"You would find a bombing a very disagreeable experience" - Correspondence from Early WWII

With COVID-19 and other tumultuous events, those of us living in 2021 are familiar with the feeling of living on the precipice of a momentous time in world history while ordinary life seems to continue on, unaffected. Through selections from correspondence included in the Constant Huntington Papers, generously donated by Katherine Urquhart Ohno in 2019, it is interesting to explore how Constant & Gladys Huntington’s friends and adolescent daughter experienced and discussed the run up to and beginning of World War II.

Constant, Gladys & Alfreda Huntington at a wedding, June 8, 1939.

The Huntingtons’ primary residence was in London when Britain declared war on Germany on September 3, 1939 after German forces invaded Poland. All of these letters were written in August or September 1939, and can provide insights into the beginning of the war for Britain, as portrayed by ordinary Britons, uninvolved in any decisions surrounding it.

You can click on each letter to read it larger or see a more complete transcript.

On August 3, 1939, Leo Myers, a friend and fellow author, wrote to Gladys expressing his thoughts on the “causes of the approaching war” and commenting on the weather.

It also illustrates for me a particular idea of mine: [viz?], that the world is governed more by pique, rancour, feelings of slight, the "inferiority complex", etc. much more than is realized. The future historian, certainly, will analyze the causes of the approaching war in [?tare/tone?] terms. Collectively, as well as in their representative ruling figures, Italy & Germany are going to war more out of wounded vanity, & rancour(e) rather out of any legitimate sense of injustices to be redressed or even avenged. The wrongs have been committed, the injustices have existed, but they are going to war largely in order to satisfy pettier spites.

[…]

I hope it hasn’t rained all the time, for that does make such a difference when one is living in Hotels. I am feeling so water-logged and heavy. It will be nice to see you again. I am working; & it has become a habit; and I’m not good for anything else now. I do hope this letter (dull as it is!) will reach you in Stockholm all right.

One imagines war as an all-consuming force in life, yet Leo here easily moves from discussing warfare to the weather, and calls his letter dull.

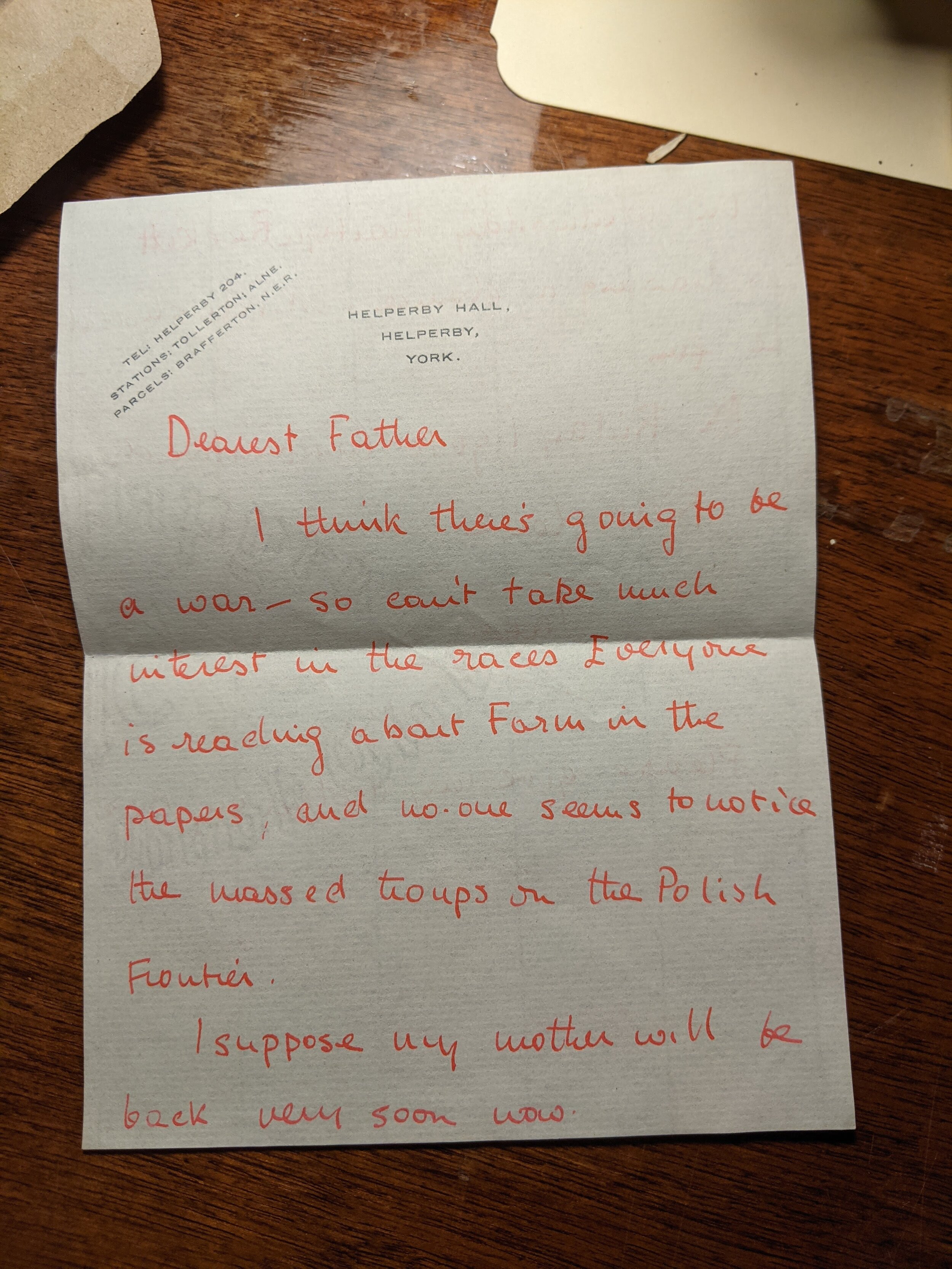

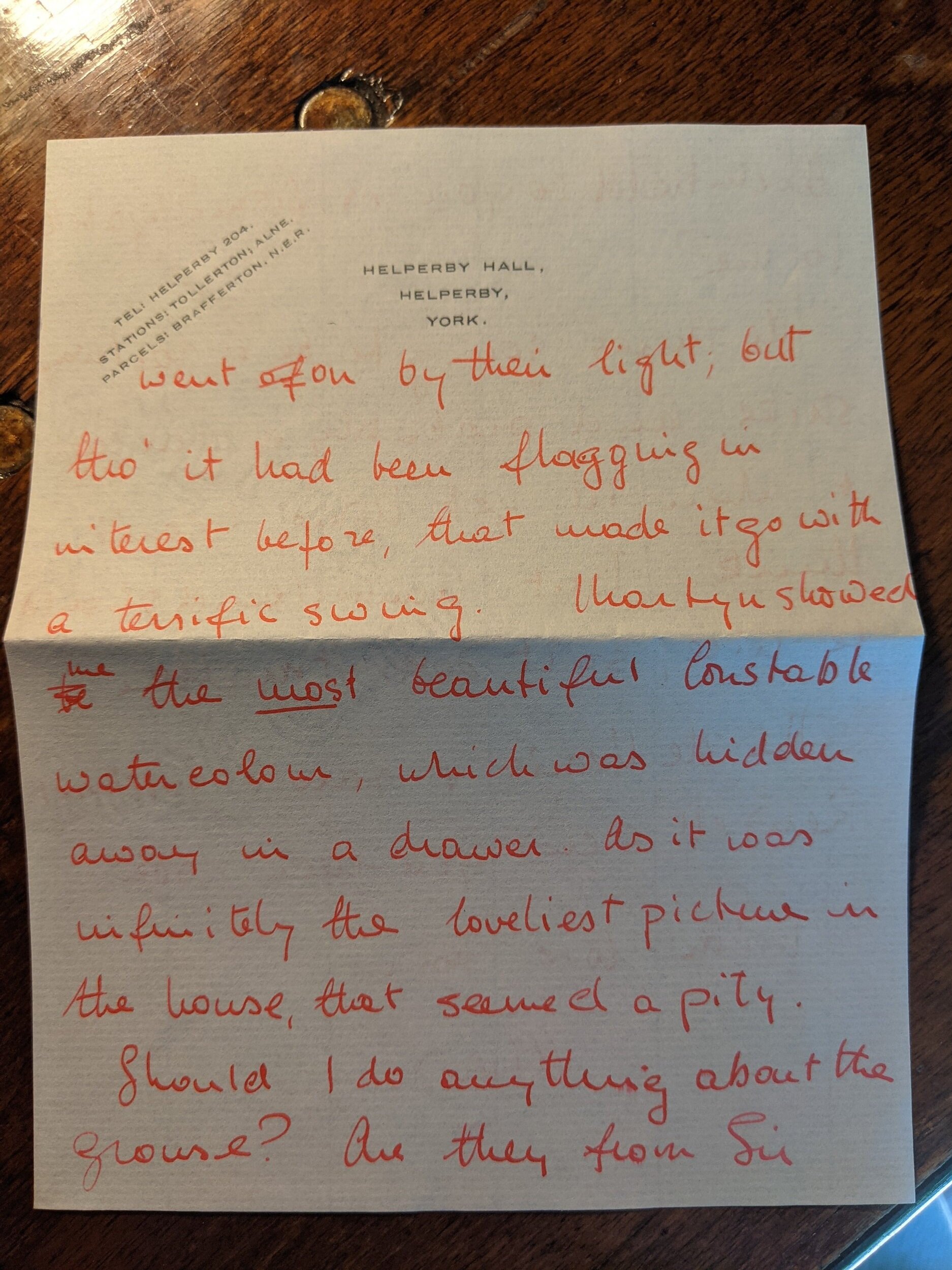

At the beginning of this otherwise ordinary letter about daily life to her father, Constant Huntington, written August 24, 1939, Alfreda Huntington (signing off under her nickname “Jane” - short for her first name, Georgiana) mentions that she “[thinks] there’s going to be a war”—a prescient assessment just 12 days before war was declared.

Dearest Father,

I think there’s going to be a war - so can’t take much interest in the races Everyone is reading about [Farm] in the papers, and no-one seems to notice the massed troops on the Polish Frontier.

I suppose my mother will be back very soon now.

On Wednesday Martyn Beckett is having a dance - which should be fun.

On Friday I go to Cumberland.

Best love -

Jane

Please give my mother my love

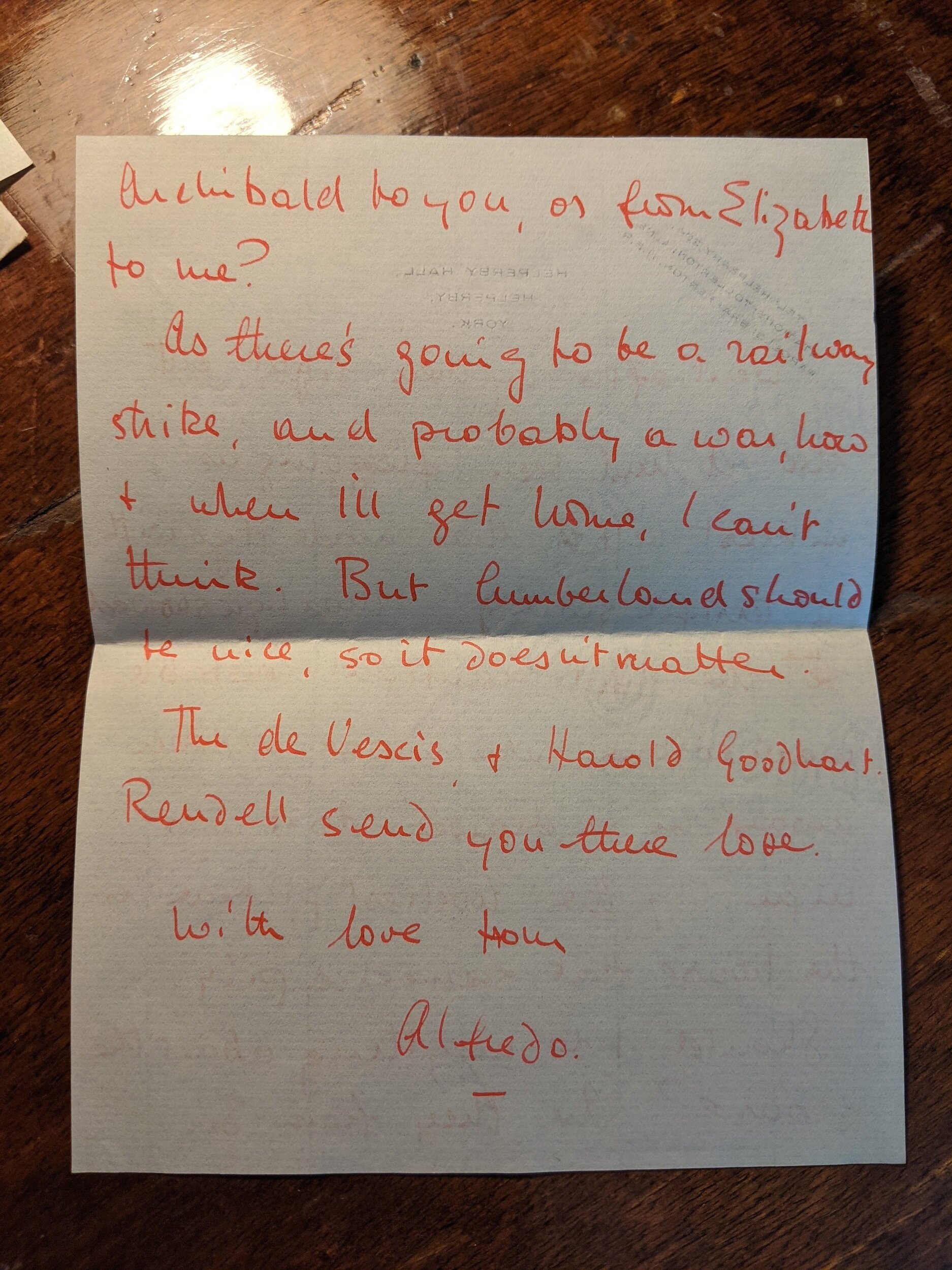

Two days later, Alfreda’s frustration with the people around her not caring about the tense state of politics boiled over, so she wrote to her mother, Gladys Huntington, saying “As there is no one here interested + as I have very definite views, I have to tell them to you, at the risk of boring you.” In her letter, Alfreda shows that she pays a great deal of attention to the world around her, referencing past events and the far-reaching implications of current events.

Dearest Mother,

If our present firm line can only prevent Hitler from attacking Poland this week, and next he might pause to take breath before trying again, as he did the first time over Czeckoslovakia[sic] the spring before last. In which ease the treaty with Russia may have been his first serious mistake - because it has frightened Japan, worried Italy, maybe hurry up our own pact with the Soviet, and perhaps even, carefully, hand [kel?], alienate his own people. ^[Without doing him any good, as it means nothing] But if he thinks, as he easily might, that by presenting England with a conquered Poland, he would once more avert war - I think he would be wrong, + we’d be at war by next week. What do you think?

The people here are taking comparatively little notice of the situation, though Auntie listens to the news, and Goodhart. Rendell (is he Mr. or Sir?) frightens us by saying that “Edward” (Lord Halifax with whom he’s been staying) thinks only a miracle can save us from war within the week, while the de Vesei’s are very worried.

Yesterday at the races we heard for the first time of the agreement, it wasn’t in our morning papers - we understood it to be far worse than it was, and [Pinkie], Martyn, + I sat thinking war would be declared today. I’ve never been so miserable. Now I think there is little hope.

As there is no one here interested + as I have very definite views, I have to tell them to you, at the risk of boring you -

How lovely to think that you’re back at last. Was it fun till the end? I do hope so -

Very best love

Alfreda

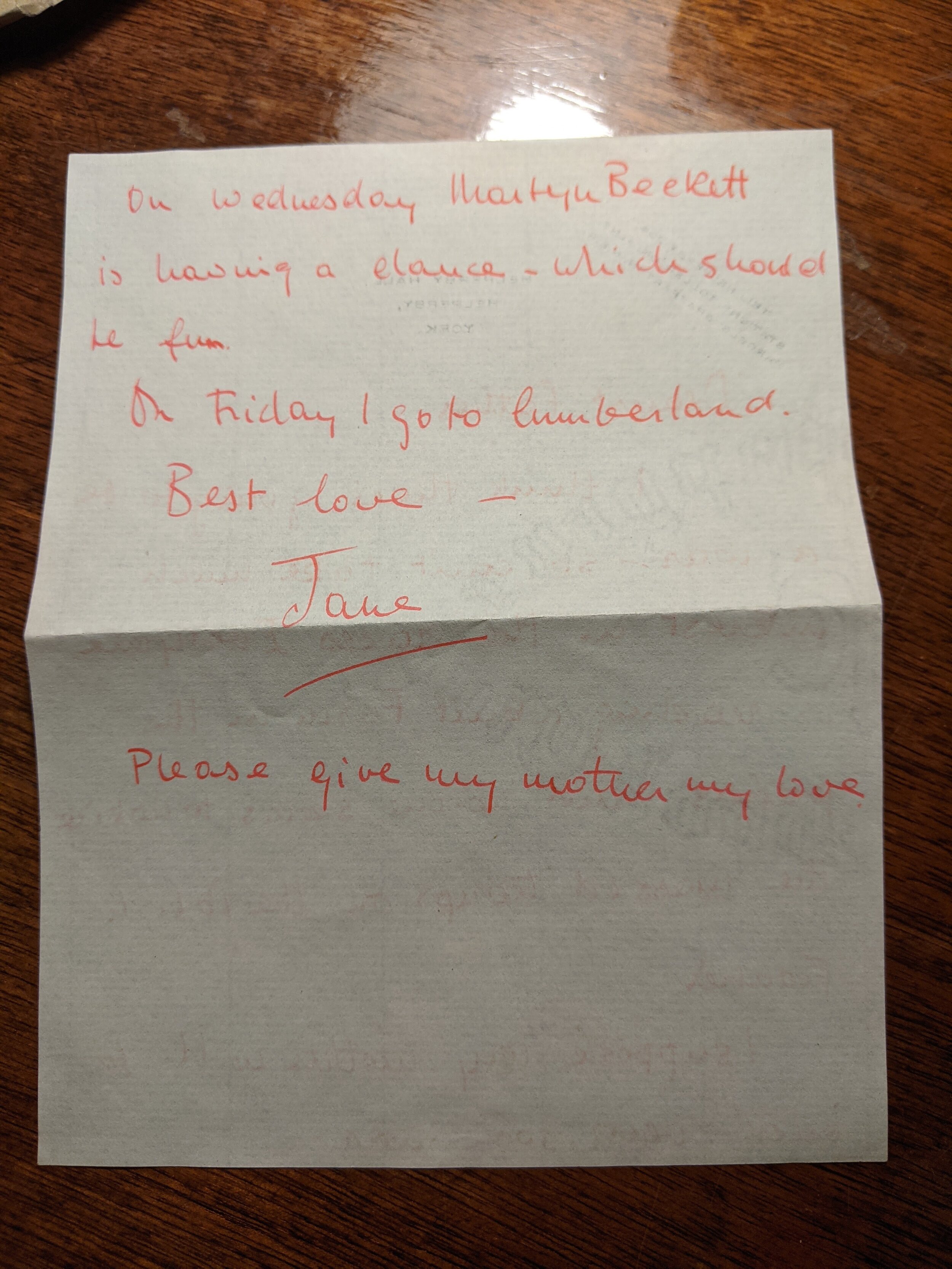

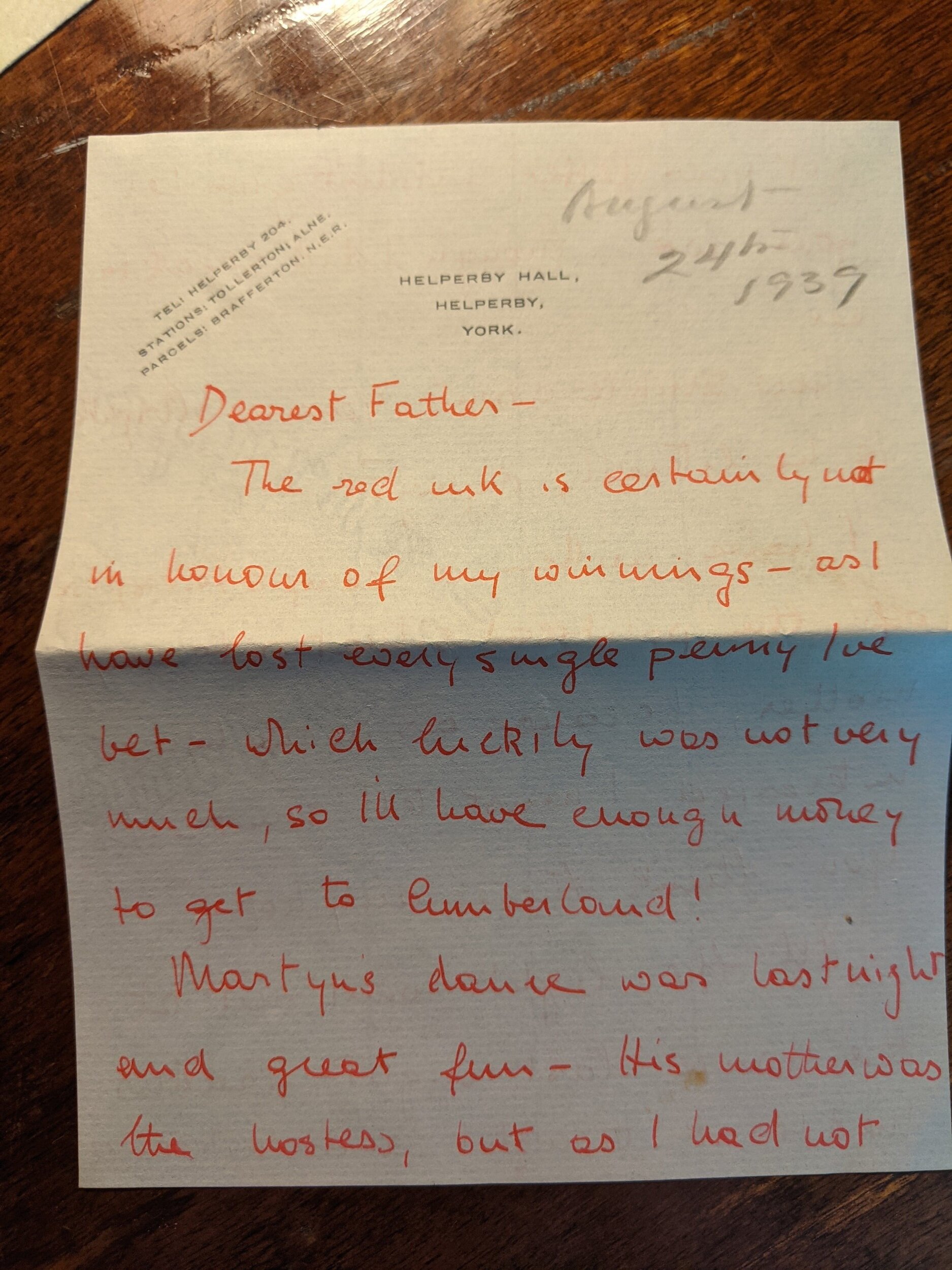

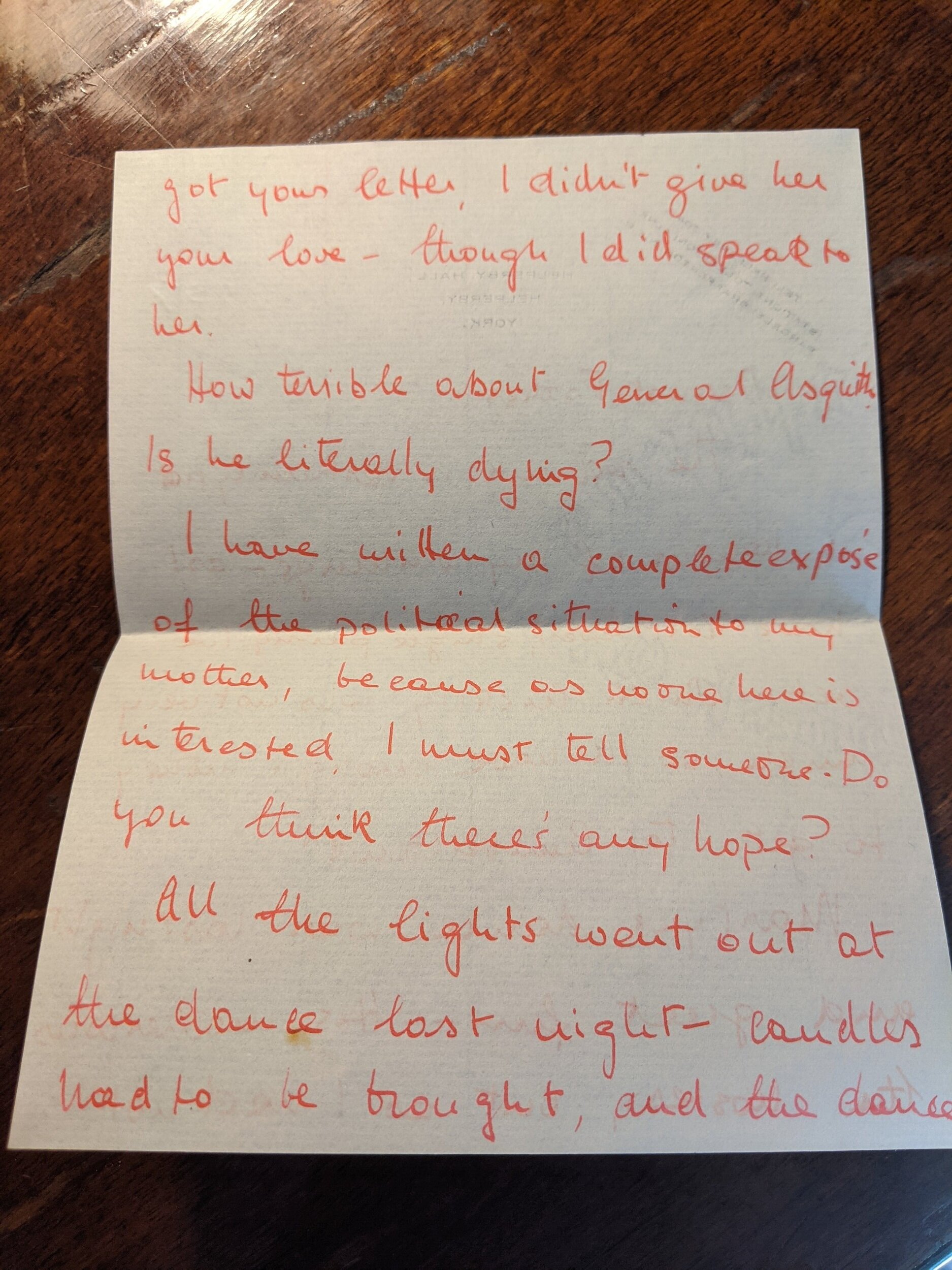

Dearest Father -

The red ink is certainly not in honor of my winnings - as I have lost every single penny I’ve bet - which luckily was not very much, so I’ll have enough money to get to Cumberland!

Martyns dance was last night and great fun - His mother was the hostess, but as I had not got your letter, I didn’t give her your love - though I did speak to her.

How terrible about General Asquith. Is he literally dying?

I have written a complete exposé of the political situation to my mother, because as no one here is interested I must tell someone. Do you think there’s any hope?

[…]

As there’s going to be a railway strike, and probably a war, how + when I’ll get home, I can’t think. But Cumberland should be nice, so it doesn’t matter.

[…]

With love from

Alfreda

One can imagine that Constant was much less cavalier about the potential for Alfreda’s being stranded from home for the foreseeable future than she was. It probably mattered quite a bit to her parents.

Leo Myers discusses only the coming war in his letter to Gladys of August 27. He expresses concern for Gladys’ going to London, but the way he goes about it strikes an outside reader as amusing or odd: “I think you would find a bombing a very disagreeable experience…”

Aug. 27th

Dear Gladys, the news looks very black this morning. - I wish Constant would settle his affairs quickly, so that you don’t have to go to London. I think you would find a bombing a very disagreeable experience - especially the waiting - while they were evacuating the children. I shall have two refugees & two invalids in this little house, a [???], I suppose, I shall retire - for the next two years. My family is all settled at Erwarton with a fire dug-out. Goodbye to civilization & all that!

Yours,

Leo

A disagreeable experience is certainly one way to put it!

A Nursery School: Watlington Park Children in Wartime by Ethel Gabain, Lithograph, 1940. IWM ART LD 263.

This letter also provides us some insight into the quotidian concerns of the English gentry—how to deal with young, restless daughters. Although better than a son who could be drafted, parents of young adult daughters also wanted to keep them out of danger while allowing them a certain level of independence.

Sept. 28, 1939

Dearest Gladys - I was so glad to have your letter - I hadn’t heard of you for such ages, except through Dorothy. How awful it all is - and will be worse of course. One dreads so those lists of casualties…

Fortunately I am + have been very busy settling all these children into the house. With the innumerable problems that arise - but with the aid of my perfect + absolutely indispensable Irish cook + the house-carpenter we are getting it wonderfully straightened out and settled down + I am getting used to the noise - it’s only the smell in the dining room that I find hard to bear!

The isolation is going to be very depressing + I shouldn’t wonder if we took a little flat in London later on. But like everyone else one is waiting for the first air-raid…. Meanwhile I have found both solace + amusement in reading. What a good book the Prince Imperial is! - do congratulate Constant from me, it should surely do well - too good for a best-seller, but the Book Society recommendation ought to do a lot for it + the intelligent reading public will love it - as I did.

[…]

The only problem that really worries me at present - and must also worry you - is what can we do with our young daughters? The bottom of their little world has dropped out - they are bored, unhappy + désoeuvrées - and yet I don’t think we can let them, at 18, go off alone to join one of these Womens’ Armies - Do you? Dorothy suggested P’s learning to type + shorthand + then she might get some voluntary office job - Quite a good idea, but of course like most war work it entails living in London, and how can we tell yet about that? Then, I am [longing?] myself to do something to help with the war - but it is different for me as I know I am being of use here. But I do find an idle restless unhappy daughter in the house a problem! What do you + Constant think we can do? If only the young weren’t so terribly secretive! Of course they tell each other everything. Perhaps we were the same.

[…]

All love, dear Gladdy

Antoinette

From Gladys Huntington’s photo album that started in 1932, we discovered that the Huntingtons also took in evacuated children. A photo from 1940 has a caption reading “Evacuated children - A picnic on first anniversary of their coming to us - Sept 2nd - The Flooded Wildbrooks.”

Alfreda still goes to the dance and the races, Constant’s business continues on uninterrupted, and Leo goes on commenting on the weather, all while facing down an impending war. To be fair, none of them could know it would become a second World War and none were of the age or gender to be drafted or asked to fight. But generally, life doesn’t stop when a country goes to war or the world changes irrevocably. Ordinary people went to work after the nuclear bombing of Hiroshima and the world hasn’t stopped for the almost 2 million people who’ve already died due to COVID-19 just in 2021 so far.

[2] Clouting, Laura. "The Evacuated Children of the Second World War." Imperial War Museums.