The Circular Quarterly Letters: The Early 20th Century as Experienced by the New England Elite

< Back to Collections

Written by Alyssa Salzberg, Museum Assistant on June 27, 2020

The Circular Quarterly was an unofficial newsletter consisting of letters between a total of twelve classmates from the Harvard graduating class of 1897. Four times a year, each contributing member would send a letter to the Editor (a role that rotated between classmates from year to year) about the recent events of their lives and of the world, and comment on the politics of the day. The Editor would then have these letters typewritten and send them back out as a full set to all members. This was a tradition started by a group of friends in 1902, meant to be a way of keeping in touch and updating one another on their lives; by the time of the newsletter’s dissolution fifty-eight years later, it had become not only a collection of immense personal value to everyone involved, but also an exhaustive and frankly-stated record of the turbulent first sixty years of the twentieth century. Through these letters, we are granted a look into past events not simply as they happened, but as they were perceived to happen by the New England elite who hovered on the periphery of political power.

One of these 1897 Harvard graduates was Henry Barrett Huntington (called ‘Barrett’ by his friends and family). He was not one of the CQs (as the letter-writers referred to one another) from the group’s inception, although he was acquainted with all of the original members from his college years; he was, instead, invited to join in 1925, at which point there were seven other contributing members. The museum’s collection of CQ letters, donated by Lisa Dyer Merrill, is his set, beginning with his first quarter in 1925 and going all the way through the group’s dissolution in 1960. The letters span an era of upheaval and uncertainty, prosperity and decline, documenting the tail end of the Roaring Twenties, the Great Depression, the splintering of the League of Nations, World War II, the Cold War, and the Korean War—to name only some of the globally significant events discussed at length by the CQs.

The CQs prided themselves on having a broad range of intellectual dispositions and opinions, but, in reality, they represented a relatively narrow perspective on the world, all of them being white, wealthy, college-educated New England men. Their political ideologies differed to a sometimes-surprising extent, all the same, with members from several different political parties and with widely varying ideas of what the world ought to look like, and these differences widened even further with age, though the classmates’ affection for one another remained steady. The position from which the CQs saw the world was notable in how it affected their opinions and outlooks, as well as how it failed to affect them. They had access to fairly delicate information on events and political figures, both domestic and abroad, that gave them a more complete look at foreign affairs and then-current events than many people were able to access at the time, and yet they watched the world with a striking distance and, occasionally, blithe disaffection afforded them because of their class, age, and status: all of them were too old to sign up to fight in World War II themselves, and wealthy enough to continue to live in relative prosperity even during the worst of the Great Depression, as well as through the heavy rationing and uncertainty of World War II. The CQs were deeply dissatisfied with the turmoil of the world they inhabited – this was a constant, for all of them – but this dissatisfaction, while leading them in a range of different ideological directions, did not result in much direct political action, if any. Their views on the world are those of (admittedly well-informed) outsiders, confident that they could weather whatever direction the world took without having to go too far out of their way. Which is to say, the CQs observed the world closely, while having the privilege of deciding when and how to participate in it directly.

This brings us to the first of many earth-shaking events that the CQs witnessed: World War I. The CQs all would have been in either forty or forty-one years old when the United States joined the war, meaning they were older than most recruits, but still perfectly eligible (though not required under the draft) to go to war—a war that was, at the time, unprecedentedly brutal. Several of the CQs signed up to fight in the war, and although our letters only go back to 1925 (seven years after the war had ended), they do very occasionally discuss their service. It comes up rarely, and usually in passing, and never in the gory detail explored by comprehensive histories of the war, but it did certainly leave its mark. One of the most notable and extensive mentions of World War I is in a letter from November 16 of 1933, written by Charles Davis Drew while he was vacationing in Europe. In this letter, he talks of the changes in the landscape since he was last there:

The morning journey from Paris to Boulogne was full of memories and the re-awaked emotions of war-time, for I had not seen the war-zone since 1918. At that time Amiens was deserted, except for a few military police to prevent looting, and the station and railroad yards were under fire from the German lines 10 miles to the eastward. In 1918, our train was routed around the west side of the city and ran dead slow between huge fresh shell-holes. At Abbeville, one third of the main street was in ruins from air-bombing. It is now entirely rebuilt. In 1918 the ridge of sand dunes behind Etaples was covered for a mile with hospitals and rest barracks, and one saw thousands of men in khaki and scores of nurses in blue and white. Now there is nothing behind the sleepy village but the high dunes, sparsely covered with gorse and stunted twisted beach pines. That is to say, nothing but the huge cemetery and war memorial, with the Union Jack flying over it. At Boulogne, on Nov. 8th, I saw thirty smacks unloading huge catches of herring. They were lying in the berths occupied in 1918 by the hospital steamers, into which I saw the endless procession of “stretcher cases” being carried from the hospital trains on the quai. The last time that I had crossed the straits, our transport was jammed with khaki-clad men, all wearing life-preservers, and we were escorted by six destroyers and two “blimps.” And I found myself speculating as to whither this strange old world has been moving since the “war to end war” came to a finish fifteen years ago.

The transformation described here is all the more evocative in hindsight, knowing that before the next fifteen years were out, France would have been occupied by invading Nazi forces and would be doing their best to rebuild yet again, from an even more destructive war.

Before the second world war, though, were a number of other tribulations – chief among them, the Great Depression, whose effects fell very differently on different CQ members. Henry Wilder Foote (referred to in the letters as Harry Foote), for example, had to constantly refigure the budget of his church – he was a Unitarian minister – as his disciples were able to donate less and less over the course of the 1930s, and he spoke frequently about scraping together the resources to do more charity work for his ailing local community. On the other end of the spectrum was James Duncan Phillips (who went by ‘Duncan’), the vice president and treasurer of the very successful Houghton Mifflin publishing company, who seemed to doubt the very existence of the Great Depression, decrying not the economy or public management of it but the supposed laziness of the people. Duncan was a firm believer in the old American ideal that every man is what he makes of himself, and that anyone could go anywhere they wanted if they simply worked hard enough for it, so he never quite accepted that the Depression was taking opportunities away from people. He wrote in a letter on May 25, 1932:

The present situation makes me very angry. In the first place I think the thing which is doing the most damage is the constant weeping and wailing which is going on and the demand for relief programs. I can see no sign of 5,000,000 unemployed. […] Recently there was a so-called unemployed demonstration on the Common and in a crowd of perhaps 1000 I failed to see more than four men whom I should call poorly dressed; all the rest had clean, neat clothes without patches in their pants, good looking hats and neckties and collars. […] Once you advertise relief for the proletariat it will turn up in ever increasing numbers. The relief I want is for Congress to balance the budget and go home and shut up. The latter is the most important.

Duncan was by far the most outspoken and vehement of all the CQs about his political beliefs – as evidenced here, where he appears utterly convinced that the greatest crises of the Depression were manufactured or nonexistent. (For the record – according to the U.S. Census Bureau, there were actually more like twelve million unemployed in 1932, not five, and the unemployment rate was about 23.5 percent.) Indeed, he was a very colorful writer, for lack of a better word, and his sharp and vitriolic attitude towards the world directly juxtaposed with the friendliness and gentle affection he had for his friends (he often lamented how infrequently he was able to meet up with the other CQs, and expressed regular, active, and unselfish concern for their wellbeing) made him perhaps the most interesting character of the whole bunch. That is to say, the most interesting of the bunch, with the possible exception of Roland Burrage Dixon, who had by far the most interesting (and likely the most prestigious) career of any CQ. Roland was a cultural anthropologist, and traveled all over the world to study culture, mythology, and linguistics, among other things, before settling down to teach as a professor at Harvard. However, Roland is only present for a very small portion of the letters held here at the museum; he died at age 59, on December 19, 1934, of cancer.

Roland’s death was one of the most personally devastating events to affect the CQs, in contrast to far more globally tragic occurrences that passed them over. The letters following his death contain a number of lovely tributes and recollections. One of these comes from Charles Drew, on March 5, 1935:

Early in our Freshman year, the luck of the alphabet brought me as my left-hand neighbor in History I a rather pale, quiet, mature-looking, studious youth with a mustache. From time to time we exchanged a few remarks about the course. One evening I went to the old room in Hastings where he lived to borrow some notes or a book in connection with the work. My History I acquaintance was out, but his room-mate came to the door and got me what I wanted. The room-mate was a dignified, shortish, clear-complexioned lad, with black hair and very blue eyes that looked straight at you. At that stage of his career he was clean-shaven. Such were my first meetings with Roland and Sinclair. […] [Roland] was always to me the cheery, tolerant, tireless, even-tempered, and unselfish companion of the woods. I shall never cease to be thankful for the two delightful days that Helen and Henry Hubbard and I spent at his house last March. He was in his most genial mood – the perfect host. That is my last and one of my happiest memories of Roland.

The ‘Sinclair’ mentioned in this letter was Sinclair Kennedy, the founder of the CQs, and a childhood friend of Roland. Roland’s passing was the catalyst for Sinclair to leave the group in all official capacity. On February 18, 1935, he wrote an eight-page letter recounting his friendship with Roland and declaring his intentions to leave the Circular Quarterly behind. He continued to receive copies of it, and he did, in the end, make a number of further contributions, but these were few and far between. In his final ‘official’ letter, he says:

When we walked about together, all over Cambridge and elsewhere, Roland was somehow always at my right hand and a bit ahead of me, no matter what my pace. I grew to take this for granted and used to joke him about his inability to walk abreast of me, but he never for long succeeded in changing his position. Later I began to think it was perhaps symbolical of our companionship. Often the last 15 years I have thought I would get ahead of him in the last accomplishment of life. But he has kept ahead of me to the end. […]

This Circular Quarterly has had a glorious career and a life longer than most of its contemporaries. […] It has been a free press for free speech!

I wish now to bring to a close my activities for and with it. At sixty years of age, I consider it time to lessen the number and the responsibilities of fixed dates. It is my hope many letters will pass between me and the present C.Q. subscribers. But I wish this to be my final contribution.

The other members of the CQs were ever-hopeful that Sinclair would start contributing regularly again, even years later, and they visited and spoke of him often, but he was never present in the letters in quite the same way again. A few years later, in 1939, they invited a new member, Henry Scott, feeling “[their] ranks [had been] somewhat depleted.”

Next on the list of major events in the lives of the CQs was the second world war. During the whole of the war, as well as the years leading up to it and during those years that the war was ongoing but the United States had yet to join, the political discourse in the group was especially lively. Many of them had children who were of the right age to fight, which heightened things still further. Charles Drew had one son on the ground and another in the air force. Harry Foote had a pacifist son, Caleb, who was imprisoned for being a conscientious objector. Jobs were also affected heavily; Henry Barrett Huntington, who taught as a professor at Brown University, spoke of the increasing complications of trying to organize classes for students planning at any moment to go to war either by choice or by draft, as well as the various programs of study for those coming back, having spent what would have been their college years fighting the Axis powers. The letters from roughly 1938 to 1945 display many sides of the American standpoint on the events of World War II and how that standpoint evolved and changed over the course of the war. Charles Drew writes at length on the start of the war in his letter of December 1st, 1939:

Three days after I had written my last contribution from a remote New Hampshire hillside, I realized that we were witnessing what in 1918 I had never expected to experience again – a Great War. And in many ways I regretted that I had lived to see such a thing.

Yet how different 1939 in the U.S. is from 1914! The other war was vastly exciting to Americans, like the biggest World Series they had ever known, and everyone “rooted” loudly for the Allies... […] Cartoons depicted the Kaiser as a madman, Germany as a brutal beast, and the British Lion as the symbol of steadfastness and indomitable resolution. Blood was thicker than water.

How different now! How cool and detached we are! We don’t even get excited over the rape of Poland and Finland. We make a lot of faces at Hitler and Stalin, but Britain and France are, after all, wicked imperialist powers, who threw away in the 20s and 30s their great opportunity to settle the problems of Central Europe by fostering democratic institutions. […]

I agree with Hoover that as the U.S.A. is now constituted we are too inept in foreign affairs to be of any use in trying to assist Europe to settle her affairs. Largely through our failure to participate in the most promising attempt ever made to establish a world order, that attempt failed. We ought to help the world to try again, but in my opinion we never will. If worst comes to worst and we have to save the British Empire to save our own skins, we shall turn over a defeated Germany to the Allies and to the fate of Carthage. […]

The whole thing is such a mess and a headache that I hate to dwell upon it. And our real stake in the 1914-1918 affair was actually insignificant compared with what it may be within a year in the present war….

One of the recurring themes of the CQ letters of 1939 and 1940 was the ongoing debate about American isolationism, also known as the ‘America First’ movement, which espoused the idea that America should avoid entering the war at all costs. By the time the United States joined the war, all of the CQs had fully come around in strong opposition to isolationism, but, as evidenced by Charles Drew’s own statements in the above letter, feelings were initially more mixed. Interestingly enough, most (if not all) of the isolationist-leaning sentiments expressed by CQs very clearly came from a lack of confidence in the States’ ability to get anything done, rather than any desire to save soldiers and resources. In a letter of May 29, 1940, Barrett states:

The outrages in Europe have thickened and darkened appallingly since March 1st until now the situation is almost too bad to think or write about. It seems a most damning indictment of the intelligence of the human race that such horrors should take place. Clearly to pit more soldiers, however brave, against these infernal machines brings about a slaughter like that of savages armed with clubs & spears before so-called civilized assailants with their shot and shell. It is ghastly to contemplate. […] As to the domestic situation, tho’ it seems horribly smug & selfish, I can’t see that our armed participation is called for. I almost wish it were. Certainly the danger of our being drawn in becomes increasingly threatening. I should like to see us aid the Allies with money and materials, but I am not sure that even that is promising and wise. America is so far from being internationally minded and by that I mean able & willing to take a part in world-politics. We certainly flubbed matters badly in 1918 and after….

The mistrust for how the United States government would handle the war was shared by many of the CQs, but this feeling was eventually superseded by the obvious need that the Allied forces had for more troops. Some of the CQs predicted this need well in advance, like Henry Scott, who said in his letter of May 31, 1940:

Events move so fast in Europe and Congress is so uncertain and so clumsy it may be too late. And then what? God only knows what misery is in store for the world. We should prepare for the deluge. Soon or late can we escape being engulfed in the war? For the sake of all we hold dear, for decency, honor, civilization itself, for Christianity, and our own future safety we should aid the British and French before it is too late.

The war would come to affect many aspects of life for all Americans, including the CQs, and after the United States joined the war in 1941, references to rationing and other domestic hardships became ever more frequent. Then, of course, were the trials and tribulations that came with having children fighting in the war. This was an area in which the CQs were all quite gung-ho, with Harry Foote remarking at one point that he “only wished we had more boys to send over.” However, there were distinct moments of anxiety. One of the most dramatic personal stories from the CQs over the course of WWII was an account of Charles Drew’s oldest son, Allen, being shot down from his plane over France. There was a long period of time when Allen was missing in action, and although Charles was very sure in his letters that Allen would be all right, it was by no means guaranteed. In the end, it turned out that Allen had gone underground for a few weeks, sheltered by an elderly French man living in the countryside in quiet opposition to the Nazis, and was later taken as a prisoner of war while trying to get out of France. (He was all right, in the end.)

With the end of World War II came the requisite discussion of the atomic bomb, about which there were mixed feelings. The end of the war was a great relief to everyone, naturally, but came with a whole host of complications: there were the moral quandaries of the atomic bomb; the postwar attempts of war-ravaged countries to rebuild, with varying degrees of success; the questions of what to do with Germany; how to form a sort of international government that would not fail like the League of Nations had; and the political situation of Russia. Barrett Huntington commented on the brutality of the atomic bomb in his letter of August 29, 1945, two weeks after Truman’s announcement of the unconditional surrender of Imperial Japan:

I can’t unqualifiedly approve our use of the atomic bomb and its horrors. […] It is clear that a force has been unleashed–and it can’t be kept secret long–that may easily bring an end to our civilization. Indeed, it is arguable that scientific discoveries are so far ahead of our social and moral control of their use that in a few generations we shall utterly destroy ourselves. An automatic pistol in an unsupervised nursery school may be the symbol of our future!

Grim as that particular bit of imagery is, the future was looking a bit brighter with the war finally over. However, a wave of personal tragedies hit the CQs over the next couple of years: James E. Gregg, who had joined the CQs in the same year as Barrett Huntington, died in February of 1946; Sinclair Kennedy, the erstwhile leader and still close friend of the CQs, died in July of 1947; and Henry Hubbard, a steady presence amongst the CQs from the start, died in October of 1947. By this point, everyone in the group was around seventy or seventy-one years old, and the reactions to these deaths are a bit quieter and more subdued than they were for Roland’s death ten years earlier, although the sentiments expressed are equally heartfelt.

The following five years or so of the CQs consist largely of discussion of the members’ personal lives and political opinions regarding McCarthyism and the Cold War. Even the most anti-communist of the CQs (Duncan) harbored a severe dislike for McCarthy and his particular methods, and Harry Foote went so far as to call him “that scurrilous super-skunk of the Senate.” Needless to say, discourse in the group remained colorful. However, the group continued to lose members, as Henry Scott died in May, 1952, and then Duncan in October of 1954. Thus, by 1955, there were only three CQs remaining, each still dutifully writing their quarterly letters: Barrett Huntington, Harry Foote, and Charles Drew. The death of Duncan, in particular, who had such a large and loud presence in the letters, left quite a gap behind him, and although the Circular Quarterly would continue for another five years, it lost much of its spirit with him. The CQs had been speaking for years, by this point, about donating their sets of letters to Harvard libraries or local historical archives, and the conversation was revivified as the CQs seemed to be coming to a close. Harry Foote looked back on the long history of the CQs in his letter of February 22, 1955:

Dear Seekews, –

Of late, in the endless process of “clearing up,” I have gone through my file of C.Q. letters from the first issue in December, 1902, to date, preparing eventually to deposit them in the archives of the Class of 1897 at Widener Library. I don’t mean that I’ve read through the entire set, which I figure would require an uninterrupted two months, but I’ve caught a bird’s-eye view of the long half-century; and many a forgotten incident has come to life again.

If I do say it, I think they set forth a very interesting and creditable record of thought and activity, in widely differing fields and with a marked variety of vigorously held opinions. Four of us – Roland, Sinclair, Charles, and Duncan – were world-wide travellers. None of us have attained any great distinction, but each has made his contribution to the common welfare and has left an honorable name. The net effect on me has been one of deep gratitude for fellowship in our little brotherhood, and the emotion which Tennyson expressed, better than any one else, in his poem, “In the Valley of Cauteretz,”

‘All along the valley, stream that flashest white,

Deepening thy voice with the deepening of the night,

All along the valley, where thy waters flow,

I walked with one I loved two and thirty years ago.

All along the valley, while I walked today,

The two and thirty years were a mist that rolls away;

For all along the valley, down thy rocky bed,

Thy living voice to me was as the voice of the dead,

And all along the valley, by rock and cave and tree,

The voice of the dead was a living voice to me.’

Now only three of the twelve of us are left to date our letters in 1955, but while life lasts let us hold together in this bond of precious memories.

The Circular Quarterly was, from its conception, just a group of friends keeping up with each other’s lives, but the end result of their correspondences was a broadly informative, religiously-kept, and deeply personal record of over half a century. The very last letter, by Charles Drew, was written on March 16, 1960, and officially brings the Circular Quarterly to an end. It closes:

As our C.Q. dates – March, June, September, and December – roll around, let us give a thought to our dear associates, living and dead; and remember that a few lines of cheer in a letter may mean a lot to both sender and recipient.

Ave atque vale

Affectionately,

(s) Charles D. Drew

Editor pro tem.

F I N I S

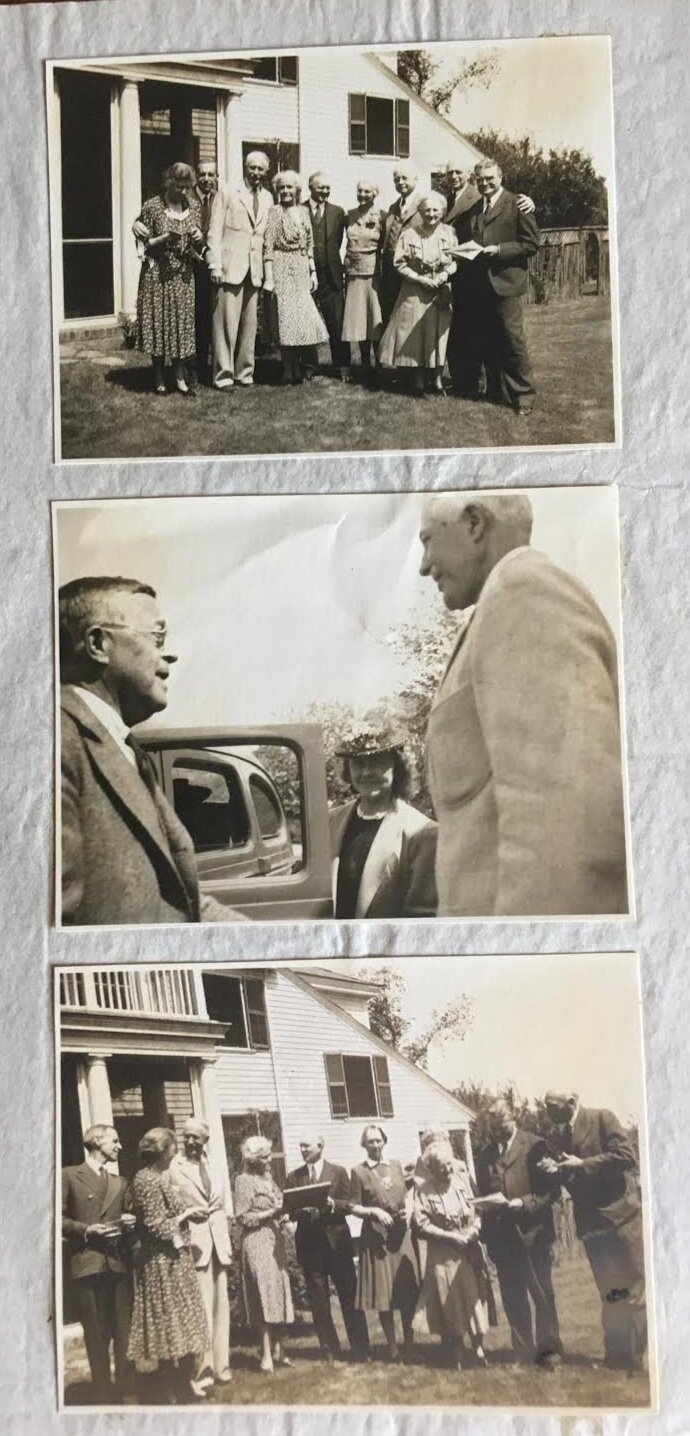

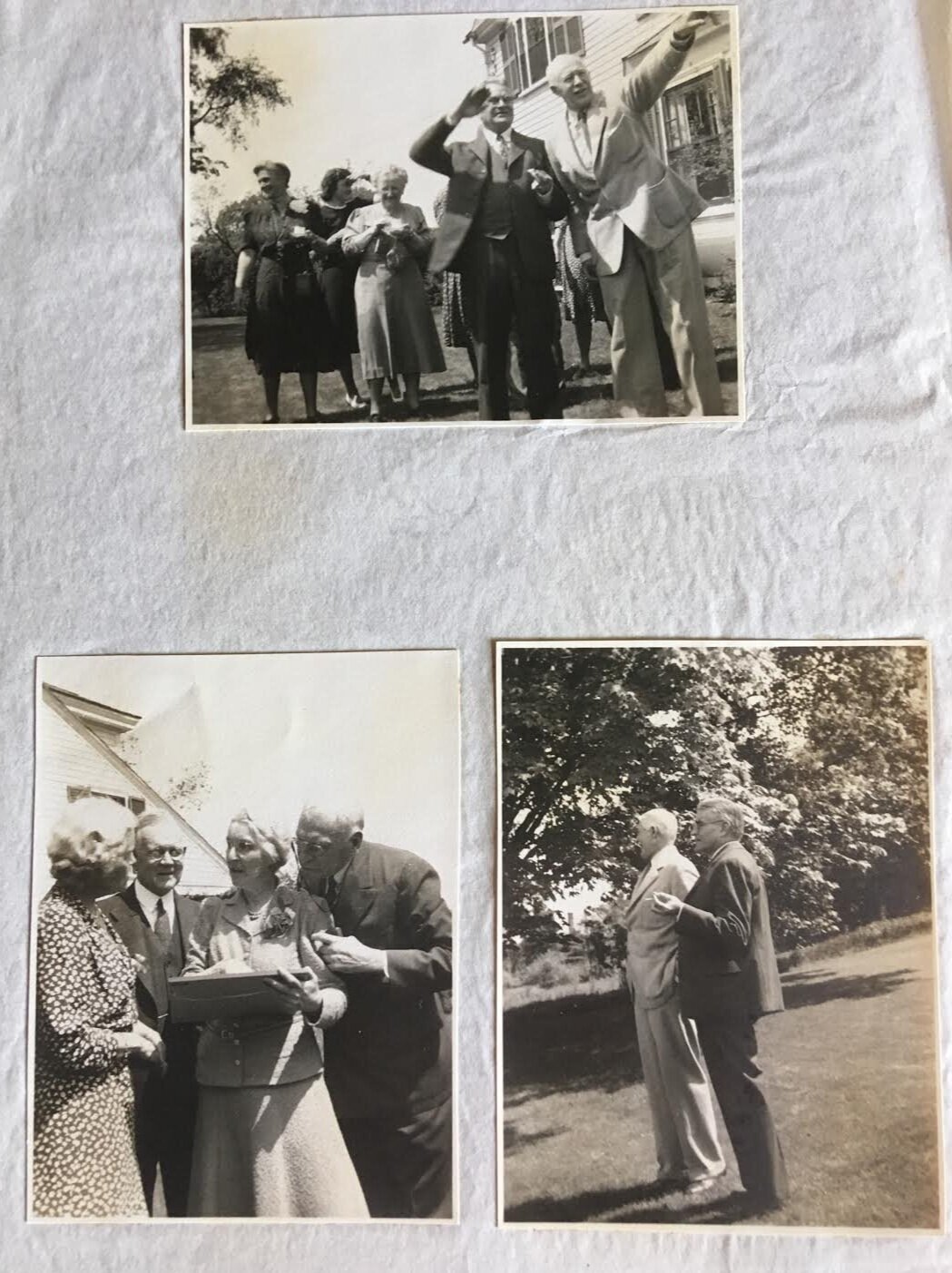

Circular Quarterly Reunion, May 30-31, 1940. Includes all CQs and their wives, excepting Alice Huntington, who was ill, and Sinclair and Rachel Kennedy. Harry Foote’s daughter Agnes also attended.