 1857 (p.17)

[iii] Phelps, Charles (Moses) Porter. Autobiography 1857 (p.20)

[iv] Phelps, Charles (Moses) Porter. Autobiography 1857 (p. 35)

Sources:

Phelps, Charles (Moses) Porter. Autobiography (1857) Porter-Phelps-Huntington Family Papers Box 10 Folder 21 Amherst College Archives and Special Collections

Carlisle, Elizabeth Pendergast. Earthbound and Heavenbent: Elizabeth Porter Phelps and Life at Forty Acres, 1747-1817. Scribner, 2004.

The Phelps Family of America, and their English Ancestors, with Copies of Wills, Deeds, Letters, and Other Interesting Papers, Coats of Arms and Valuable Records. Volume II Pittsfield, MA: Eagle Publishing Company, 1899.

Search these links to find more about Theophilus Parsons or about John Quincy Adam’s time as his student!

http://www.harvardsquarelibrary.org/biographies/theophilus-parsons/

https://archive.org/stream/bub_gb_HJEOAAAAYAAJ#page/n5/mode/2up/search/Phelps%2C+Charles