Strange Unheard of Things: Catharine Huntington’s Writing and Correspondence with Gladys Huntington

Currently filling the corn barn at PPH are stacks, packages, and bundles of letters written to or by members of the Huntington family. The postdates attest that rarely a day went by without any given Huntington penning a letter to inquire after someone’s health, share an amusing anecdote, or simply catch up, a testament to the family’s proclivity for the written word. Their literary pursuits were not limited to these daily communications; however, many of the family members were published authors, poets, or playwrights. Arria Huntington (1848-1921) wrote plays and memoirs, Ruth Gregson Huntington (1849-1946) published a number of short stories and poems, and in the next generation, Constant Huntington (1876-1962) served as the chairman of the London branch of G. P. Putnam’s Sons Books from 1906 to 1953. He and his wife Gladys were heavily involved in the London literary scene, corresponding and dining with such litterateurs as James Joyce, Desmond McCarthy, and Harold Nicolson.

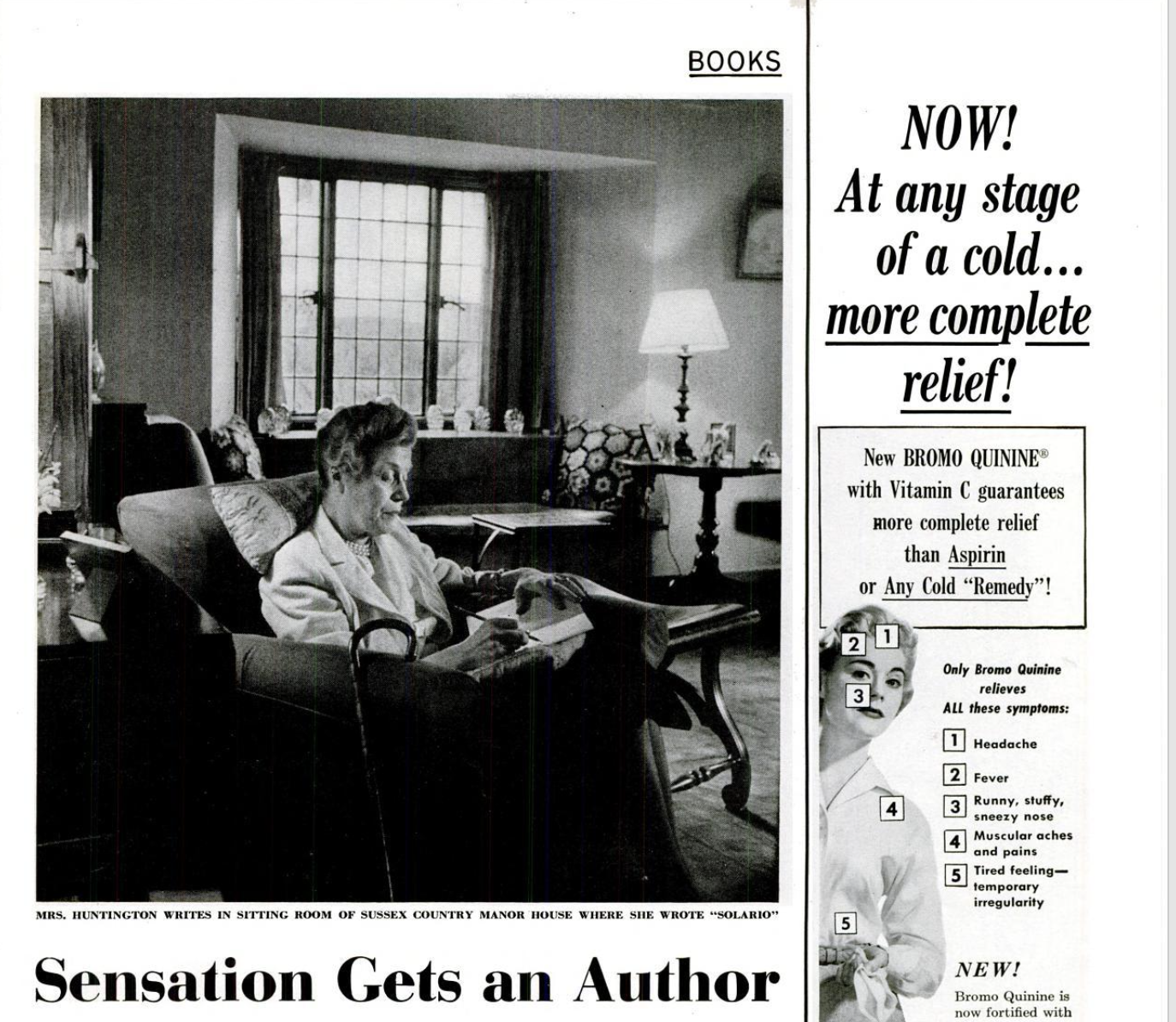

Of all the family members, Gladys Parrish Huntington (1887-1959) arguably found the most literary success, although she would only be recognized for it over three decades after she was revealed as the author of the bestselling 1956 novel Madame Solario. This revelation came quietly a few months after the anonymous novel’s publication; Life Magazine reported in its March 18, 1957 edition (which itself cites an earlier article in the London Express that had revealed Gladys’ identity) that “the author was an elderly literary gentlewoman...living in the backwater of Kensington.” Yet, speculation continued for decades. Acclaimed British author Mary Renault, in an interview with The American Scholar in 1970, claims Madame Solario to be “one of the finest novels of our century,” going on to say: “After many inquiries in the publishing world, I learned the author was called Constance Huntington.” Not quite. A 1992 French mystery novella entitled Qui a Écrit Madame Solario? made the bizarre claim that Winston Churchill was the author. Bernard Cohen’s extensive research, published in the French newspaper Libération in 2009, is widely credited for definitively solving the not-so-mysterious mystery, although the novel had been published with Glady’s name on the cover as early as the 1980s. The real mystery is why no one noticed.

Easily regarded as her magnum opus, Madame Solario drew high praise from writers and critics, including comparisons to the prose of Henry James, Edith Wharton, and E. M. Forster. Over half a century following its publication, the allure of the story persists, inspiring a 2012 French film adaption of the provocative tale of incest and social scandal, as well as translations into seven languages. The novel’s consideration of such taboo topics has often been speculated to be the reason for which Gladys chose to conceal her identity as the author upon the initial publication. She published under the name Gladys Parrish as early as 1915 with her novel Carfrae’s Comedy, published by Putnam while Constant was at its head. Her play Barton’s Folly was produced a decade later, receiving an overall unenthusiastic critical response. A packet of reviews of the play’s production we came across consistently categorized it as a disappointment, but recognized the sign of a talented new voice. “The play had that “something” which justified its performance by The Three Hundred. It lay in the dramatist’s sense of the interesting complexity of human relations. Though inexpert, confused, and full of bugbears, Barton’s Folly is the work of an imagination. I found it often absurd, but never dull,” wrote leading literary critic Desmond McCarthy, who would go on to become a close friend of Gladys. She did not publish or produce again for over 30 years, perhaps taking the time to hone her skill and voice as a writer. These efforts were well spent, for two of her stories were subsequently published in The New Yorker in 1952 and then again in 1954 under the name G.T. Huntington, a vague enough stylization of her married name to obfuscate both her gender and any connection to what she previously published. Whether or not this was her intention is unclear, for the runaway success of Madame Solario a few years later established Gladys, by this point in her 70’s, as a brilliant new literary voice.

Tucked away in a packet of correspondence between Gladys and her sister-in-law Catharine Huntington (1887-1987) was a letter from the latter to the former, enclosed in an envelope together with a short story and a photograph of herself. Catharine humbly cautions her sister-in-law about her writing, “It is only a fragment- it may amuse you for a moment- at all events it gives pleasure to send to you.” If Gladys was the literary icon of the family, Catharine was the theatrical. She was involved with the Peabody Playhouse, the Brattle Theatre, the Tributary Theatre, and the Poet's Theatre, juggling the many titles of actress, producer, director, and manager. Further, she helped to found the Boston Stage Society, the Provincetown Playhouse, and the New England Repertory Theatre. Her integral role in New England theatre lasted for over six decades and earned her a Rodgers and Hammerstein Award in 1965, as well as formal recognition from Governor Michael Dukakis and Massachusetts State Legislature in 1985 for her contributions. Before finding her niche in the world of theatre, it seems that Catharine dabbled in writing as so many Huntingtons had before her.

The letter in question is dated only as far as August 11th, although given its subject and contents, it can be dated to 1917, as World War I intensified in Europe. This would have been prior to Catharine’s serious involvement in New England theatre. The letter expresses the perspective of a 30-year-old schoolteacher trying to find her place in the world, seeking a sense of purpose in the war efforts and speaking longingly of lives vastly different from her own. “I long so much to go to France, to serve in the trial… Without any very definite prospect and still uncertain whether it would be right to leave home- I began to prepare,” Catharine writes. She goes on to tell Gladys of her concentrated efforts to this end: enrolling in a nursing course run by the Red Cross, motor driving lessons at the YWCA automobile school, a course in Ford machinery. She practiced her French with a kindly Miss Hough on a bench in the Boston Public Garden and took on nursing shifts at the Massachusetts Homeopathic Hospital, the building of which today houses Boston University’s School of Public Health. Evidently, her studies paid off, for within a year she had left her job teaching at the Westover School and travelled to France, where she would serve as a nurse’s aid until 1920 in the Wellesley Unit of the YMCA. Contemplating this next chapter in her life, she writes, “I don’t know whether I am in a great mess or gloriously on my way- somewhere.” Catharine concludes her letter by signing off with that same note of desperate ambiguity: “Dearest Gladys- do write more- your life seems so clear and lovely- mine so confused and full of strange unheard of things.”

“One Afternoon”, the short story Catharine sent along, reflects many of these same sentiments in its protagonist, Laurencina, an aristocratic young woman disillusioned by the allure of high society and feeling unmoored in her life. The piece takes place in the U.S Virgin Islands over nine pages, largely composed of dialogue between Laurencina and her rejected suitor, Charles Durrain. Her writing takes a Whartonian interest in the discontents of the upper class, balancing afternoon social calls, high tea, and literal high brow-edness (“The hair grew thick off his high forehead,” Laurencina observes of Durrain) against Laurencina’s consuming desire for something more that she can neither identify nor attain.

“Charles-” she broke out, in the midst of something that he was saying, “I am so dissatisfied with my life- You have known me a long time- Why is it that I seem to be accomplishing nothing? I feel that I could be so wonderful, do so much, and here I am day after day.” The thoughts that had crowded her mind for so long- now seemed to have left her. After all, she could not express them.

“Don’t be dissatisfied,” Durrain was saying. “Think of your influence in the family here- and then your father! There is a reason for being of use. What would he do without you?” He spoke in the voice of a teacher.

“Yes,” Laurencina answered in a low tone, “I must not be dissatisfied.” And then her passion broke out again. “You are a man, and cannot judge fairly. There is your work at the Embassy, and your visits here and there, moonlight rides-”

Catharine’s keen awareness of the different prospects available to men and women comes through in Laurencina’s reticence to accept Durrain’s dismissive response. Perhaps she is thinking of her own position, uncertain as to whether or not to leave her family behind in the States and travel to Europe in search of a life of more consequence. Catharine does strike out on her own, but the fictional Laurencina does not; further down the page, she takes up knitting, performing in the act an acceptance of Durrain’s ideas about the role of women. As the story concludes, Laurencina continues her performance of contentment at family dinner that night:

“Charles Durrain asked to be remembered, Papa,” Laurencina said.

“Oh, he was here- again. I should like to see him. You ought to marry him, Laurencina.”

Laurencina moved her plate a little. She felt very tired. Edith was speaking in her kind, high voice.

“Oh, Laurencina is so hard to please.”

Laurencina made an effort and smiled a little.

There the story ends, with Laurencina more desolate than before following her failure to find sympathy and understanding in Durrain. The manuscript bears marks of the editing process, presumably by the hand of Catharine herself, crossing out phrases and inserting others. Perhaps the piece is a work in progress, though it seems unlikely that Catharine had any intent to publish or further refine her work. Her writing style is rather unpolished, aiming for the Whartonian undertones her sister-in-law captures so evocatively, but not quite hitting the mark. She tends to tell rather than show, and it’s all just a bit cliché and melodramatic: “In the narrow mirrors as she passed- Laurencina saw her face- it seemed to her that a strange, beautiful woman looked at her sorrowfully.” Nonetheless, Catharine’s goal of momentary amusement for her audience was well met in the brief glimpse she provides into the drama of Laurencina’s personal life and psyche. Catharine crafts a compelling narrative of her protagonist’s complicated relationship with Durrain and struggle to assert herself within the societal constraints that would limit women to marriage and household duties. In the thousands of letters we’ve yet to read, perhaps we’ll come across Gladys’ response to Catharine, and discover her reactions, encouragements, criticisms, or praises of her sister-in-law’s work.

Sources

Bastek, Stephanie. “Neglected Books Revisited, Part 2.” The American Scholar, Phi Beta Kappa, 11 Aug. 2020, theamericanscholar.org/neglected-books-revisited-part-2/.

Cohen, Bernard. “Madame Solario Tout Un Roman.” Libération, Libération, 7 Nov. 2009, www.liberation.fr/culture/2009/11/07/madame-solario-tout-un-roman_592310/.

“G.P. Putnam's Sons Records, 1891-1937: Rare Book & Manuscript Library, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.” G.P. Putnam's Sons Records, 1891-1937 | Rare Book & Manuscript Library, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, The University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, archives.library.illinois.edu/rbml/?p=collections%2Ffindingaid&id=943&q=&rootcontentid=90949.

Joyce, James, Gilbert, Stuart, & Ellmann, Richard. (1966). Letters of James Joyce (New ed., with corrections..). Viking Press.

McCarthy, Desmond. “Drama Inexperienced and Expert.” The New Statesman. 20 December 1924.

“Sensation Gets an Author.” Life, 18 Mar. 1957, pp. 125.