Indigenous Land Stewardship: Past and Present

Lovell, John L., 1825-1903, “Mount Sugarloaf in South Deerfield,” Digital Amherst

For over 11,000 years, Indigenous peoples have maintained a vast and complex relationship to this region’s natural environment. The lives of the earliest Indigenous inhabitants were defined by the contours of an ancient 350-mile glacial lake that covered much of the present-day Connecticut River Valley between 15,500 and 11,500 BC. Algonkian oral historical traditions and Indigenous “deep-time stories” about the distant past reveal how Indigenous peoples in this region witnessed the formation of this glacial lake through a series of sediment dams. These oral traditions tell of a “Great Beaver” that dammed and flooded the Connecticut River Valley, only for Obbamakwa, a powerful earth-shaper, to break the neck of the beaver and allow the glacial lake to drain and the Connecticut River to flow through the valley. The body of this beaver forms what is today known as Mount Sugarloaf in South Deerfield.

Earth-shapers like Obabamakwa dramatically manipulated the landscape, but so too did centuries of Algonkian intervention and land management practices. As Abenaki scholar Marge Bruchac notes, when Anglo-European settlers arrived in what is today western Massachusetts, the “valley bore obvious traces of sophisticated human modifications, including numerous well-trod and well-marked trails that eased travel through this supposed wilderness.” These well-marked and well-trod trails interweaved throughout a carefully managed landscape of forests, open fields, and agricultural lands. Algonkian-speaking residents of the Connecticut River Valley practiced forest management techniques that included controlled burnings and the clearing of land and brush for agricultural purposes. The ecological effects of these controlled fires were numerous: controlled blazes increased the rate at which forest nutrients were recycled into the soil, thus making it richer, and created distinct boundary zones that aided in the hunting of wildlife. By 5,000 BC, archaeological evidence indicates that these forest management techniques were accompanied by seasonal and migrational agricultural practices that included the harvesting and storing of acorns, hickory nuts, beechnuts, and chestnuts. These starchy seeds could then be boiled into porridge in order to make them more digestible and edible.

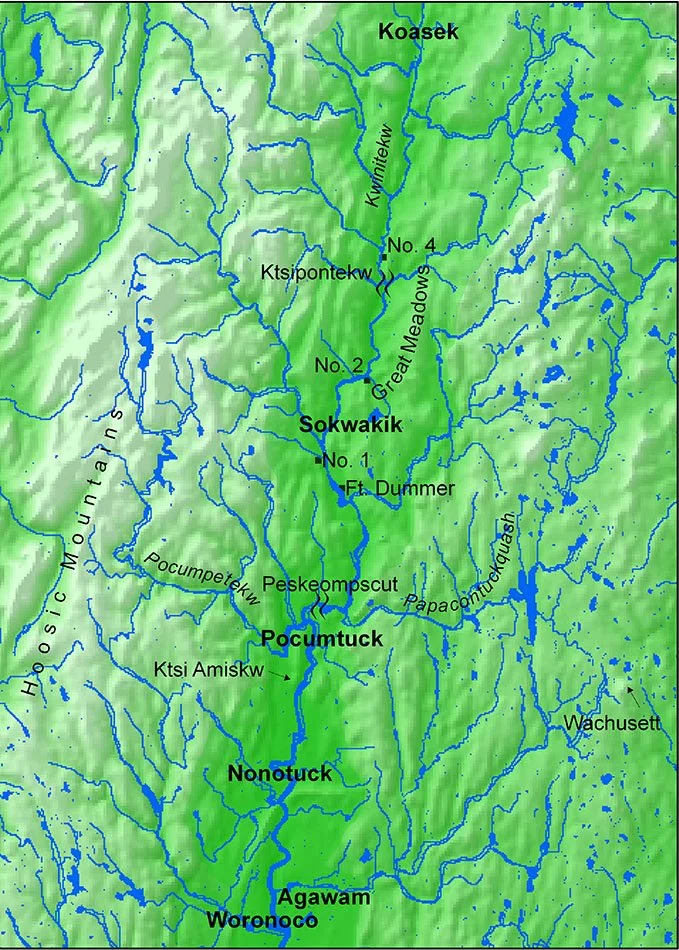

Map of the Kwinitekw (present-day Connecticut River) showing Indigenous homelands. Nonotuck indicates the rough position of present-day Northampton and Hadley. Source: Lisa Brooks, The Common Pot: the Recovery of Native Space in the Northeast (University of Minnesota Press 2008).

By roughly 1,000-1,500 AD, the Indigenous population density of along the Connecticut River—known to Indigenous peoples as the Quinneticook or Kwinitekw (“long river”)—increased alongside the intentional cultivation of corn and maize, beans, and squash supplemented by nuts, seeds, berries, small mammals, fish, and shellfish. Because maize and corn were insufficient protein sources on their own, these Indigenous residents acted as “mobile farmers” and supported this diet with seasonal hunting and gathering. By the 1500s, this patchwork of cultivated fields, cleared forests and pastures, and networks of trails was the established homelands of the Nolwottog (sometimes expressed as Norwottock and Nonotuck) who moved seasonally around their territory. The Nonotuck or Nolwotoggs as well as the Pocumtuck, Woronoco, Agawam, and other Indigenous peoples of the middle Connecticut River Valley, first encountered Dutch and English settlers about 1614 who initiated a gradual process of displacement and dispossession of the lands these Algonkian residents stewarded for thousands of years. English strategies for Indigenous dispossession were rooted in asymmetrical trading relationships: as Indigenous people became indebted to English traders, and were increasingly unable to meet their obligations with a depleted supply of pelts, English creditors gradually compelled Nolwottog leaders to yield land to settle debts. Samuel Porter (the ancestor of Moses Porter, who would eventually build Forty Acres in 1752) , working with trader John Pynchon, invested £100 in a deed signed by Umpanchela, Quanquan, and Chickwallop on behalf of local Indigenous communities that allowed the English to settle “on the East side of Quonicticot River” and stipulated clear hunting and fishing rights for the Nonotuck and Nolwottog people. In this way, the deed these leaders signed directly recognized these existing Indigenous land use and stewardship practices. But patterns of credit, debt, and forfeit in the 1660s meant that Umpanchela, Quanquan, and Chickwallop and their communities faced legal eviction from this land. By 1660, trader John Pynchon had driven Umpanchela into such debt that Umpanchela was forced to yield this ground altogether to the Hadley settlers, including Samuel Porter, who had invested in this enterprise.

This basket, one of many in the museum’s collections, could have possibly been made or sold by local Indigenous women in the Connecticut River Valley. Photograph courtesy of Brian Whetstone.

War, conflict, and legal dispossession led to further displacement in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. As Marge Bruchac notes, conflicts like King Philip’s War (1675-1676) left many Indigenous peoples in New England as refugees who sought new homes further north in Vermont and Canada or west in New York in refugee communities like Schaghticoke roughly 20 miles northeast of present-day Albany. Out of these conflicts, English settlers interpreted Indigenous presence on the landscape as hostile, leading to increased violence that encouraged many more Indigenous peoples to leave. Over time, Schaghticoke received nearly 2,000 former Indigenous residents of the Connecticut River Valley. Bruchac observes that “the absorption of Valley Natives into other Native populations was not a mysterious diaspora to a foreign country; people simply followed familiar paths to live among their cousins and allies.” But Indigenous people did not simply vanish from the Connecticut River Valley: they persisted and survived under the increased pressures of Anglo-European settlement. Throughout the nineteenth century, displaced Indigenous residents of this region and their descendants regularly returned to their traditional homelands, and those that remained adopted other strategies, like sedentary agriculture, to survive. Still others chose to circulate through their traditional homelands and kinship networks, often marketing their crafts, working as day laborers, or distributing Indigenous medicine to their white neighbors. At Forty Acres, one of these Indigenous women was Assinah, who Elizabeth Porter Phelps hired to assist with cheese production in 1803. Assinah also assisted with cleaning the large house at Forty Acres and potentially utilizing Indigenous basketry skills to make baskets for straining cheese. Other Indigenous women like Assinah wove seats for chairs, made brooms, or were hired out as farm laborers throughout Hadley and surrounding communities in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Objects like baskets in the museum’s present collection attest to the persistence of Indigenous peoples in this region and their knowledge of land stewardship and natural resources to make and sell objects that aided in their survival.