A Book Talk and Conversation with Carl I Hammer

“As an Heathen Man and a Publican” The Ordeal of Betsey Huntington at Forty Acres

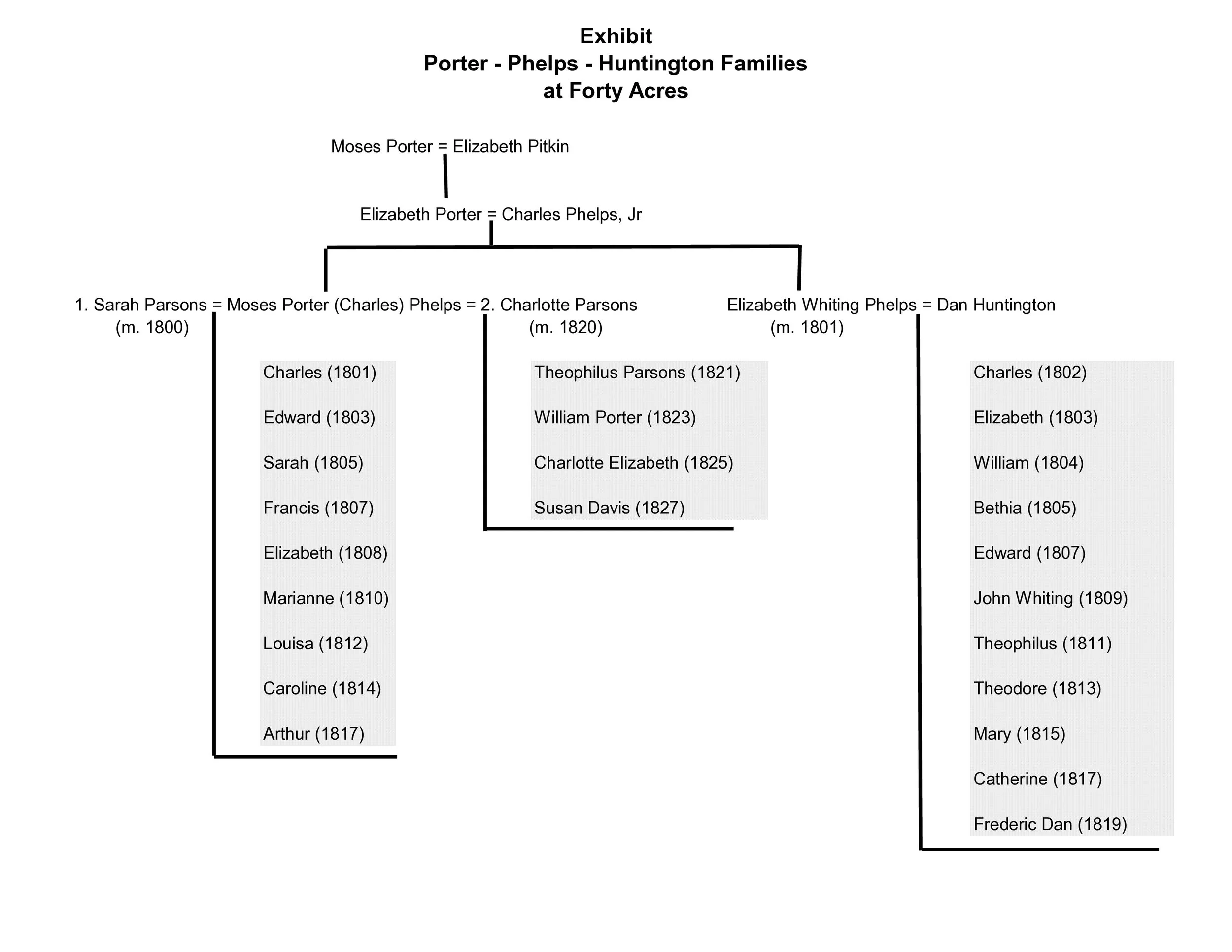

When Dan Huntington left Middletown in 1816, he was still an orthodox trinitarian Congregationalist. During his tenure there he may have been tolerant of Unitarians, but the arrival at Hadley of Charles Porter Phelps with his family in 1817 probably promoted Dan’s reevaluation of his theological views. Porter was a convinced Unitarian and had been a member of the New South Church in Boston under the charismatic pastorate of John Thornton Kirkland. Betsey Huntington too may have been similarly influenced, particularly after the of Porter’s second wife, Charlotte, in 1820. The recently discovered Phelps papers from the neighboring Phelps farmhouse – now being processed by SCUA at UMass – will hopefully provide fuller and richer insights into relations between these two large families.

Dan’s first clearly documented break with the orthodox Congregational establishment occurred in 1819. Betsey had returned as a member to the Hadley Church where she had made her profession at age nineteen. Dan had not joined the church but had affiliated with the local orthodox ministerial association. The Unitarian minister of Deerfield, Samuel Willard recalled “that Rev. Dan Huntington, who afterwards joined the Northampton Association, and exchanged labors with me in 1819, was called to an account for a violation of one of their standing rules.” Willard’s ordination in 1807 had been rejected by the Association, and he had been subject to exclusion by its members although he subsequently took particular care not to provoke and to maintain civil relations. Dan’s own later account of this encounter manifested a less irenic spirit:

“While Preceptor of Hopkins Academy, I seldom attended Associations. When I went to attend the one to which I belonged, to request a dismission, I found our moderator at his post, wide awake. He had not wholly forgotten the strays of his flock. As I went in, I found the Association had Brother [Winthrop] Bailey of Pelham, under the same condemnation of heresy on trial. The first thing I had to do was to request them to suspend operations just long enough to put me on trial with him, and as time was always precious, that it might be done forthwith. My advice was not taken. In due time, however, I was informed that a committee was appointed to look into the matter. The result, which is on my manuscripts, is not worth transcribing. My correspondence with the committee thus concludes: “I shall always be happy to see and to entertain you at my house, and if you and your worthy colleagues think proper to execute your commission, you will commonly find me near home, during the week, and may depend on a civil reception; though you cannot believe me so destitute of self-respect as to make an appointment with you that will make me in any sense accessory to the views of the Association, in the system of persecution on which they have entered, or amenable to their jurisdiction for my opinions.”

Like Willard, Dan denied the authority of the Association to regulate its members and thus the legitimacy of the proceedings. But the tone of his reply was stronger than the occasional “irony” which Samuel Willard had later regretted in his correspondence. Joseph Lyman of Hatfield, the “Pope” of Hampshire County and a family friend who had preached at Dan’s 1809 installation at Middletown, and John Woodbridge of Hadley were both prominent members of the Association, and one of them may even have been the wide-awake moderator. If they felt themselves purposely – and gratuitously – antagonized by Dan’s behavior, it would not be surprising, but Dan’s complete financial and ecclesiastical independence made it difficult to call him to account.

In late 1821 Betsey, a member of the Hadley church and, thus, under its “watch and care”, was caught up in a novel church procedure. In November a committee of the church began to visit members “to enquire into their views and feelings with regard to religion”. This and subsequent developments were recounted seven years later in 1828 in a lengthy retrospective “communication made by Elizabeth W. Huntington, the wife of Dan Huntington, to the Church in Hadley”. George Hibbard, a member of the committee, then “learned that she did not believe in the doctrine of the Trinity.” When the visit ended, Hibbard declared that they could not close with a prayer as was the usual practice “as there could be no communion when there was such a difference in sentiment.” Shortly thereafter, Dan requested a meeting of “ten or twelve of the elder brethren of the church” including deacons Samuel Porter and Moses Porter at the house of deacon Seth Smith. His purpose was to “ascertain whether Mr Hibbard expressed the minds of the church” to the effect that “there could be no communion between Trinitarians and Unitarians.” At the meeting, the assembled elders “were unanimous in asserting that their feelings were quite the opposite of Mr Hibbard’s and they would wish Mrs Huntington to attend their communion as formerly.” As a result, “encouraged by the sentiments which were then expressed”, Dan Huntington together with Porter and Charlotte Phelps, none of whom was a member of Hadley church, “soon after adopted a letter to the church through their [the church’s] Pastor requesting occasional communion”. This was refused, and “finding by this that they [the church] could not extend their fellowship to Unitarians”, Betsey concluded that “her presence at the Lord’s table was not desired, and she was exposed on communion seasons to observations which were extremely trying to her feelings.”

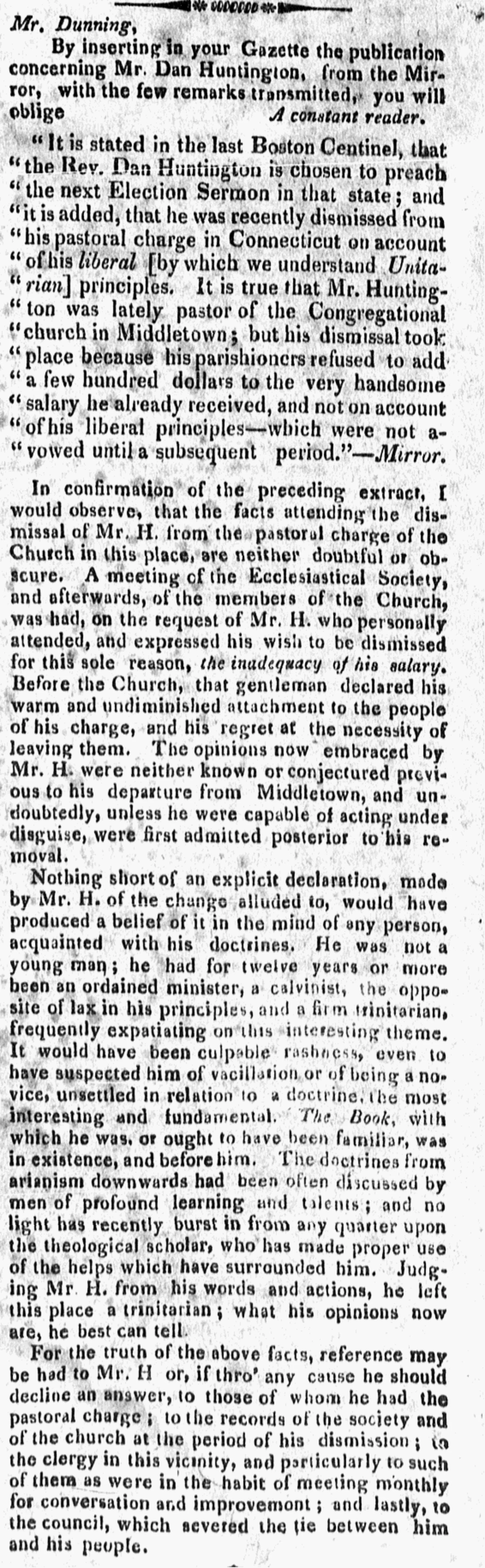

Dan’s response to this rejection by the church and by his wife’s natural reluctance to press the matter, led to a spectacular public demonstration of defiance. It was the venerable custom in the Bay State that at the annual state election in the spring, a clergyman would be charged with delivering the Election Sermon to the Governor, Lt. Governor, Council and both Houses of the Great and General Court. By custom, the sermon would then be printed at the expense of the Commonwealth. In the legislative years 1821/22 and 1822/23 Samuel Porter of Hadley, who had encouraged Dan and the Phelps to apply for “occasional communion”, sat on the Governor’s Council, and Charles Porter Phelps, who had been turned away with his wife and brother-in law, was the Deputy from Hadley in the Lower House which chose Dan on 5 February 1822.

The House’s choice of Dan was quickly noted and elicited sectarian press comment in Connecticut as well as Massachusetts. Nor did Dan’s sermon on 29 May 1822 shy from controversy; the subject was “An intolerant Spirit hostile to the interests of Society”. Dan was a skillful preacher, and he chose as his text, Paul’s encounter at Corinth with the Roman Senator and brother of Seneca, Gallio, the Roman Proconsul of Achaia. Jewish leaders there had brought charges against Paul which were dismissed summarily by Gallio: “If it were a matter of wrong, or wicked lewdness, O ye Jews! Reason would that I should bear with you: But if it be a question of words and names and of your law, look ye to it, for I will be no judge of such matters (Acts 18:14-15; KJV). The text, of course, was that the secular power should not be invoked to enforce matters of conscience, but the subtext was clearly a rebuke to all efforts to limit the freedom of individual thought and belief. This would have been clear to the audience who were accustomed to separate the implied particular from the stated general. It was also increasingly the motto of Unitarianism.

But to make the point more explicitly, Dan proceeded to rebuke the “disposition among men to control the opinions of their fellow men; especially their religious opinions” and “to consider the means which have been used by those who have undertaken thus to control the opinions of others.” Dan then proceeded to ask rhetorically, “Does the subject then admit of an application to our own community?” to which he answered:

“Let the intelligent look at what is passing in many of our Congregations and Churches; in Ecclesiastical Associations and Councils, and answer for themselves. Let them listen to the voice of clamor and contumely, of terror and exclusion, issuing from the pulpit and the press, and echoing from one extremity of our limits to another, impeaching the purest motives, maligning the fairest characters, and enkindling unjust suspicions among the uninformed.”

There is an unmistakable tone of personal indignation here over the “terror and exclusion” issuing from “Congregations and Churches, Ecclesiastical Associations and Councils” and directed against Dan, his wife and his in-laws.

Immediately after this public shaming, in June or July 1822 Dan and Betsey nevertheless visited Pastor Woodbridge at his home “and requested a dismission from the church” for Betsey. Woodbridge refused, saying that “believing as she then did, he could not recommend her to an orthodox church, neither would he to Unitarians”. When pressed by Dan for a way “in which the [church] connexion could be dissolved, Mr Woodbridge answered, “only by excommunication”. Dan replied “that he and his wife would prefer that measure to having the business remain in the present state.” Woodbridge told them, however, that he had other business to attend to first. On leaving, Dan then “added… that he should esteem it a favor to have it attended to without delay, the sooner the better.” Perhaps John Woodbridge then wondered why he should do Dan a favor.

Shortly thereafter Dan and Betsey called on deacon Seth Smith who had hosted the earlier meeting which had encouraged them to seek communion. They asked Smith and his wife about “the propriety of Mrs. Huntington’s attending the communion, and requested their advice on the subject.” The Smiths, however, declined. This was the last attempt by the Huntingtons to resolve the issue and “from that time to the present [August 1828], Mrs Huntington has withdrawn herself [excepting once when the Reverend Mr [Sereno] Dwight [Boston] administered the sacrament and gave a Christian invitation, she and her husband both stayed and partook of the ordinance”]. For Betsey, a devout member and regular worshipper, prolonged separation from the communion table must have been a source of considerable distress.

Betsey’s “communication” of 1828 then pauses with the assertion that “There is great reason to believe, that during the period of six years, the request made by Mrs Huntington [for dismission or excommunication] has never been laid before the church.” Dan’s pulpit blast against intolerance had possibly caused some reluctance within the Hadley Church to press the matter. Early in 1827, however, when orthodoxy, energized by newly-chartered Amherst College, was resurgent in western Massachusetts, the issue of Betsey’s relationship to the church, which she continued to attend was revived. In the early winter Deacon Jacob Smith visited her and “informed her that the object was to take the first step in church discipline.” When asked for the grounds, he said that it was her “withdrawing from communion”. At that point she rehearsed the earlier history of this matter and her request for a dismission. Deacon Smith then left but told her that “he should probably make another visit soon” and bring another member according to the church direction provided in the eighteenth chapter of Matthew’s Gospel.

This second visit did not occur for eighteen months until Saturday, 9 August 1828 when Deacon Smith arrived with Deacon Hopkins. They “observed [that] there was something wrong which ought to be settled”, and a discussion followed in which they were unable “to convince Mrs Huntington that she was in error having embraced Unitarian doctrines or in having withdrawn herself from the communion table.” Clearly, now the gravamen against her had been enlarged to include her religious beliefs as well as her religious practices. It is notable that Dan’s presence is not mentioned in this exchange where Betsey evidently held her own against the two deacons. He later recalled that he had been present at only one of the meetings with the deacons.

On the following Monday, 11 August, Pastor Woodbridge sent Betsy a letter requesting her “to meet with the church on the next day to answer the complaint laid against me”. On the following Sunday she noted in her diary, “The inference which I drew from this was that I ought not to disturb his feelings – nor those of his charge by attending [communion], tho’ I did attend his church meeting, and today [17 August] he has been laboring with his Church to persuade them to the duty of excommunication and church discipline – the Lord direct them in the way of duty.” Although that earlier meeting on Tuesday, August 12th did not occur, in her diary on Sunday, 24 August, Betsey noted, that “last week [she] received a citation to attend a church meeting on Tuesday next [26 August] to answer the charges brought against me – which are belief of Unitarian doctrines, and withdrawing from the communion”. This left her and Dan very little time to prepare her narrative “communication”.

The church meeting on Tuesday, 26 August did convene as scheduled. Dan apparently set the same defiant tone as earlier with the Association:

“At the commencement, we took care to let our self-constituted judges know how little respect we had for their adjudications, and that we had not come there because we were “cited” at a certain time, but, knowing them to be together, we wished to see them on our own concerns upon the business there referred to. It was not business we did not expect or which we very much dreaded.”

This last point is clear from Betsey’s “communication” submitted to the meeting which included not only the narrative of the “principal facts relating to this subject” addressing the charge of “withdrawing from the communion” but also – to the other charge – a statement of “Mrs Huntington’s belief of Unitarian doctrines” which she in no way denied. In her affirmation, regarding the key theological issue, “she does not hesitate to say that, after long and prayerful examination of the scriptures and other writings, she has become convinced that the doctrine of the Trinity, as commonly received, is not a doctrine of the Bible.”

Like her husband, she too could be a bit abrasive in asserting “as she has endeavored to follow the dictates of her own conscience and of the word of God, they will hardly expect her to acknowledge herself guilty with respect to the charges brought against her without more powerful arguments than have hitherto been presented.” Indeed, she was even a bit cheeky, noting mischievously that “she rejoices to believe that many who judge their brethren and who set at nought their brethren will be admitted to those mansions which are prepared in her heavenly Father’s house”. Nevertheless, she hoped that there will also be a place “for some whose names have been cast out as evil and who have been esteemed as the filth of the world and the disgrace of the church.” Anyone who had read or heard Dan’s election sermon of 1822 might recall his references to numerous historical persecutions against alleged heresy. Yet, Betsey remained optimistic “anticipating the universal diffusion of light and love through the world” when “mankind will one day live together as brethren”. At that time – in a short credal statement, clearly also intended as her personal confession – “‘every knee will bow to Jesus Christ, and every tongue confess him Lord, to the glory of God the Father’ – and all hearts will unite in believing that ‘there is one God, even the Father, and one Mediator between God and men, the Man, Christ Jesus.” This was a very bold confession, indeed. It is not certain that every Unitarian would acknowledge “the Man, Christ Jesus”, since the clear emphasis on his humanity – even in capital letters – tended, in contemporary terminology, towards a “Socinian” rather than an “Arian” Christology and denied any participation in the Godhead. In any event, she had knowingly provided ample evidence for the first charge of Unitarian belief.

At the church meeting on August 26th, Dan “requested in her name that she might be dismissed with a certificate of which he presented a form”. But, because “it was manifest to the church that, as her errors were of several years’ standing and seemed to be deeply fixed, and, as, moreover, all efforts for her conviction [correction] had hitherto proved wholly unavailing, it was their immediate duty to guard their own purity by some public act expressing their disapprobation of such dangerous sentiments as hers and their tender regard to the honor of their divine Redeemer”, they unanimously voted against her on three counts, thereby: [1] refusing to grant her the requested certificate of dismission, [2] withdrawing her from the church’s watch and fellowship, and [3] authorizing a public act of withdrawment “expressed by the pastor in a written form previously adopted by the church”. To this, the record of the meeting attached a copy of the “act of withdrawment” which was to be read in church on Sunday, 7 September:

“Whereas Elizabeth W. Huntington, by [her resting?] in a denial of the great doctrines of the Trinity and the supreme Deity of our adorable Saviour, and by withdrawing herself from our communion, has gone out from us because she was not of us, we therefore, declare her communion with us as a sister in the church to be at an end, and withdraw from her our watch and fellowship till such time as she, renouncing her errors, shall return to us by repentance. The above is a true copy of the act of withdrawment adopted by the church. Attest’ John Woodbridge, Pastor”

But the sting of the church’s act may have been even sharper. Betsey was undoubtably familiar with the eighteenth chapter of Matthew which established the procedure for correcting a “brother” or member of the church, first in private and then in the presence of one or two witnesses (vv. 15-16). If the brother refuses correction by them – just as Betsey dismissed the deacons – the gospel then continues (v. 17): “And, if he neglect to hear them, tell it unto the church, but if he neglect to hear the church, let him be unto thee as an heathen man and a publican.” These are very harsh terms of social as well as religious exclusion. Although we may doubt that they were observed strictly in Hadley, the humiliation for a person as pious as Betsey and also still hoping to communicate regularly must have been considerable.

In the event, we know that Betsey moved promptly to resolve her church membership. Through the autumn she did continue to attend church in Hadley and even made critical remarks on John Woodbridge’s sermons. However, by Sunday, November 2nd she had made a firm decision about her affiliation:

“Since I wrote last, Theophilus has recovered – and I have been to Boston… heard Dr Channing preach – Doctor Harris, and Mr Gannet… Last evening Mr Hall came here on his way to Leverett in an exchange with Mr. H[untington] – he conversed with our children respecting their admission to the church; and Bethia and Whiting concluded to make a profession of their faith in Christ the first Sabbath in December – As I am dismissed [NB] from the church in Hadley – I have concluded to unite with the church in Northampton at the same time.”

Although the preaching of illustrious Unitarians, William Ellery Channing and Ezra Stiles Gannett, colleagues at the Federal Street Church in Boston, and Thaddeus Mason Harris of Dorcester, must have inspired her, the decisions by her daughter Bethia, age 23, and John Whiting, age 19, to make their professions at the Unitarian church in Northampton on Sunday, 7 December, seem to have been decisive. She explained her decision more fully the week after the service in Northampton:

“Last Sabbath Whiting, Bethia, Frederic [Dan, age 9] and I attended meeting at Northampton, the two first and myself were admitted to the communion. As I had been dismissed [NB bis] from the church in Hadley, I tho’t it best to unite there, tho’ I do not agree in every particular with Mr Hall. Yet, as he requires no particular creed, and as he seems to be a serious, conscientious man, I hope it may be acceptable to my Maker to follow this course. At the Lord’s table I had, I hope, some feeling of gratitude that I had such an opportunity of witnessing the desire of these children to honor God and their Saviour.”

Clearly the desire to be united with her children in the sacrament overcame any doubts regarding the wisdom of joining a church at odds with that of her youth and even regarding the young Unitarian pastor, Edward Brooks Hall, a recent graduate of Harvard (1820) and its Divinity School (1824), about whose theology she obviously had some reservations. Through all of this, there is no mention of her husband’s influence. It is unlikely that they did not discuss these matters, but her decisions throughout were evidently her own.

Dan did not join the Northampton church, and, as an independent “evangelist”, his affiliation with the American Unitarian Association, established in 1825, was ambiguous. In 1835 he tried once again to gain “occasional communion” with the Hadley church now under a new pastor but was once again refused. Betsey had no interest in joining this failed effort and was clearly more concerned about the religious affiliations of her children. During the years of her enforced alienation from the beloved church of her youth, she had developed her own Unitarian religious understanding which was evident in her spirited and independent response to the excommunication proceedings in 1828 and more persistent than Dan’s who finally joined the Russell Congregational Church in Hadley in 1859.

Dan’s prominent defiance and demonstrative independence of orthodox authority had forced Betsey to take a new religious direction, but she was adamant in her loyalty to her new church home which she called her “refuge” and her “mother’s bosom”. Her personal piety remained intense. Annually, in early April she entered a remembrance of her religious profession in Hadley at age nineteen which was marked by a Fast Day and meditations on the state of her soul. In his tribute to his wife’s piety, Dan noted that “by a very striking coincidence, her death took place on one of those anniversaries; her spirit left her body, at sunset, on the evening of April 6th, 1847.” Betsey, however, may have regarded it as a divine providence rather than a coincidence.

At the conclusion of his obviously-sincere and sorrowful tribute to his wife, Dan consoled himself that “she who has been the persecuted sufferer here [on earth] has taken her place among the martyrs in glory [in heaven]”. One can only wonder whether there is also a note of self-reproach. Dan realized that “although we were both equally vulnerable as heretics, [we] were not both equally at the disposal of the Church in Hadley. She was a member; I was not.” This consideration obviously had not tempered his marked inclination for confrontation with church authorities. “Equally vulnerable as heretics”, perhaps, but “equally” offensive to the church, probably not.